Know What Your Doctors Know: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

This video was originally published by National Comprehensive Cancer Network on December 17, 2018, here.

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in men and women. About 14% of all new cancers are lung cancers.

The two main types of lung cancer are non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. The types are based on the way the cells look under a microscope. Non-small cell lung cancer is much more common than small cell lung cancer

More resources for Lung Cancer from Patient Empowerment Network.

This video was originally published by National Comprehensive Cancer Network on December 17, 2018, here.

Clinical Trial Mythbusters: Is It Difficult to Participate in a Clinical Trial? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

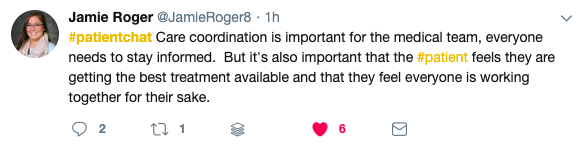

Three experts discuss the clinical trial process and the difficulty in participating in a trial. Our expert panel includes:

Andrew Schorr:

And greetings from Southern California. I’m Andrew Schorr from Patient Power. And welcome to this Patient Empowerment Network program, another in our series of Clinical Trials MythBusters. Our goal, of course, is to help you get the treatment for you or a loved one that you need and deserve. I want to thank the financial supporters for this program to the Patient Empowerment Network; AbbVie, Inc., Celgene Corporation. Daiichi Sankyo and Novartis for their support. They have no editorial control and we’re going to have a very freewheeling discussion today. And really what it’s about is how can a clinical trial be made easier for you to participate? Are there barriers? We’ve talked about it in previous programs. But specifically, what are the companies—the pharmaceutical industry mostly, who sponsor trials all around the world, what are they doing to make trial participation easier? For you to know about trials. For the people at your clinic to know about it and what to say and how to administer it. For you to have documents that are understandable for you and your family to know whether you want to participate. To keep you informed. And also related to the requirements of trials. How can they be relaxed a little so that there may be a trial that would benefit you, that you and your doctor agree on, and the requirements of it allow you to be in the trial. Okay, and the logistics of it are not so tough either. All right, I’ve been in two clinical trials, and I believe I’m alive today because of that. So, I’m very grateful. We have some wonderful panelists with us over the next hour. Now as you have questions, send them to questions@patientpower.info. And some of you have. So, you’ll be able to interact with us as we go along. First, I want to go to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, and T.J Sharpe. And T.J. has been on programs with me over the years. Stage four melanoma patient having been in trials. And T. J., you would agree, you’re alive today because you were in trials, right?

T.J. Sharpe:

Absolutely, Andrew. I think both of us are very fortunate that we found a trial that was the right treatment for us and gave us the ability to combat our disease in areas may not have been available to us if we just waited for standard of care therapies.

Andrew Schorr:

Right. And here you are—we should say that you were diagnosed a number of years ago with melanoma, went through trials. And now you’ve had two years without treatment, right?

T.J. Sharpe:

Yes. It’s been five years of treatment followed by now two good years of a clean bill of health.

Andrew Schorr:

Well, great. And I should mention for our audience, many people are familiar with T.J. T.J. goes around the country, gives speeches. He’s been at many events, consults with industry that are developing trials to try to bring the patient perspective forward. So, T.J., thank you for all you do. We really appreciate it.

T.J. Sharpe:

You’re welcome. It’s my honor to be able to represent all these patients.

Andrew Schorr:

Well, most every family—certainly most have been touched by cancer. But our other guests are not cancer patients but are in national leadership programs. And so, let’s go up to Medford, Massachusetts at Tufts University outside Boston, Ken Getz. Ken, welcome to the program. Ken, ladies and gentlemen, is a true national leader when it comes to clinical trials and really helping us move forward with better processes, better understanding. Ken, tell us a little bit about your organization there, CISCRP. What does that stand for?

Ken Getz:

Thank you. And I have to say your pronunciation was nearly perfect. It’s hard to pronounce it. It’s an acronym and it stands for The Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation. It’s a non-profit organization. It was founded 18 years ago. And it’s really there to help patients and their families navigate the whole clinical research progress which for many is completely unfamiliar terrain until they’ve been diagnosed with an illness or when they have exhausted all other treatment options. So, CISCRP really helps people become more educated and informed so that they can really think of the clinical research process with more confidence. And they can navigate this unknown terrain.

Andrew Schorr:

All right. I’m going to come back to you in a minute because you have such an overview, and you’re also an Associate Professor at Tufts. And so, you study all this, and you’ve written books. But I want to introduce the third guest. And that is a leader from the pharmaceutical industry and one of our most respected and venerable companies in the field, and this is Merck. So, joining us in a senior vice president of clinical operations there around the world. And that’s Andy Lee. Andy, welcome. Thank you so much for being with us.

Andy Lee:

Andrew, thank you. And pleasure to be with some prestigious panelists, both of whom I know. And I’ve met you over the last two weeks. And thank you to T.J. and yourself who have been trial participants and who are representing that part of the organization.

Andrew Schorr:

Okay, and we should mention that both T.J. and Andy are working on a couple of levels. And Ken sounds off on this too. There is a group called TransCelerate where pharmaceutical industry is working together on some of the issues they face in having the proliferation of trials. More trials sites, more accessibility, procedures for that. And then, of course, Andy has helped lead that effort at Merck related to breakthrough therapies that they have been trying to develop there in supporting patients who might be in Merck trials. So, we are going to come back to that. But I want to go to you for a second, Ken. Ken, how low is the participation among adults in clinical trials, at least in the U.S. Now, I’ve heard really low percentages. Where are we now with that?

Ken Getz:

Right, it’s a great myth for us to start with, this notion that only three to five percent of patients—eligible patients, participate in clinical research. That’s actually a statistic that was published by the National Cancer Institute in the early 1990’s. The latest research really shows that it varies widely. For example, when we look at pediatric cancers, the participation rates are extremely high, 80 to 90 percent in same cases—pediatric leukemia. In part because those communities have very engaged healthcare providers, very engaged families that really share their information. It’s just an enabled community where all of the stakeholders support participation. And then there are other areas of course. Some cancers where we do see relatively low participation rates. But I want to point out that low participation is driven by so many factors, Andy, including the strict eligibility criteria. And the demanding protocol designs which are a real burden for some people, and they choose not to participate. As well as low awareness, very low accessibility to trials among minorities and underserved communities. So, there are many factors that contribute to this variation in the participation rates.

Andrew Schorr:

Yeah, you’ve ticked off some now. T.J., in your own experience, one of the breakthrough trials you were in you had to go from Ft. Lauderdale in South Florida and move your whole family to Tampa in central Florida, right. I mean that was a big deal.

T.J. Sharpe:

Absolutely. When you have a young family and a stage four cancer diagnosis, relocating simply across the state during the holidays especially, is no big deal. We were fortunate because we had the means to be able to move there with work situation, with family. But too many people can barely go across the county, much less the state or the country to find a trial that might be the best match for them.

Andrew Schorr:

Andy, so we’ve ticked off some of the obstacles, and Ken touched on some about even the proliferation of trials. Is that a lot of what you do is how can we have trials be more accessible, be more widely distributed to a clinic near you?

Andy Lee:

Yes, let me just explain. When we look at a new cancer therapy, we look at the various cancers that may be affected. And what we do is we go for high probabilities of success. And the challenge is if you bring a new cancer agent. You normally start off in very advanced disease. So, patients would have failed multiple lines of therapy, and often it is a last gasp. And you have to show some sort of clinical efficacy. And then you move sort of backwards in the disease, and you go from sort of third-plus line, second line and first line.

