Katherine Banwell:

Hello, and welcome. I’m Katherine Banwell, your host for today’s program. When faced with a cancer diagnosis, could a clinical trial be your best treatment option? Today, we’re going to learn all about clinical trial participation, what’s involved, and how you can work with your healthcare team to decide whether a trial is right for you.

Before we get into the discussion, please remember that this program is not a substitute for seeking medical advice. Please refer to your healthcare team about what might be best for you. All right let’s meet our guest today. Joining me is Dr. Pauline Funchain.

Dr. Funchain, welcome, would you please introduce yourself?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Sure. Thank you for the invitation. So, I’m Pauline Funchain, I am a medical oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic. My specialty is melanoma and skin cancers. I also lead our genomics program here at Taussig Cancer Center.

Katherine Banwell:

Excellent. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Thank you.

Katherine Banwell:

And here to share the patient perspective is Cindi, who is a colorectal cancer survivor. Cindi, we’re so pleased to have you with us today.

Cindi Terwoord:

Thank you, nice to be here.

Katherine Banwell:

Before we learn more about Cindi’s experience, I’d like to start with a basic question for you, Dr. Funchain. Why would a cancer patient consider participating in a clinical trial? What are the benefits?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

So, I mean, the number one benefit, I think, for everyone, including the cancer patient, is really clinical trials help us help the patient, and help us help future patients, really.

We learn more about what good practices are in the future, what better drugs there are for us, what better regimens there are for us, by doing these trials. And ideally, everyone would participate in a trial, but it’s a very personal decision, so we weigh all the risks and benefits. I think that is the main reason.

I think a couple of other good reasons to consider a trial would be the chance to see a drug that a person might not otherwise have access to. So, a lot of the drugs in clinical trials are brand new, or the way they’re sequenced are brand new. And so, this is a chance to be able to have a body, or a cancer, see something else that wouldn’t otherwise be available.

And I think the last thing – and this is sort of the thing we don’t talk about as much – but really, because clinical trials are designed to be as safe as possible, and because they are new procedures, there’s a lot of safety protocols that are involved with them, which means a lot of eyes are on somebody going through a clinical trial.

Which actually to me means a little bit sort of more love and care from a lot more people. It’s not that the standard of care – there’s plenty of love and care and plenty of people, but this doubles or triples the amount of eyes on a person going through a trial.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. When it comes to having a conversation with their doctor, how can a patient best weigh the risks and benefits to determine whether a trial is right for them?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Right. So, I think that’s a very personal decision, and that’s something that a person with cancer would be talking to their physician about very carefully to really understand what the risks are for them, what the benefits are for them. Because for everybody, risks and benefits are totally different. So, I think it’s really important to sort of understand the general concept. It’s a new drug, we don’t always know whether it will or will not work. And there tend to be more visits, just because people are under more surveillance in a trial.

So, sort of getting all the subtilties of what those risks and benefits are, I think, are really important.

Katherine Banwell:

Mm-hmm. What are some key questions that patients should ask?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Well, I think the first question that any patient should ask is, “Is there a trial for me?” I think that every patient needs to know is that an option. It isn’t an option for everyone. And if it is, I think it’s – everybody wants that Plan A, B, and C, right? You want to know what your Plan A, B, and C are. If one of them includes a trial, and what the order might be for the particular person, in terms of whether a trial is Plan A, B, or C.

Katherine Banwell:

Mm-hmm. Let’s learn more about Cindi’s story. Cindi, you were diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer, and decided to participate in a clinic trial. Can you tell us about what it was like when you were diagnosed?

Cindi Terwoord:

Yeah. That was in September of 2019, and I had had some problems; bloody diarrhea one evening, and then the next morning the same thing. So, I called my husband at work, I said, “Things aren’t looking right. I think I’d better go to the emergency room.”

And so, we went there, they took blood work – so I think they knew something was going on – and said, “We’re going to keep you for observation.” So, then I knew it must’ve been something bad. And so, two days later, then I had a colonoscopy, and that’s when they found the tumor, and so that was the beginning of my journey.

Katherine Banwell:

Mm-hmm. Had you had a colonoscopy before, or was that your first one?