And then you may work downwards into earlier stages of the disease into an adjuvant setting and maybe a neoadjuvant setting. So, as we sit down and design a trial, what we need to look at is what is the population that is most likely to show any benefit at all. And quite often when you are developing a new therapy, it’s difficult to show benefit because many of the patients are very ill. So, what we have to do is optimize the opportunity for success of a compound by going to the right target patients.

And quite often as we have learned a lot more about cancer, this does not mean we test a product broadly in anyone with cancer. We typically try and find a profile of a patient that is likely to respond. And many patients now will realize their predictor biomarkers or prognostic biomarkers. So, for example, with immunotherapies, those that work through the PD1 mechanism would probably want to have a PD1 ligand receptor positive patient who is likely to bind to the drug.

And that gives a higher probability of success. So, it sounds counterintuitive that while we want to develop therapies for all cancer patients, when we start clinical trial development, we have to show efficacy in a population that will benefit. And that’s normally predefined and makes the inclusion criteria fairly strict. As we show efficacy and as we can move into broader populations, it makes it a lot easier for us to design more liberal clinical trials. And then we can actually spread those in the geographic domains.

I could talk more about geographic allocation, but let’s hold that for the time being, and let’s see if there’s time later on.

Ken Getz:

Can I just add to what Andy said because I think it’s really important for your viewers to understand just how active drug development activity is today. We’re looking at over 4,000 pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, some of them very, very small. But in total, we’re looking at nearly 6,000 drugs that are in active clinical trials. And to Andy’s point, many are really targeting a patient with a very specific genetic profile or a specific biomarker. But it should give anyone who believes that a clinical trial may be an important care option for them, they should recognize that there may be many, many trials out there.

In total we estimate as many as 80,000 clinical trials, nearly 50 just conducted in the U.S. alone—50,000. So, it’s just important that we keep all this activity in perspective.

Andrew Schorr:

Right. So, T.J., that’s why all of us as patients need to ask about them, right? Go to different resources, whether it’s an advocacy group that you ultimately spoke with other patients, and obviously quizzing the doctors we go to. Is there something that may line up with my situation, right T.J.?

T.J. Sharpe:

Absolutely. There is a both top down and bottom up approach here that patients as they become educated—and every patient should be the owner of their healthcare as they become educated. Hopefully they are coming across advocacy organizations, other informed patients, patient support groups—all of which will help inform them different options for disease treatment, including hopefully as Ken mentioned, clinical research as a care option. At the same time, there is certainly very much an opportunity from the top down from the sponsors who develop the trials and from the sites that execute them to educate patients as they come in.

Not just at their own site, but at any site, at any medical facility. That if you have a diagnosis and you are looking into your care options, that you should be asking the question. And we should be giving you more information on the possibility of clinical trials and where you may find clinical trials that are appropriate for you.

Andrew Schorr:

Right, the whole enchilada, if you will, of all your options. Andy, so you mentioned about trial requirements. So, first of all, what efforts either at Merck or are you aware in the industry are being made to really talk to patients early on as you are designing trials? Whether it’s the requirements—how many CT scans you’re going to have. How often you are going to have to go to the main trial site. All the different things that sometimes get in the way.

Andy Lee:

Well, firstly we start with design. And we believe in exquisite trial design, quality by design as well. So, what we want is to run the experiment once and not have a sloppy trial design. We want to make it really robust in terms of scientific integrity and operational execution. So, we have a lot of internal design committees and what we do is we co-op with many groups external to our company. So, we speak to people who run clinical trials at cancer institutes.

We speak to the doctors who manage this. We speak to the trial coordinators. We speak to people involved with the transporting and shipping of medicine how they would do that. And then we of course speak to people in the ecosystem. We quite often speak to investigational review boards before we start trials. We talk to them about our design and what would be best to protect the rights and well-being of patients. And then, of course, the patient-centric approach says that we need patient insights.

And I’ve chosen my words very carefully because the insights are really important. Not all patients—and I’m very respectful that some patients are very intelligent and actually may be involved in this. Some patients can contribute to design, not all can. And so, what we do is we take the insights and we impute those. We often have focus groups. We talk about this disease. We talk about the burden of the disease. And then we talk about how that disease is managed in an ecosystem. And quite often in different countries it’s managed differently.

And so, we have to appreciate the global clinical trials have to navigate a path that may not be a linear path as we’d see it at an exquisite elite cancer center in the United States. It’s community-based, it’s all the rest. So, we take that input, and what we try to do is unburden the trial for the patient. We say, “How can we design a trial that requires the least visits to the clinic—the hospital, the least burden for them. And how can we take some of that burden from the clinic and actually transfer that into an easier environment.

So, document reading and review. Perhaps filling in questionnaires about quality of life. These are things that don’t have to be done in the clinic itself. And then often when we work with clinics, we work with them to help them understand how we as sponsors can make their life easier. And some of those things might be simplifying the informed consent. But I want to stress just one point here is that we can do whatever we like in the design at a company.

One of the things is, the patients are not sponsor patients. Okay, we sponsor clinical trials. The patients are managed by a doctor and a professional. And underneath that principal investigator is a whole oncology team. And it involves radiology. It involves pharmacists. It revolves around a 360 multidisciplinary team. They’re exquisite. They help manage the patient, not the sponsor. We provide the enabling functions for them. And then also that the oversight of the patient’s right, safety and wellbeing is the responsibility of an institutional review board.

And while we may provide templates and simplify templates in text and language, we rely heavily on the institutional review boards to help us with things that may make things easier, such as reimbursement for parking, transport, all of these things. And by and large, the institutional review boards are very supportive of these things. But they are very difficult to quantify in exact terms because of different geographic regions and different norms in different places. So, we rely heavily on exquisitely well-trained 360 team who manages oncology patients with a great PI. They manage patients.

And we work collaboratively with the sites who work with patients on our behalf. So, I just wanted to say the myth is that sponsors interactive with patients. That’s a myth. And the truth is that we engage with clinical sites, and we try and make our design and all the elements—the enabling elements, simpler for the trial sites in order to manage the patients in a simpler way.

Andrew Schorr:

Okay. Thank you for that. So, Ken, I want your comment on that. Because okay, we are downstream patients. We have a doctor, healthcare team. And we know somewhere in the background there’s a sponsor that tried to enable good things to happen to get reliable data and hopefully a cure for us. So, how do we—what’s happening? Are we improving things there in that interaction between clinic and patient?

Ken Getz:

Yes, we absolutely are. And I’ll start by just echoing and acknowledging that Andy has really laid out just an incredible amount of input that goes into the design of a protocol. And that’s really for a really large company. We see many, many examples now of patient advocacy groups or smaller companies turning to a variety of approaches to solicit input from patients and healthcare providers. Some virtual approaches through a social media or digital community. So, there’s lots of ways that feedback is being channeled.

And that’s really important. The flip side, to really answer your question, is that our protocol designs are becoming more and more complex, more and more demanding. A much larger proportion of drugs are now targeting rare diseases that have been stricter inclusion and exclusion criteria. And the designs of the studies—the number of procedures and the number of visits. The number of investigators that are involved, all of that has also continued to grow. And as a result, we do see that our trials are taking longer.

We have yet to see a year when we actually witnessed a reduction in the cycle time to conduct a clinical trial. And we just have to figure out new ways of making the participation process less burdensome and more efficient.

Andrew Schorr:

Oh, my. So, T.J., you had been living with stage four melanoma, a life-threatening condition. We have people even on our team who are living with stage four disease. So, when Ken talks about things slowing, that’s not what we want to hear. We want to hear two things. One is, we can accelerate a development of new medicine. And ideally—because this is an issue certainly in the U.S., but I think worldwide, that by speeding the process, cutting through red tape, improving procedures and us participating, the cost can be less as well.

And when we talk about cancer, the costs are going through the roof as you know for people living with chronic cancer. And you know so well, Andy, people who are on some of the medicines that you’ve come out with at Merck. Where people used to die unfortunately in short order, are living a much longer life thanks to new medicines. We want it to happen faster and be financially achievable. Andy, any comment about the pace of science?

Andy Lee:

Yeah, I would like to make a couple of comments about that. We often hear the sort of story that 80 percent of clinical trials don’t recruit on time, et cetera. We do immense feasibility. Once we have designed a protocol, we send it out to all of the countries that could potentially work with us. We have staff in 47 countries. And they look at two areas of interest. One is the medical durability, is the comparator the one we use in our country. Is the protocol designed the way we practice clinical medicine, not clinical research medicine?

And will that enable us to recruit the patients? That’s the first level. The second level we look at is to ask the question, is this operationally feasible? Can we source the comparator? Do the clinical sites have the equipment? How would we have to ship the biological samples around the world? And based on medical durability and the operational durability, we do a site selection. And we run the indicators through a Monte Carlo simulation. And we simulate this trial. What if we took three countries out? What if we added this more sites? What if we changed this inclusion?

And we come up with a model of what the recruitment would look like. And recruit about 80 percent of our trials according to our model. So, about 80 percent of our trials recruit on our model time. And then if we look at the typical time for drug development, it has been from eight to 10 years for many years in the industry. And when we look at some of the development timelines now—the cycle times. Pembrolizumab (Keytruda), for example, from first study until first approval, was 60 percent reduction in time.

We were looking in the four-year time period. And we are looking at five or six years for many indications. And so, we’ve halved that cycle time for some of the newer oncology products. And there are a number of reasons we’ve done that. One is we have found operational efficiencies. Two is the trial design has enabled us to interim analysis with independent data monitoring committees to assist with that. I’d also like to put in a positive plug for the regulators.

I do believe—and I’ll talk specifically about the FDA, because they are the agency for the United States. They have revolutionized the way they approach the designs and the way they review the data. And they have breakthrough designation status they’ll give to compounds that are really looking like they have strong efficacy. And so, the approval process through the agency has improved remarkably. And they’re open to adaptive designs. And they are open to interim analysis. And they are open to all sorts of things.

So, I really wanted to give credit to our agency who has said, “Where there’s a need for breakthrough medications, we’ll try to find the path.” And so, I do believe there’s a real positive side to this. The challenge is the market is saturated. We have now more than 25 PD1s in development. And to put the 25th one in there, they are so far behind in development. I wonder what that does. It clogs up the system. So, when you look at how can we influence sites, at the top sites we only get one or two patients.

And we compete with 50, 60, 70, 80 other sponsors. And so, it becomes so saturated that, that site has to learn to do systems and process with 70 companies. And what they are doing is almost hedging. They are not focusing on certain things. So, in those cancer centers, they offer treatment for all lines of therapy and all types of cancer, the specialized and nonspecialized. And we are moving out of that sort of geography and moving it community-based oncology practices where it’s less saturated, and we can actually have more traction there and be able to engage more with the clinical trial enterprise for the good of the patients.

Andrew Schorr:

Ken, you write books about all kinds of issues around this. So, if we are getting—particularly in oncology to have trials offered at the community practice where those doctors work night and day—the nurses. They are really stretched. More and more cancers, genomic subtypes, most sophisticated testing. How—what would you say the patient can do. T.J. talked about it a little bit. What would you recommend to patients so that at that community oncology practice the patient and the family can kind of discover what may be available for them as Merck and other companies try to get these trials distributed?

Ken Getz:

Right, well you—talk about the whole enchilada, Andrew. You’re really touching on it. It’s also very exciting times for patients, not just cancer patients, but patients that are dealing with any chronic and severe illness today. And it’s really all about more of a partnership with the clinical care environment and clinical research. And of course, at the heart of it is the patients and their family being as informed as possible, sharing their electronic health and medical information so that they can be connected to trials that might be appropriate for them.

But it’s moving—as Andy said, away from the classic places where trials used to be conducted. And in many cases, they were at these dedicated centers that only conducted clinical trials. It’s a very competitive environment now for patients. So, many sponsor companies like Merck and others are looking at clinical care settings and moving into communities or, in some cases, large health systems where you can have clinical research professionals who will supplement and provide support to the healthcare providers, so they’re not stretched too thin.

But so that they have the clinical research capability onsite at the point of care. For patients it’s a great opportunity because now they have the opportunity to get their own healthcare or treating physician and treating nurse involved in a clinical trial as part of their overall care. And we expect to see more of that over time. We expect to see other virtual trials or opportunities for patients to participate in the comfort of their own home tied in with their clinical care setting.

And all of this is relatively new to the whole world of clinical trials and the investigation of experimental medications.

Andrew Schorr:

You touched on something I just want to follow up on. I’ve heard of this term site-less trials where you said you participate in your home. So, T.J. had to go from Ft. Lauderdale to Tampa. I had to go from Seattle to Houston. There are not—this is a big deal, especially if you have little kids as I did, he has. So—and away from work and whatever your situation is. So, is technology going to come in play so Andy can get the data he needs for the FDA, but that we can have technology help accrue that data in a more efficient way.

Ken Getz:

And I’ll say absolutely. And my colleagues here today I’m sure can comment on this as well. But absolutely. We are seeing wearable technologies and mobile applications that now have the ability measure vital signs and other important baseline information in a validated manner. There are ways that you can access a specific facility for a highly specialized test, specialized imaging for example where the technician can evaluate it remotely. Blood can be drawn at remote locations as well.

So, there are lots of places where we have sort of this more flexible environment that can cater more to the patients and less about a specific physical facility where you have to go to participate in a trial.

Andrew Schorr:

T.J., I want to talk to you about diversity. So, you and I are kind of middle-class white guys. But we want to know how new medicines work for a variety of populations, ethnically, economic groups, et cetera. And Andy needs that data. And he goes to the FDA, and the FDA says, “Well, do you have Hispanic people? Do you have Asian people? Do you have African American people?” or whatever the country is because he works globally. And they say, “We want to understand are there differences?”

How are we doing with that. How can we make a difference there so that we really know what medicines make a difference for broader and also distinct populations?

T.J. Sharpe:

I’m sure Ken can back up some of these things with more hard data than I can. I know that different populations have different levels of trust with the medical system. One thing that you and I both experienced was a lack of options—a lack of good options. And when you get into dire straits, you tend to be a little more trustful of anything that comes along. But we have serious or chronic conditions that have proven treatments that might not be the most effective for certain populations.

And we’re not able to broad the scope to these minority populations or populations that don’t have access to NCI designated cancer centers or top-notch medical facilities. They are not able to get either in a trial that is looking for a drug that would help them or even get access to medicines that have been recently approved simply because their healthcare situation doesn’t allow it. Whether that’s a lack of insurance, a lack of healthcare literacy or simply a mistrust of—there’s a lot of generational mistrust I think in some communities of the clinical trial system.