Cindi Terwoord:

No, I had screenings, I would get screenings. I had heard a lot of bad things about colonoscopies, and complications and that, so I was always very leery of doing that. Shame on me. I go for my other screenings, but I didn’t like to do that one. I have those down pat now, I’m very good at those.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah, I’m sure you do. So, Cindi, what helped guide your decision to join a clinical trial?

Cindi Terwoord:

Well, I have a friend – it was very interesting.

He was probably one of the first people we told, because he had all sorts of cancer, and he was, I believe, one of the first patients in the nation to take part in this trial. It’s nivolumab (Opdivo), and he’s been on it for about seven years. And he had had various cancers would crop up, but it was keeping him alive.

And so, frankly, I didn’t know I was going to have the option of a trial, but he told me run straight to Cleveland Clinic, it’s one of the best hospitals. So, I took his advice. And the first day the doctor walked in, and then all these people walked in, and I’m like, “Why do I have so many people in here?” Not just a doctor and a nurse. There was like a whole – this is interesting.

And so, then they said, “Well, we have something to offer you. And we have this immunotherapy trial, and you would be one of the first patients to try this.”

Now, when they said first patient, I’m not quite sure if they meant the first colon cancer patient, I’m not sure. But they told me the name of it, and I said, “I’m in. I’m in.” Because I knew my friend had survived all these years, and I thought, “Well, I’ve gotten the worst diagnosis I can have, what do I have to lose?” So, I said, “I’m on board, I’m on board.”

Katherine Banwell:

Mm-hmm. Did you have any hesitations?

Cindi Terwoord:

Nope. No, I’m an optimistic person, and what they assured me was that I could drop out at any time, which I liked that option.

Because I go, “Well, if I’m not feeling well, and it’s not working, I’ll get out.” So, I liked that part of it. I also liked, as Dr. Funchain had said, you go in for more visits. And I like being closely monitored, I felt that was very good.

I’ve always kept very good track of my health. I get my records, I get my office notes from my doctor. I’m one of those people. I probably know the results of blood tests before the doctor does because I’m looking them up. So, I felt very confident in their care. They watched me like a hawk. I kept a diary because they were asking me so many questions.

Katherine Banwell:

Oh, good for you.

Cindi Terwoord:

I’m a transcriptionist, so I just typed out all my notes, and I’d hand it to them.

Katherine Banwell:

That’s a great idea.

Cindi Terwoord:

Here’s how I’m feeling, here’s…And I was very lucky I didn’t have many side effects.

Katherine Banwell:

In your conversations with your doctor, did you weigh the pros and cons about joining a trial? Or had you already made up your mind that yes, indeed, you were going for it?

Cindi Terwoord:

Yeah, I already said, “I’m in, I’m in.” Like I said, it had kept my friend alive for these many years, he’s still on it, and I had no hesitation whatsoever.

I wish more people – I wanted to get out there and talk to every patient in the waiting room and say, “Do it, do it.”

I mean, you can’t start chemotherapy then get in the trial. And if I ever hear of someone that has cancer, I ask them, “Well, were you given the option to get into a trial?” Well, and then some of them had started the chemo before they even thought of that.

Katherine Banwell:

Mm-hmm. So, how are you doing now, Cindi? How are you feeling?

Cindi Terwoord:

Good, good, I’m doing fantastic, thank goodness, and staying healthy. I’m big into herbal supplements, always was, so I keep those up, and I’m exercising. I’m pretty much back to normal –

Katherine Banwell:

Oh, good for you.

Cindi Terwoord:

– as far as my strength. I like to lift weights, and I run, so I’m pretty much back to normal.

Katherine Banwell:

Good for you. Thanks so much for sharing your story with us.

Cindi Terwoord:

You’re welcome.

Katherine Banwell:

Dr. Funchain, once a patient like Cindi decides to participate in a trial, what happens next?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

So, there is a lot, actually, that happens. So, there is a lead-in period to a trial. So, once you decide, it’s not like you can start tomorrow on a trial drug. What happens really, there’s a whole safety lead-in that we call an enrollment period, where there’s a long checklist of making sure that a person is healthy, and there’s nothing – no organ or anything in particular – where we would be worried about this particular drug.