So, as an advocate, I certainly push caretakers especially—and children caregivers for older populations who are maybe first or second-generation Americans to help facilitate a conversation between the medical professional who’s trusted and a patient that might not be able to get or rely on the information they’re given. Because it really will speak to populations that don’t get the opportunities that you and I have gotten simply because they are either not aware, or there is a barrier there to get to that medical professional.

Ken Getz:

I appreciate, T.J., you mentioned CISCRP. That’s one of the things that we’ve focused on for 18 years is bringing clinical research education into major metropolitan areas around the U.S. and parts of northern and western Europe where we plan for several months, and then we put on what we call an Aware for All events. And we really work very hard to encourage participation by—or from patients based within minority or underserved communities.

And I’m happy to say that we’ve had a lot of success with that. These are really difficult communities to reach through a lot of the traditional approaches. We have to rely on community centers and clergy and other approaches to really help these communities, for a lot of the reasons T.J. mentioned, trust the educational information, and come out to learn more. And I’m happy to say we’re seeing more and more people of diverse backgrounds that are curious and interested in learning more about clinical research, especially knowing that representative populations provide more information that can inform treatment for different types of patient sub-populations.

Andrew Schorr:

I want to go to Andy in a second. Andy, just one second. I wanted to mention and call out—and Andy’s company has been a leader in this. He was talking about PD1 and all of that. But drugs that have been breakthrough in immunotherapy for people like T.J. where—and it’s being explored in broader cancers where otherwise life was going to be short. And how to activate the immune system and really fight the cancer in people living long term. So, the people in those trials—and certainly there were people in the melanoma trials like yourself T.J.

Lung cancer trials and increasingly now others who did get tomorrow’s medicine today. Andy talked about accelerated approval which is great. So, that’s the impetus for the patient and the family. Is there the chance to get tomorrow’s medicine today? Now the obstacles may be distrust. You talked about that, Ken. And also, is maybe accessibility. Is it as a clinic near you? And Andy you talked about pushing that out. And then sometimes it’s related to cost.

Now is there anything that sponsors can do, Andy, related to the costs that people may have in being in certain trials? Where do we stand with that?

Andy Lee:

Yeah, so I’ll just touch on the distribution first and then get into the costs because they are linked. When we prosecute global trials—we’ve had a very U.S.-centric discussion so far. But cancers present differently in different geographic regions of the world. And so, when we want speed out of our trials. You want me to shorten that timeline and get drugs to market quickly. I do it internationally and in some cancers like esophageal cancer or some of the gastrointestinal cancers, Asia has a much higher prevalence of these cancers.

And we do a greater proportion of work there. We always include multi-country studies. And U.S. may have a greater proportion in other areas. So, we balance that out to optimize speed. Of course, with clinical trials the cost structure around the globe is very different. But let’s talk about U.S. We have spoken about a saturated core of clinical trial sites that we all go to. And I speak generally now for all sponsors. And we are all looking to optimize and get great efficiency.

At the same time, we realize we have many underrepresented geographies and ethnic groups—and not just ethnic groups, but under resourced populations. And so, what we’ve been thinking about is how can we support people, and support people at all levels. And so, we start off with thinking about the cost structure, and we obviously pay clinical sites for what they do. But we will support all sorts of things. We’ve been negotiating with Uber and Lyft, so we can build that into automated transport for patients.

Again, the IRB has to approve that. We are looking at ways to augment that they are not out-of-pocket for things. And we’ve been talking a lot with a group called Lazarex Foundation who has really expanded into under resourced communities and found ways to ensure that they have daycare and different access for those patients. We have worked extensively now to look at outreach programs into communities that typically wouldn’t be in trials. We are focusing in two areas right now as we speak.

One is next generation of HIV medicines, and the other one is in prostate cancer. And we’ve got a large program rolling out in prostate cancer. So, what we are doing is going into sites and we have put together training videos and training materials. And we are looking at cultural competency. So, it starts at the site. Are they culturally competent to engage a different community? And we’ve spoken about working with the community churches, community education systems.

And so that starts with cultural competency. I have a woman, Madelyn Goday, who works on this day and night in my organization. And she’s very strong at this. It’s early days, but if we can show that it works in one or two therapeutic areas and cancer types, we’d expand it further and further. But we can’t just have a shotgun approach and just go and do 100 sites and hope it works. Hope isn’t a good strategy. We are working systematically to engage different people. And as appropriate and approved by ethics committees, we will support all of these communities and help build infrastructure and capacity.

Those are important things for us. But as I said, where appropriate and where it’s sustainable. We can’t just throw money at something in the hopes something sticks. We have to have something sustainable and it goes to what Ken says, and that’s education and providing resources and materials. And we’ve used quite a lot of Ken’s materials in multiple clinical trials. Thank you for that, Ken. It’s been really helpful for us.

Andrew Schorr:

Great. I wanted to note for your audience. If you have a question, send it to questions@patientpower.info. We have expert panelists here. And this is really—we are all in this together. I think you hear the dedication from Andy at Merck and T.J. as a patient advocate and Ken as a professor and founder of organizations devoted to this. We want obviously accelerate medicines, but have the accurate data of how it affects different people, who is it right for so that the regulators—and thank you for what you said about the FDA here in the U.S., has the information to make a decision on should this medicine be available for people with that diagnosis.

Okay, so what about staying in the trial. So, T.J., how long—let’s take with the Keytruda trial or one of them. How long were you in to for?

T.J. Sharpe:

Nearly four years. Three-and-a-half years.

Andrew Schorr:

Were there ever times when you said, “I’m done. I want to bail out.” You know.

T.J. Sharpe:

I’ll be very careful how I answer this question for Andy’s sake.

Andy Lee:

It’s okay, T.J., we’re friends.

T.J. Sharpe:

No, probably the biggest crossroads I ever came to was when one of my tumors started growing about a year into it. And we weren’t sure if the medicine stopped working or not. We didn’t know what to do. And as it turned out, it was still working. And I think was just one spot that wasn’t responding. But everything else had responded great. However, at the point, as a patient, you’re thinking about yourself first and your family first and the trial second. It’s easy to stay compliant on a trial when things are going well.

But when you’re ahead of the medicine in some ways, and I think patients with chronic illnesses or in some cases rare diseases, are almost more knowledgeable than some of their doctors or the trial protocols about when they’re stopping. They don’t have the luxury of finishing out a protocol and seeing where their disease journey takes them. And the best example I can give of this is a very passionate advocate by the name of Jack Wheelen who we unfortunately lost a couple of years ago, but whose influence has kind of dominated the patient advocacy world for the last decade or so.

And Jack was able to monitor his health almost better than a doctor. And he knew when his trials weren’t working. When we get to that point in a clinical trial setting where we know the medicine is not being effective or where a patient would be better served to move on to another treatment. That’s when we are going to take the next step in clinical research, because now we’re aligning the trial design and the trial goals with a patient and a patient’s family’s treatment goals. And as those two points merge, that’s where clinical research becomes that much more effective as a care option.

Andrew Schorr:

That was well said. And I think with all those trials, you’re right, the team—that care team, what’s right for you at that time. Obviously to get the data, but also not at all costs. In other words, if the data is showing something is no longer effective for you, is there another treatment or a trial? I’ll just share my story for a second. So, I was in a phase two trial of combination therapies—which are increasingly common certainly in oncology. And after three months—halfway in the trial, my blood was kind of cleaned up.

And I had nausea and some other side effects. And I said to the trial coordinator, “You know, I think I’d like to stop.” And she said, “You know, our belief is that you still have microscopic illness in your bone marrow—in this case with the blood cancer, and the additional three months in this protocol will make a long-term difference for you. That’s what we believe.” They didn’t have the answer, but that’s what they believed. You know what? I stuck it out. She was right. I had 17-year remission.

If I’d stopped after three months, would I have? So, it’s a dialogue with the care team Andy, right? It’s this ongoing discussion not just entering the trial, but remaining in the trial, correct?

Andy Lee:

Yes. Absolutely. And I just wanted to impress a really important thing. People talk about people dropping out of trials. In cancer trials we see extremely low drop out. I mean these are potentially lifesaving medicines for all of the companies. But what we do want to make sure about is that when there is progression of disease, and it’s shown that the drug—whichever it is, the control arm or the active arm or the new agent, where there is progression of disease that they get the best available therapy.

And so that often contaminates trials because we have the crossover effect that now they are getting maybe the experimental agent in the standard of care type of thing. But most important thing for us is to track the survival of the patient, regardless of whether they go on another therapy. And we have put a tremendous amount of effort into looking at the informed consent and making sure we work with IRB to track patients long term survival.

Because as you’ve said, you may have a short-term issue that shows that the drug may not be working short term, but long term it may have prolonged and profound effects. Positive or negative, we don’t know that. And so, what we like to do is get long term survival. And we ask patients to consider when they sign the consent for whatever trial and whichever sponsor is sponsoring this, is to consider that knowing their status throughout their treatment—whether it’s on a sponsor’s drug or another sponsor’s drug or x therapy. It is really important — and I ask people to think about that.

Because that really helps us get as much data out of the individual treatment as possible. And that may prevent nonrequired trials in the future or it may say, “Wow, that really informed.” And we’d like to inform all cancer patients. If data we generate can inform other therapies, we certainly want to do that. We do not want to do wasteful clinical trials. So, tracking patients long term or patients—the message to patients is being cognizant of letting the sponsor—and the sponsor could be an institution. Letting them know your status is really important. All they want to know is are you dead or alive.

Andrew Schorr:

In the end, just one thing is, are we partners. In the end, our viewers here, are we your partner? And can we feel that not just for their doctor but you guys behind the scenes with the labs and everything, that in the end we are partners. And unless we see it that way, we won’t get anywhere.

Andy Lee:

Absolutely. I’m glad you used the term partners. Because when we’ve done a prep for this people have said, “Are they investors in the thing?” So, yes, patients invest their time and everything, but they are partners in research. They are contributing so much. They are contributing—they are going into the absolute unknown. And there is an immense trust level that is there. And we owe that back as research professionals is to treat people with respect, dignity and as partners, to make information available, to publish our data to get it out there as quickly as possible. And to make sure we get that back into the participant’s sort of hands.

Andrew Schorr:

So, Ken, how are we doing on that because you go back over the years and people say, “I don’t want to be in a trial because I’ll be a guinea pig,” and respect was not seen as part of it.

Ken Getz:

Well, that’s also a bit of a myth, right? You had a few that claimed that they felt the process made them feel like a guinea pig. The vast majority of people, over 90% of people who participate in a trial, would do it again. So, once they get past that unfamiliar area where they’ve perhaps only heard a few case examples or a few very vocal people who had bad experiences. Once they’ve done it themselves or they’ve been able to work with a group of advocates that really help them think about this process, and they become more educated, generally they’re very impressed with the level of professionalism, the compassion that exists at all levels.

I work with so many professionals—science professionals and pharmaceutical companies and at the research centers, and they all share that kind of commitment that Andy just mentioned. There’s a real desire to partner with the patient to really inform them. I would say one place where we need to see much, much more however is in the return of clinical trial results in a plain language to people who’ve been in trials. That’s a place where as an enterprise—government, research sponsors as well as industry have not really made this a standard practice at this point. And that’s one thing that we’re really working on actively.

Andrew Schorr:

Right. Great. So, T.J., you and I are investors—and Ken used that term and Andy used it, and I’ve always believed it. We are investors of our tissue, our body, our future to help other people and hopefully help ourselves. And certainly, for profit companies that may greatly benefit if they have a blockbuster therapy. But we need to be kept informed in the long term, right T.J.? We want to know what a difference our participation made.

T.J. Sharpe:

Certainly. And I think to echo what both Andy and Ken said is that patients do become partners. Patients who are involved in clinical research, a significant chunk become altruistically invested. I’ve heard more than once, “Even if this doesn’t help me, I’m glad I participated because it might help somebody else.” I know I’ve felt like that, and I’d venture that you’ve had some of that too, Andrew on your journey. So, it’s only—it’s at the very minimal fair, and it’s certainly very justified to expect as a co-participant in this.

And as kind of a co-creator of science with sites and sponsors that we understand what has come of our sacrifice and our time dedication to helping science out. We shouldn’t have to find it out through press releases from ASCO or hope that we hear about it on the nightly news. We deserve to hear what has happened. Not just because it can affect us as people and as patients, but that we put a lot into this too. And then we did our part to further medical research and we want to be part of the—whatever the end of the trial ends up being. We want to be aware of that. Not just for personal knowledge, but to know that it’s going to help this many other people.

Andrew Schorr:

Right, to be honored. So, Andy, at Merck you’ve established some internet platforms in particular related to keeping people informed, right?

Andy Lee:

Well, we’ve got an internet platform that people can log onto. I’m happy to share that with you; in which they can get access to a list of our trials. So, I didn’t prepare this but especially, but I did make a handmade note. And if anyone wants, it’s a very simple log on. Andrew Schorr:

You’re a great artist.

Andy Lee:

And it’s a simple one. What that will get you access to is two main important things. One is it gives access to information about clinical trials. We have a tab on there that tells everyone about the phases of clinical trials and what to expect in a trial. So, it’s an educational part. Then we have a lot of information about the Keytruda clinical trials were, are running, and they’re called keynote trials. And there you can look at the different indications. And you can look up and it has a telephone number you can call.

Now I must stress is that we run over 1,000 clinical trials in oncology. But many of them are not sponsored by us, they are investigator sponsored trials. So, you can go to clinics, and they run their own clinical trials that are not sponsor-related. And the NCI runs their clinical trials. So, there are a lot of different sources. And many companies will have clinical trials. We also have the website clinicaltrials.gov. I’ve had to use that in the last two days for a colleague.

And you can navigate that and look for different types of trials. And you can look at different products and everything. It’s not perfect. But at least it’s a place to go to. And I don’t want to sound as if I’m one sponsor centric. Many other companies have access to websites, and they really want to try and enhance and direct people to the clinical trials sites at which they are working.

Andrew Schorr:

Right, absolutely. And then you were working at the industry level with a group called TransCelerate, and I know T.J. is involved too, to try and establish common procedures as you establish trial sites, as you have communication, as you have training, right? So, that hopefully all boats will rise, right?

Andy Lee:

That’s correct. TransCelerate is a group that formed about eight or nine years ago. There were 10 initial member companies. I was a founder member of that. And we got together to say, “We have to improve operational efficiency.” So, we do not collaborate on molecular structures and those types—that’s competitive. We collaborate on what we call precompetitive, procompetitive aspects which says, “If we all work together to improve something, we’ll all get the benefit of this.” And we share it publicly.