So, there’s a check list, that way there are usually – sometimes there’s a new scan if the last scan is a little bit too old, just so that we know exactly what somebody looks like right when they walk into the trial and start the drug. There are usually some blood tests and procedures that come before, and some of the stuff – half of the blood is for the trial, and half of the blood is for scientist usually, so that they can work on some of the science behind what’s happening to someone on a trial, which is pretty cool.

And sometimes there is a procedure – a biopsy or something like that – that’s involved.

But in general, the lead-in is somewhere usually between two and four weeks from the time somebody decides they’re willing to be on a trial. And there are some extra safety measures, like if you hear about a trial, you can’t go on the trial right away, there’s got to be sort of a thinking period that’s usually about 24 hours before you can literally sign your name on the line.

But, yeah, I’d expect something about two to three weeks before going on a trial. And then once folks are on a trial, it’s kind of like treatment. It’s just getting the treatments when you get the treatments. Sometimes there’s extra checks, again for safety, on drug levels and things.

Katherine Banwell:

Would you review the safety protocols in place for clinical trials?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Yeah, sure. So, safety is number 1 when it comes to trials, really. There are guardrails on guardrails on guardrails. But in any clinical trial protocol, it actually starts even before the trial starts. So, whenever somebody wants to bring in a trial, or wants to start a trial – and this is true at any academic institution, or any institution that runs trials – the trial goes through something called an IRB, or an Institutional Review Board, and that board reviews it and says, “Look, is this safe, are we harming people, are we unnecessarily coercing people?”

And they read through the whole thing. And usually there’s a protocol data monitoring committee that also looks at it, there’s usually two. And there’s a lot of checks that a trial has to go through to make sure it’s safe, and fair, for all participants. So, that happens first.

And then once the trial opens, there is continual monitoring. Every visit, ever number that’s drawn. Any visit, even if the visit isn’t at the hospital that’s running the trial, even if it’s at a local urgent care, all of those things end up getting reported back, and there’s a whole team of people besides.

So, a patient will see the doc, or the nurse, or maybe sometimes a research coordinator, research assistant. But then there are all these research coordinators that sit in offices that review everything, put it in the computers, and then record everything that happens to someone on the trial.

And all of that data actually goes to an external review organization, a clinical trial research organization. And what they do is, they look over all of the data also. So, it’s not just internal people checking, because internal people may be biased for the people that pay them, right?

Katherine Banwell:

Right.

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

All of that data goes to an external monitoring board also, to make sure that everything is going the way it’s supposed to go.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. Cindi, in your experience, did you feel like safety was a priority?

Cindi Terwoord:

Oh, definitely, definitely, yeah. They were very, very careful. Mine was a two-part; I had a vaccine along with this nivolumab.

And so, they would have to give me the vaccine, sit there and stare at me, to make sure I didn’t faint or something, and that was a good half-hour.

Then I got the immunotherapy, and I’d have to wait an hour after that before I started on the chemotherapy.

Katherine Banwell:

Oh.

Cindi Terwoord:

Yeah, they were in there watching me like a hawk, and I felt very safe, I really did.

Katherine Banwell:

Dr. Funchain, what are a patient’s rights when they participate in a trial?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

So, the most important thing, I think, that Cindi mentioned before is, a patient can withdraw at any time. Any time. They can sign the paperwork, and the next second decide not to. They can be almost to the end of the trial and decide that they want to come off. The last word is always with the patient.

I think the other thing, in terms of safety, you can see – so every patient before starting a trial gets an informed consent. It is multiple pages, there’s a lot of legalees in it.

But they do try their best to make it as readable and understandable as possible, so that people can, even if they don’t have a medical background, kind of understand what they’ve gotten. The mechanism of what they’ve gotten, and what new drug they’re getting, and generally what are the risks and benefits.

For instance, let’s say there’s genetic testing involved, there’s always clauses that tell you what that means, and how protected your genetic information is, that kind of stuff.

So, it’s a very long thing. And again, once someone gets that, they have to have a certain amount of time before they can sign on the line. So, I think information education, and then the ability to come off if they find necessary.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. What happens after a trial is completed? Is a patient monitored? And if so, how?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

So, that depends on the trial.

Most trials do monitor after either the drug is complete, or the course is complete for a certain amount of time, and it depends on the trial. For some trials, it’s six months after; for some trials, it’s years afterwards. So, in melanoma, we have a trial that just reported out their 7-1/2-year follow-up. But it was actually the first immunotherapy combination of its kind that involved the drug that you had Cindi, nivolumab.