There’s a website, you can look at it. But we’ve looked at standardizing protocols. We have a common protocol template. We’ve adopted that at our companies, so have other sponsors. The protocol can be developed in a standardized way. We’ve looked at standardizing ways where we can improve monitoring. We’re looking now at ways that we can work with investigative sites through i-platforms, shared investigative platforms. So, a clinical trial site has to provide the information for us as a sponsor and use the exact same standardized questionnaire and information for any other sponsor through a standard portal.

So, we are trying to reduce the burden on clinical trial sites. And we’ve plugged away for many years, and we are seeing greater traction there. We are seeing more efficiency, more standardization. We are seeing greater quality, less rework. And so, while it’s hard to quantify this, what we believe is that the sites are freed up of some of the more burdensome things, and they can direct their attention towards patients, patient safety, and access to clinical trials. So, the work may not be directly related to access for a cancer patient into a cancer trial, but there’s a lot of tangential spin-off of making a site more efficient so they can put their resources and energy in the right place.

Andrew Schorr:

Well, thank you for that effort and your leadership. So, Ken, you’ve been around this a long time. And you’ve deal with all the companies and the government and the various agencies. And as you know, in some quarters there’s a distrust for pharma. We mentioned cancer that you get the price tag of a drug, and it’s very expensive. And some people are struggling to pay for it. And there’s just frustration about it. And often in the news media they are the bad guys who are called out for unethical procedure or something that went awry.

So, how are we doing there in overcoming that because we talk to Andy, he seems very ethical, dedicated guy representing a company that’s been around I think well over 100 years. So, how are we doing to move clinical trials on in this area when people aren’t sure what to make of pharma.

Ken Getz:

Yeah. It’s a huge issue, Andrew. And I think part of the challenge is that all it takes is one questionable behavior, and it makes it difficult for the reputation of the entire industry. Right now, we are dealing with major pharma companies that are actually being fined for having contributed—a judgement, having contributed to the opioid crisis. And when you start looking at some companies aggressive marketing tactics, right? It really sort of sheds a darker light on a lot of the great work that companies do.

What we look at, at the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development at the School of Medicine. We look at the overall output, the level of innovation that’s coming from the industry today. And we look at the number of complaints that have been filed with the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world. And what we see is tremendous growth in the innovation and the quality of the innovation—drugs like Keytruda and other cancer immunotherapies. What an exciting area.

We see that the vast majority of companies really support and live by highly ethical, highly professional, highly compassionate approaches because they all know that it takes just one questionable issue that can really tarnish the reputation of every company operating in the industry. So—again, Andy also mentioned just how regulated we are as an industry, the fact that we have ethical review committees and data safety monitoring boards and so many other external agencies that help to oversee the work that’s done here.

So, I would say for patients who are thinking about clinical trials, it’s good to know the history. It’s good to know what you need to do to protect yourself. But the vast majority find that the people they deal with are ethical, they are professional, they are compassionate. And, as I mentioned, over 90% of people who get involved in trials say that they would do it again.

Andrew Schorr:

Thank you. That was a wonderful response. Andy, you mentioned earlier about starting research with the sickest people basically, where there are no options. But one of the questions that came in is, “Are trials only for the sickest people or are there of all those trials you talked about opportunities for people who maybe are newly diagnosed or could be their fairly initial therapy?

Andy Lee:

Yeah, great question. And thank you to the person who asked that. And the answer is that we start in people—because we don’t know if our experimental agent will work. And everyone assumes that new medicines are all going to succeed. And we work in research and researcher because of that many things fail very early on. They fail in phase one before anyone hears of it. It’s normally a code number at that point. And we may just not make the drug soluble enough, or it may not be distributed enough.

So, we may have a thing that works in a test tube or a petri dish. But to get that into humans and make sure that it’s safe at the dosage we use often fails. We just don’t progress far enough. So, what we want to make sure of is that firstly the drugs are safe. And there’s a trade-off between safety and efficacy. We’re constantly trading off. And so, what we do is we look at that and say when someone has no option and we want to get an option going, that’s where we start.

We’ve actually moved down the disease scale, and we’ve come into adjuvant treatment or secondary prevention. And we’ve gone into newer adjuvant is when you have a small tumor is we pre-treat to manage that tumor before surgery is done. And post-surgery we hope that there’s limited treatment or no treatment. And we actually have removed the cancer, and there would be no evidence of disease. But. of course, using the word cured is something we try not to do, because we prefer to use no evidence of disease.

But absolutely. And the next strategy is prevention of cancer. Our company does a lot of vaccinations in women’s health. We have a product that protects against human papilloma virus which is a precursor for cervical cancer. So, people who are vaccinated with this particular product—and I’m deliberately not using brand names for obvious reasons. But when you vaccinate for HPV, you essentially are preventing the likelihood of a cervical cancer. And there are now prospects in many disease areas where either vaccination or early treatment gives you a tremendous positive prognosis of not getting the disease later on in life.

The answer to your question is yes, we are absolutely looking at ways to prevent getting to a very advanced stage which is very costly to manage and very emotional and stressful and difficult.

Andrew Schorr:

I want to thank you. I just want to get a final comment on what you would say to patients or family member. And I want to start with you, Ken. What do you want patients right now to know so that—what tips would you give them so that they’d consider being part of clinical research or stay in clinical research and the benefit it could be for them.

Ken Getz:

I will say really two things. The first is there’s just a tremendous amount of information out there, and we recommend education before participation. So, do your homework and engage family and friends and people you meet and trust to help you make the decision. And the second point comes off of that. And that is this is not a decision you make alone. Really bring in your treating physician, your nurse. Bring in your support network. And chances are you will learn a lot, and you might even find a trial that is right for you.

Andrew Schorr:

Right. And Andy, what about you? A final point—what would you say to a friend or family member or colleague related to considering trials today.

Andy Lee:

We get this question every single day. And we get it from patients in need. And my answer is we are all patients. We are all going to face this as professionals in our job or professionals outside. And so, I say community of practice. And disease hits all of levels of society in all education professions, et cetera. And so, my thing is to encourage people to do what Ken has said. Work as a team. Get multiple inputs.

And I am sponsor agnostic. Get the best therapy that is available. And that may be the best care option—as I said, the ecosystem in which you get the care is really important as well as the medicines that you get. So, have the discussion. Trust the medical professionals, they are very skilled out there. They are extremely well educated. And I just urge people, “Don’t think on two clicks on Google you are going to solve what your treatment option is.” Really discuss it with people because not all the options are public, and there is not enough information available about how to manage the whole disease through the entire enterprise. Trust the professionals.

Andrew Schorr:

Well said. And T.J., you and I are alive today because of trials. What do you want—what’s the thing you want to leave our viewers with?

T.J. Sharpe:

That they don’t have to be involved in clinical research. I think that’s an important distinction to make. And it’s going to pull together what Andy and Ken said that clinical research should not be considered a hail mary or last gasp option. If you are a patient—and we are all going to be patients as Andy mentioned. You want the best care for you. You want to be able to weigh all of your options. And if you are not considering clinical research, if you don’t know about it or aren’t able to get the information you need about it, then you are not going to be able to make the best healthcare decision long term for your health.

So, take that information that you can get. Find the trusted sources. Be able to reach out to advocates or colleagues or someone that you know that would have the disease or can connect you with good information. And be your own advocate—a little cliché, but really own that healthcare information. And once you are able to collect all of the different treatment options, then you consult with your professional medical team as to what the plan forward—the best plan forward for your individual situation would be.