So, it is pretty cool. I mean, that combination changed the face of what patients with melanoma could come to expect from their treatment, so we’re all very interested to know what that kind of follow-up is. But, yeah, it depends on the trial.

Katherine Banwell:

Dr. Funchain, are there common clinical trial terms that patients should know?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

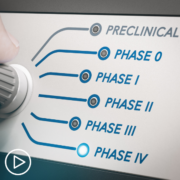

Yeah, there are trial terms that people hear all the time, and probably should know a little bit about. But I think the most common thing people will hear with trials are the type of trial it is, so Phase I, Phase II, Phase III. The important things to know about that are essentially, Phase I is it’s a brand-new drug, and all we’re trying to do is look for toxicity. Although we’ll always on the side be looking for efficacy for whether that drug actually works, we’re really looking to see if the drug is safe.

A Phase II trial is a trial where we’re starting to look at efficacy to some degree, and we are still looking at toxicity. And then in Phase III is, we totally understand the toxicity, and we are seeing promise, and what we really want to do is see if this should become a new standard. So, that would be the Phase I, II, and III.

Another couple of terms that people hear a lot about are eligibility criteria, or inclusion criteria. So, those are usually some set of 10 to 30 things that people can and can’t be. So, usually trials only allow certain types of cancer, and so that would be an inclusion criteria, but it will exclude other types of cancers. Most trials, unfortunately, exclude pregnant women. That would be an exclusion criteria.

So, these are things that, at the very beginning of a trial, will allow someone to enter, or say, “You’re not in the safe category, we should not put you on a trial.” Many trials are randomized, so people will hear this a lot. Randomization.

So, a lot of times, there is already a standard of care. When there’s already a standard of care, and you want to see if this drug is at least the same or better, then on that trial, there will be two different arms; a standard of care arm and experimental arm.

And then in order to be fair, a randomized trial is a flip of a coin. Based on a electronic flip of a coin – nobody gets to choose; not the doc, not the patient. On that type of trial, you’ll either get what you would normally get, standard of care, or something new. So, that’s a randomized trial. Not all trials are randomized, but some are. And those are the things that people will run into often.

Katherine Banwell:

So, if a patient is interested in joining a clinical trial, where should they start?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

They can start anywhere. There are many places to start. I think their oncologist is a really, really good place to start. I would say a oncologist, depending on their specialties, will have a general grasp of trials, or a really specific grasp of trials.

I would say that the folks who have the most specific grasp on trials– what is available, what isn’t available, what’s at their center versus the next state over center – are the academic medical centers; the ones that are sort of university centers, places like the Cleveland Clinic where the docs are specialized by the type of cancer. That group of folks will have the best grasp on what’s current, what’s available.

And so, Cindi, your friend referred you. many people do say that. Just go to whatever your nearest university center is, just because there’s a lot more specialization in that sense. But I think it’s the age of the internet, so people can look online. Clinicaltrials.gov is a fantastic place to look. It is not as up to date, I think, as something you can get directly from a person at a medical center, but it is a great place to start.

There are many advocacy groups and websites that will point people to trials. I mean, there are Facebook groups and things, where people will chat about trials. But I think the detail is better at a site like clinicaltrials.gov, and even better with a cancer-specific oncologist at a academic medical center.

Katherine Banwell:

If a trial is recommended, what questions should a patient ask about the trial itself?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

I mean, there’s so many questions to ask.

Katherine Banwell:

Safety is definitely one of them, right?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Yeah. I mean, I think when it comes to that, I think that the important things to ask, really, are what are the drugs involved, and what your doc thinks about those drugs.

I think, what is the alternative? So, again, we were talking about option A, B, and C. Is this option A of A, B, and C, or option C of A, B, and C? Are there ones like Cindi mentioned, where if you don’t do it at this point, you’re going to lose the opportunity, because you started on something else. Because a lot of trials require either that a person has never gone through therapy, and so this is sort of first line trial. But some trials are you have to be at the second thing that you’ve been on.

So, these are the things that matter to know. Are you going to lose an opportunity if you didn’t do it now, or can you do it later, and what is the preference? And I think, practically speaking, a patient really wants to know what is the schedule? Can I handle this? How far away do I live from the place that is giving this trial?

What are the locations available? Because if there’s a trial and you have to come in every two weeks, or come in four times in two weeks, and then once every month after that, that makes a big difference depending on where you live, what season it is, weather, that kind of stuff.

And I think the question that you don’t really have to ask, but a lot of people ask, is about cost. So, medical care nowadays is complex, it costs money when you don’t expect it to, it doesn’t cost money when it’s – you just don’t know what will and what won’t. Financial toxicity is something that we really care about. Every center is really trying its best, but it’s hard to do in this type of environment. So, people then get concerned that clinical trials might be even more complex.

I think clinical trials are much less complex in that way, because a lot more of it is covered by the sponsor, whatever that sponsor is, whether that sponsor is the National Institutes of Health, as a grant, or a pharmaceutical company.

But, in general, a clinical trial really should cost the same or less than whatever the standard medical care is; that’s the way they’re built. So, many, many people ask us that question, but I think that is the question that probably is less important than what are the drugs, what does your doc think about this, are you going to lose an opportunity if there’s a different sequence, and does this fit into your life and your schedule, and people who can give you rides.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah, right. Are there resources available to assist with the financial impact of a clinical trial?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

There are not specific resources for clinical trials; there are specific resources for patients in general, though. There are things like helping with utility bills sometimes, sometimes with rides, I think a lot of clinical trials do pay for things like parking. In general, many trials themselves have extra financial support in them. There was a trial I remember that paid for airfare and lodging, because there were only five centers in the country, and so we had people fly in, and the whole thing was covered.

It depends on the trial. But in terms of outside of trials, there are always patient advocacy groups and things like that, where certain things can get covered. But often, the types of things that get covered by those groups are the same things that get covered with normal medical care.

Katherine Banwell:

Okay. Before we wrap up the program, Cindi, what advice do you have for patients who may be considering participating in a trial?

Cindi Terwoord:

Do it. Like I said, I don’t see any downside to it. You want to get better as quickly as possible, and this could help accelerate your recovery. And everything Dr. Funchain mentioned, as far as – I really never brought up any questions about whether it would be covered.

And then somewhere along the line, one of the research people said, “Well, anything the trial research group needs done – like the blood draws – that’s not charged to your insurance.” So, that was nice, that was very encouraging, because I think everybody’s afraid your insurance is going to drop you or something.

And then the first day I was in there for treatment, a social worker came in, and they talked to you. “Do you need financial help? We also have art therapy, music therapy,” so that was very helpful. I mean, she came in and said, “I’m a social worker,” and I’m like, “Oh, okay. I didn’t know somebody was coming in here to talk to me.”

But, yeah, like I said, I’m a big advocate for it, because you hear so many positive outcomes from immunotherapy trials, and boy, I’d say if you’re a candidate, do it.

Katherine Banwell:

Dr. Funchain, do you have any final thoughts that you’d like to leave the audience with?

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

First, Cindi, I have to say thank you. I say thank you to every clinical trial participant, everybody who participates in the science. Because honestly, whether you give blood, or you try a new drug, I think people don’t understand how many other lives they touch when they do that.

It’s really incredible. Coming into clinic day in and day out, we get to see – I mean, really, even within a year or two years, there are people that we’ve seen on clinical trial that we’re now treating normally, standardly, insurance is paying for it, it’s all standard of care. And those are even the people we can see, and there are so many people we can’t see in other centers all over the world, and people who will go on after us, right?

So, it’s an amazing – I wouldn’t even consider most of the time that it’s a personal sacrifice. There are a couple more visits and things like that, but it is an incredible gift that people do, in terms of getting trials. And then for some of those trials, people have some amazing results.

And so, just the opportunity to have patients get an outcome that wouldn’t have existed without that trial, like Cindi, is incredible, incredible.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. Dr. Funchain and Cindi, thank you both so much for joining us today.

Cindi Terwoord:

You’re welcome, thanks for having me.

Dr. Pauline Funchain:

Thank you.

Katherine Banwell:

And thank you to all of our collaborators. To access tools to help you become a proactive patient, visit powerfulpatients.org. I’m Katherine Banwell, thanks for being with us today.