Andrew Schorr:

Right. T.J., my friend, thank you. It’s a delight to see you again. Andy, with Merck, thank you so much for being with us and bringing your years of expertise. And, Ken, being at an independent non-profit center and also at Tufts University there, thank you for all the work you do. I want to thank the Patient Empowerment Network for pulling this all together. And the sponsors who supported us in this effort, AbbVie Inc., Celgene Corporation. Daiichi Sankyo and Novartis.

All these companies and I’m sure many more, working so that research can move forward. We can be true partners in it. And hopefully get tomorrow’s medicine today to make a difference for the community and live a long life, and hopefully a cure, right? I’m Andrew Schorr in California. Remember, knowledge can be the best medicine of all.

Please remember the opinions expressed on Patient Empowerment Network (PEN) are not necessarily the views of our sponsors, contributors, partners or PEN. Our discussions are not a substitute for seeking medical advice or care from your own doctor. That’s how you’ll get care that’s most appropriate for you.

This podcast was originally publish on WE Have Cancer by on May 7, 2019 here.

Sasha Denisova – WE Have Cancer

Seeking out a 2nd and 3rd opinion in her cancer treatment resulted in a dramatic improvement in Sasha Denisova’s quality of life.

Sasha first appeared on this podcast in Episode 83 where she shared the struggle she faced getting doctors to take her colorectal cancer symptoms seriously.

During our latest conversation she discussed why she made the decision to forego treatment at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota to seek treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City. We also discussed:

This podcast was originally publish on NPR by John Henning Schumann, Mara Gordon, and Chloee Weiner on September 7, 2019 here.

Finding out you have a serious medical condition can leave you reeling. These strategies from medical and lay experts will help you be in control as you navigate our complex health care system and get the best possible care.

Here’s what to remember:

1. Your primary care doctor is the captain of your health care team.

With any serious diagnosis, there will usually be more specialists to see. Having a primary care doctor you trust helps coordinate the information flow and keep track of the big picture. Your primary is on her toes for possible medication interactions. Regular preventive measures shouldn’t be overlooked, either.

2. Don’t be afraid to get a second opinion.

If you’re offered treatment such as chemotherapy or surgery that can be life-altering, it’s crucial to get more than one opinion, ideally from a doctor working for a different institution. Oncologists and surgeons expect patients to seek second opinions — many provide them as a major part of their practice. If your doctor resents you seeking more opinions, that’s a red flag.

3. Get organized, stay organized, and find someone to help you if you can’t do it yourself.

Make a list of what you hope to accomplish at the doctor’s office. If for some reason you aren’t able to take notes, bring someone along who can act as an advocate and make sure your concerns aren’t overlooked. Ask for copies of your medical chart and test results so that you are part of the conversation — you have a legal right to see your records.

4. If you need a procedure, go to someone who does it all the time.

It’s true for medical care as it is in life: The more a doctor does a procedure, the better at it she’ll be. This means fewer complications and better outcomes. It’s OK to ask your doctor how many times she’s done a procedure; a high volume means competence when things go as planned, and calmness for unforeseen complications.

5. Use the Internet, but use it wisely.

Contrary to what you may think, your doctor wants you to be well-informed and engaged with your health. There’s more medical information available online than ever before, but a lot of it is garbage. Stick with trusted sources like the National Library of Medicine, PubMed.gov, or learn about and use the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

6. Figure out what matters to you, and fight for it

Our default setting for health care is that more testing is always good. But that’s often not the case, as tests have side effects and can cause undue anxiety because of false positives or incidental findings. Have a frank conversation with your doctor about your values and what you want (and don’t want!) and you’ll be an empowered patient with a doctor as your advocate, not your adversary.

This podcast was originally publish on WE Have Cancer by Lee on June 18, 2019 here.

Joe Bakhmoutski – WE Have Cancer

Joe Bakhmoutski was diagnosed with Testicular cancer in 2016.He founded Simplify Cancer to provide support and advice to those touched by cancer. During our conversation we discussed:

Simplify Cancer – http://simplifycancer.com/

Clinical Trial Mythbusters: How Does Medicare or Medicaid Impact My Ability to Participate in a Clinical Trial? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

Cancer patients are living longer as a result of clinical trials that test new treatments, therapies, procedures, or new ways of using known treatments.

Watch along as a panel of experts from the Diverse Cancer Communities Working Group (CWG) Sustainable Healthy Communities, LLC, Baptist Memorial Hospital–Memphis, and the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) explore the questions:

Laura Levaas:

Hello, and welcome to this Patient Empowerment Network Clinical Trial MythBusters program on a very, very important topic, what impact does Medicaid or Medicare have on a patient’s ability to participate in a clinical trial. My name is Laura Levaas, and I’m the lung cancer community manager for Patient Power. I’m also a Stage 4 lung cancer survivor. I’m two years out from diagnosis, and I’m also on Medicaid. So, this is a topic that’s really important to me on a personal level.

This program is produced by Patient Power. We want to thank the following companies who provided financial support to make this possible. While they don’t have editorial control, we appreciate the support of AbbVie Inc., Celgene Corporation, Daiichi Sankyo, and Novartis for their support.

Today we are joined by some really amazing guests, the first being Mark Fleury from the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network out of Washington DC, followed by Jeanne Regnante, also out of Washington DC, and Jeanne is with the Diverse Cancer Communities Working Group, Sustainable Healthy Communities, and last but not least, nurse navigator Laura McHugh from the Baptist Cancer Center in Memphis, Tennessee. Welcome to all of our guests today. Thank you for joining us.

So, Mark Fleury, Mark is interesting because he has an understanding, a very deep understanding, about this issue from a regulatory and research perspective. He’s going to share with us what he’s learned about barriers in clinical trial participation and solutions to overcome some of those options.

Jeanne is going to share her viewpoint as part of the Diverse Cancer Communities Working Group. She helps share information about access to care treatment and inclusion in clinical trials for underserved populations.

And Laura McHugh who is joining us by phone (she is a friend of a friend of mine, and she’s really amazing) is a nurse navigator who has worked in the cancer space for 24 years. And she helps guide people in underserved communities every day as part of her working life. She works with Medicare and Medicaid patients on the daily. So, we’re looking forward to hearing from her.

So, back to our program, patients are living longer as a result of clinical trials that test new treatments, therapies, and procedures, or new ways of using known treatments for new ways. The myth here behind Clinical Trial MythBusters today is that being in a clinical trial isn’t covered by medical insurance particularly for Medicaid or Medicare patients. I know for me personally I’m interested in being in a clinical trial and I’m on Medicaid but I don’t even know what that means. So, I definitely need some guidance.

So, as we’re talking about this today, if you have any questions about if you’re a patient yourself or you’re a support person for a patient that has cancer or any kind of disease wanting to know about clinical trials on Medicare or Medicaid, we’re here to help you. Send your questions to questions@patientpower.info. So, viewers who are joining us today thank you again. If you’re on Medicare or Medicaid, what do you even do if you’re presented with the option to participate in a clinical trial to treat your condition? Let’s talk with Mark Fleury. Hi Mark.

Mark Fleury:

Hello Laura. Thanks for having me on.

Laura Levaas:

Yeah. We’re so, so grateful to have you on our program today because you have such a deep knowledge in this industry and on this topic. Can you tell us real briefly what exactly you do for the Cancer Action Network? And then I’d like to talk to you about barriers around Medicare and Medicaid.

Mark Fleury:

Sure. So, I work for the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. We’re the policy and advocacy arm of the American Cancer Society, and we focus on public policy, so that’s regulation, laws that impact cancer patients. And specifically, my work deals with policies around research and drug and device development, so how can we get those findings that happen in the laboratory into the clinic. And specifically, that goes through clinical trials. So, I’ve spent the last couple of years with a large partnership of other stakeholders taking a really deep dive into looking at clinical trials and all of the challenges patients have in getting themselves enrolled as a part of those trials.

Laura Levaas:

Good. We look forward to hearing more. Can you tell us a little bit about the current state of clinical trial participation in the US right now?

Mark Fleury:

Sure. So, there’s not real solid numbers, but we believe somewhere between 6 to 7 percent of US cancer patients participate in a clinical trial right now. So, that’s a fairly low lumber overall, and it’s also a fairly low proportion of the patients who would be interested. Research has found that between 50 and 70 percent of patients would say yes to participating in a clinical trial if they were asked. But unfortunately, many are not asked. And some of those who are asked are unable to enroll for a variety of external reasons. One of the things that we do know is that the people who do enroll in clinical trials tend to be less diverse and better off financially than the overall population with cancer.

Laura Levaas:

Okay. What are some of the barriers around Medicare and Medicaid patients who want to get involved in a clinical trial?

Mark Fleury:

Sure. So, obviously, first of all, there has to be a clinical trial for the patient based on your clinical characteristics. But assuming that that is the case, for a patient to enroll in a clinical trial, it’s critical that their insurance cover the routine care costs of that clinical trial. In other words, there are costs in a clinical trial that a patient would see regardless if they were in a clinical trial not. Say, for example, the first step of any treatment is a surgery and then the second step in normal care would be one drug but in a clinical trial it’s a different drug.

Well, regardless, you’re always gonna get the surgery. It’s important that insurance cover that routine part of the clinical trial. And unfortunately, historically, that’s not always been the case. Fortunately, in Medicare, they have covered that since 2000. That is not the case universally for Medicaid. And we can talk a little bit more about that later if you’d like.

Laura Levaas:

Okay. Perfect. I would definitely like to follow up on that topic seeing as I’m a Medicaid person myself. Can you touch briefly on what actually is different between the two programs in terms of clinical trial, the actual coverage? You mentioned routine care; is that for both programs?

Mark Fleury:

Well, so what’s important to note is that Medicare is a federally administered program. And so, there is one universal federal policy, and if you’re in Medicare, it doesn’t matter if you’re in Florida or if you’re in Idaho, the policies are identical. Medicaid is an insurance program that while partially funded by federal dollars, it’s administered by each state. And as such, each state has quite different policies. So, if you’ve see one Medicare policy, it’s uniform. If you’ve seen one Medicaid policy, it’s only relevant in the state in which you happen to be. So, it could vary significantly from state to state.

Laura Levaas:

Right. And so, depending on your state, you would need to follow up with your local maybe human services office to get specific questions answered.

Mark Fleury:

That’s correct. Yeah. There are some resources (and I think we can provide those at the end of the webinar) where generally speaking some states have passed laws or signed agreements in which their Medicaid programs have to cover those routine care costs in Medicaid. And we can certainly make available those states. But even within those states, it’s important to look closely at the policies. For example, in Medicare, Medicare also covers any adverse events. So say, for example, while you’re being treated, you had to be admitted to an ICU for heaven forbid a heart attack or something like that. Medicare pays for all of those unexpected expenses. And that coverage may vary state by state in Medicaid.

Laura Levaas:

Okay. Thank you, Mark. We’re looking forward to those resources. And for those of you watching, we will definitely be providing a downloadable guide with all sorts of resources to help you. Thanks Mark.

Mark Fleury:

You’re welcome.

Laura Levaas:

Hi Jeanne.

Jeanne Regnante:

Hey Laura.

Laura Levaas:

Okay. I can’t wait to talk to you about this. I have so many questions. I feel like we could talk for an hour. So, aside from the myth, I came into this thinking, “I’m on Medicaid; I probably can’t get into a clinical trial when and if I get to that point.” And then also, “If I am, it’s probably cost prohibitive because I’m on a fixed income.” So, is participating in a clinical trial expensive or cost prohibitive if you’re on Medicare or Medicaid like I thought? I mean, I know Mark touched on some of the issues, but what would you say? How would you answer that?

Jeanne Regnante:

For low-income patients, the cost of routine care and logistic support needed during a clinical trial is certainly a barrier to participation. And Mark pointed out some of these costs. But specifically in patients in rural communities, remote communities, aging population, children, patients with cognitive disabilities or physical disabilities. These are the same patients who have low access to care in general.

And covering the cost for routine care in a clinical trial and also the logistic support is a clear barrier to participation. So, there are clear barriers there, travel, housing, parking, paying for food, on having access to clinical trials not only for routine care costs like Mark alluded to but also logistical support being included in the clinical trials. So, all of those things are barriers.

Laura Levaas:

And would you say that seniors are also part of this underserved population?

Jeanne Regnante:

Absolutely, especially seniors that live alone, that are in remote rural areas in the United States. And remember, that’s 20 percent of the population, aging population, in those areas. So, clearly, we need to do better to engage those patients in care and also clinical trials.

Laura Levaas:

So, is it possible for us to draw any conclusions about how many people are on Medicare or Medicaid right now in the US? I did a little bit of internet sleuthing mainly through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, and it seems like there – the numbers that I came up with were pretty high, and it’s almost like 40 percent of the population is on Medicare or Medicaid. And so, has it –

Jeanne Regnante:

That’s absolutely true. Look at by the numbers, there is 329 million people living in the United States, and that’s according to the last census, which is a hot topic these days. There is 60 million people on Medicare, beneficiaries, and about 66 million people Medicaid. So, together, that represents about 40 percent of the population. And we have to remember kids. So, there are 7 million patients on CHIP, which is part of the Medicaid program. So, if you include percentage of people on Medicaid plus kids on CHIP, that’s 22 percent of the population.

Laura Levaas:

So, then circling it back around to clinical trial participation, how can we connect the dots here?

Jeanne Regnante:

So, I think one of the main issues is clinical trial sponsors and the clinical trial operations folks in the sites working together to do a better job of reaching out to patients, ensuring that everybody is asked to participate, and not just selecting the ones who people think can participate but asking everybody to participate and understanding the eligibility of all patients and working together to help to cover their costs to keep them in chart.

Laura Levaas:

Got it. Mark, I’m gonna pull you back into the conversation here for a minute. Can you touch briefly on what’s happening in the news right now around Medicare and Medicaid that could potentially impact clinical trials? Or maybe, Jeanne, you can speak better to that.

Jeanne Regnante:

I’ll let Mark take that one.

Mark Fleury:

Certainly, so, Medicaid traditionally has been a program that has served primarily children in many states, children and pregnant women. Starting close to 10 years ago with the passing of the Affordable Care Act, states had the ability to expand Medicaid eligibility beyond those kids and pregnant women. And now we see many states who have expanded the roles of Medicaid recipients to healthy adults who just happen to be lower income.

And so, what that really has changed is the number of people obtaining their insurance through Medicaid. Obviously, there has been a lot of – it’s a state-by-state decision whether or not Medicaid is expanded. The Affordable Care Act as a whole is hanging in the balance in a court case, and there’s obviously been a lot of discussion about whether it should continue or not. So, certainly, the number of people who are supported through Medicaid is a dynamic number, and that certainly is subject to changing policies that are still under active discussion.

I will say that Medicare, again, the coverage for routine care costs in clinical trials for Medicare, long-standing policy since 2000 that has been relatively stable. And I would expect that to continue unchanged.

Laura Levaas: