Thriving With AML: What You Should Know About Care and Treatment from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

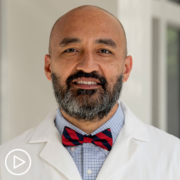

What should you consider when choosing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) care and treatment? Dr. Eytan Stein reviews factors that help guide care decisions for AML, discusses the goals of treatment as well as treatment options available, and shares tools for taking an active role in your care.

Dr. Eytan Stein is a hematologist oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and serves as Director of the Program for Drug Development in Leukemia in Division of Hematologic Malignancies. Learn more about Dr. Stein, here.

See More from Thrive AML

Related Resources:

Transcript:

Katherine Banwell:

Hello, and welcome. I’m Katherine Banwell, your host for today’s webinar. Today’s program is about how to live and thrive with AML. We’re going to discuss the goals of AML treatment and how you can play an active role in your care. Before we get into the discussion, please remember that this program is not a substitute for seeking medical advice. Please refer to your healthcare team about what might be best for you. Well, let’s meet our guest today. Joining us is Dr. Eytan Stein. Dr. Stein, welcome. Would you please introduce yourself?

Dr. Stein:

Thanks so much. My name is Eytan Stein. I work as an attending physician on the leukemia service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Katherine Banwell:

Excellent. Thank you so much for taking the time to join us today.

Dr. Stein:

Thank you for having me.

Katherine Banwell:

Since this webinar is part of Patient Empowerment Network’s Thrive series, I thought we could start by getting your opinion on what you think it means to thrive with AML.

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so thriving with AML I think can mean different things to different people. Thriving with AML can mean when you have the disease, really having the fortitude to get through the treatment that you’re being given because sometimes that can be tough.

And sometimes, it’s not easy. But the people who are thriving are the ones who are able to discuss with their doctors what their treatment is, what the side effects of that treatment might be, how to minimize those side effects, and how to get through that treatment so that not only do they feel better physically but can feel better emotionally and ultimately, hopefully go into a complete remission.

Katherine Banwell:

Thank you for that, Dr. Stein. I think that helps guide us as we continue this conversation. Getting appropriate AML care is part of thriving, and when we consider treatment options, it’s important to understand the goal of treatment. So, how would you define treatment goals for patients?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so the treatment goals for patients really come in different forms. I think fundamentally what everyone wants is everyone wants to go into a complete remission and be cured of their disease. And certainly, that’s an overarching goal that we aim to achieve with our treatments. But there are other goals that I think are important too to various patient populations, depending on what stage of life they’re in.

Are they 85 years old or 90 years old and have lived a long, full life? And their goal might be to improve their blood count so they don’t need transfusions so frequently. And they might be able to go to that grandchild or great-grandchild’s wedding or other life event. There are other patients for whom the goal might be, very discreetly, just to get to that next step in their treatment.

That next step in their treatment might be a bone marrow transplant. The next step in their treatment might be some more therapy. But I think overall as a doctor, our goal is always to do our best to get our patients into a complete remission and cure them while maintaining the best quality of life for our patients.

Katherine Banwell:

What do you think is the patient’s role in setting treatment goals?

Dr. Stein:

Well, it’s really important for the doctor to explore the goals of treatment when they first meet with the patient. I don’t think doctors should assume that all patients come into that first visit with the same goals. And what those goals are, I think, may differ a little bit from patient to patient. And it’s really important for the patient to express overtly what their goals are, what they want to achieve from the treatment. You know, I have some patients who come in to me and say, “My goal is to be cured and be alive for the next 30 years” or 40 years or 50 years.

And I have some patients that come into treatment, and they say, “You know what, I have had a very, very long life, and I just want the best quality I can have for as long as I can possibly have it.”

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah, that’s great advice. Thank you. As we move into the discussion about treatment for AML, let’s define a couple of terms that are often mentioned in AML care. What is induction therapy?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so induction chemotherapy refers really to a type of chemotherapy that tends to be quite intensive, so strong chemotherapy that patients receive in the hospital setting. That induction chemotherapy typically requires a hospitalization of three to four weeks, sometimes a little bit longer, as the patient gets their treatment during the first week or so and then they’re recovering from the effects of that treatment during the next three weeks in the hospital.

Katherine Banwell:

Okay. What is consolidation therapy?

Dr. Stein:

Ah. So, a patient first gets induction chemotherapy. If they achieve a complete remission, so their disease goes away, that’s great. We know their disease seems to be gone. But we also know that patients relapse. So, if patients relapse, it means their disease wasn’t really gone. It’s just that we couldn’t find it. It was hiding somewhere.

So, consolidation chemotherapy is chemotherapy that is given after a patient is in complete remission in an effort to kill any residual leukemia cells that may be hiding in the body, that we can’t see in our bone marrow biopsies, in an effort to deepen the remission that we’ve achieved during induction.

Katherine Banwell:

Okay. Are there any other terms that patients should be familiar with?

Dr. Stein:

There are. You know, there are a lot of other terms that patients should be familiar with. I’ll just touch on one because it can get complicated. We now have for acute myeloid leukemia, a type of therapy that goes beyond induction and consolidation called maintenance therapy.

Maintenance therapy is when a patient is done with induction, done with consolidation, and the question is, can you give them something that is easy to take, relatively non-toxic, that they can take for a prolonged period of time, to also help prevent relapse? Maintenance therapy has been really a backbone of the treatment of a different kind of leukemia called acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which happens primarily in children for many years. Maintenance therapy is also now a backbone of therapy for a different kind of blood cancer called multiple myeloma. And very recently, only within the past year to two years, we’ve incorporated maintenance therapy for AML for certain groups of patients.

Katherine Banwell:

Okay. What are the treatment types available to AML patients? You mentioned chemotherapy. What else is there?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so if I was having this discussion with you, even when I first started my career back in 2013, all I would’ve been talking to you about was induction chemotherapy and maybe a lower-dose chemotherapy called hypomethylating agents.

I think one thing that really needs to be recognized is that the advances we’ve made for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia, over the past 10 years, have been just remarkable. We’ve had a number up to nine drug approvals over the past 10 years, and those therapies fall into the following categories.

We now have therapies outside the strong induction consolidation we talked about. We have therapies such as targeted therapies that target specific gene mutations that are present in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Those are often oral therapies that patients can take at home. And we have very effective therapies for older patients who usually can’t handle the side effects of induction chemotherapy. That’s the combination of a type of drug called a hypomethylating agent with a very, very powerful targeted drug called a BCL-2 inhibitor.

One of those drugs, that drug is called venetoclax (Venclexta). That’s the one that’s FDA-approved. And the combination of those hypomethylating agents and venetoclax, has really changed the paradigm for how we treat older patients with acute myeloid leukemia, led to many patients who have been able to live much longer than they would have before this therapy came about.

You know, there are other therapies that are in development, but I don’t know if we’ll end up talking about that a little bit later. But there are therapies such as immunotherapy, which has gotten a lot of press for other kinds of cancers, like one cancer called the rectal cancer, that aren’t yet approved for acute myeloid leukemia but are being developed for acute myeloid.

So, the future of acute – the current treatments for acute myeloid leukemia are dramatically better than they were 10 years ago, and I would anticipate that we’re going to continue to see these kind of advances over the next 10 years.

Katherine Banwell:

And we are going to talk further about that in a couple of minutes. What about stem cell transplant? Who might be right for that? Who might be eligible?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so let’s go back to the discussion a little bit about consolidation chemotherapy. So, when you have a patient that gets induction chemotherapy or gets any therapy – it doesn’t have to be chemotherapy – to put their disease into remission, for a large group of patients, we think that the best way to cure their disease is to do something called a stem cell transplant.

So, what’s a stem cell transplant. What it is not is like a heart transplant or a liver transplant, which patients often don’t realize.

So, it’s not a procedure where an organ is being transplanted through a surgical procedure. What it is is it’s acknowledging that the cause of acute myeloid leukemia is that the most primitive cells in the bone marrow, called the stem cells, are the cause of the disease. And the chemotherapies that we give patients to get them into remission don’t always eradicate those bad stem cells.

So, what we’re able to do once a patient is in remission is we try to get them new stem cells. How do you get a patient new stem cells? Well, you go to a donor, and there’s a donor bank of people who have volunteered to donate stem cells to patients with acute myeloid leukemia. You go to the donor bank, and then you give chemotherapy to the patient to sort of wipe out their bad stem cells, and then you give them new stem cells that will hopefully permanently eradicate the disease.

What ends up happening is that a large group of patients with acute myeloid leukemia end up being referred for a stem cell transplant. The reason is twofold. You know, it used to be – I keep talking about the past. I’m getting older, and so now I can talk about the past.

Katherine Banwell:

We’ll talk about the future in a couple of minutes.

Dr. Stein:

Yeah. So, it used to be that stem cell transplants were really reserved to people less than 65 years old.

But our advances in our ability to do stem cell transplants has allowed for us to now successfully do stem cell transplants on patients, even into their upper 70s and sometimes even at the age of 80.

Katherine Banwell:

Wow, okay. That’s great. Where do clinical trials fit in to all of this?

Dr. Stein:

Ah. So, clinical trials are extraordinarily important for a variety of reasons. Clinical trials are important because the only way we make advances on a societal level in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia is by patients who are willing to participate in clinical trials. All of the – because these are trials that are testing new therapies with the goal of improving the survival and the quality of life of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. All these drugs I just talked about that have been approved over the past 10 years, they never would’ve been approved if patients hadn’t agreed to participate in clinical trials. So, that’s something that’s number one that’s very important.

But on a – forget the societal level for a second. On a patient-specific level, a clinical trial can potentially benefit a patient because it offers a patient access to a new, exciting therapy that may really help in improving their outcome of having acute myeloid leukemia.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. You mentioned emerging therapies. What are some of those?

Dr. Stein:

Oh, there’s so many. So, it’s hard to talk about all of them, but I think there are targeted therapies – I think if you sort of break them up into sort of broad buckets, there are new targeted therapies that are being developed for subsets of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. One of the ones I’ve been working on pretty heavily over the past few years is a kind of drug called a menin inhibitor. This is an oral medication that is given to patients of acute myeloid leukemia who have certain genetic abnormalities, specifically either a mutation in a gene called NPM1, or a what is called a rearrangement in a gene called MLL.

So, that’s a group of – that menin inhibition seems to be extraordinarily effective in treating patients, at least from the early data, for those specific subtypes of acute leukemia.

The other therapies that are really getting a lot of play now are the immunotherapies, which I mentioned a second ago. There are immunotherapies that work to – called bispecific immunotherapies where what happens is it works to harness the immune system to kill the cancer cells. You may have heard a lot about CAR T-cell therapy, which is another way of harnessing the immune system and engineering immune cells to target acute myeloid leukemia cells. And the other thing I want to point out is that even if you don’t have a new therapy against a new target, you can imagine now that we’ve got all these 10 new approved drugs.

But what we’re trying to figure out – one of the things we’re trying to figure out over the past few years has been what’s the best way to give these new drugs? What kind of combinations can you put them in that might make things even better? Maybe you should give two of those drugs first and then give another drug afterwards. And a lot of the research that’s being done now is being done to understand the best sequencing and combinations of drugs with the drugs that we already have approved.

Katherine Banwell:

Great. All patients are different, of course, and what might work for one person might not be appropriate for another. How do you choose which treatment is right for a patient?

Dr. Stein:

So, it’s an individualized decision. So, what you’re talking to the patient, as we talked about at the very beginning, is you really need to understand the patient’s goals for treatment. You need to understand the anticipated benefit of the treatment that you’re offering and need to understand the side effects of the treatment.

So, and that sort of becomes the puzzle that you work with the patient at putting together. That is how well do I expect this treatment to work? What are the potential side effects of the treatment, and what are the patient’s goals? And when you sort of lay all those different pieces out, you then usually come up with something that becomes pretty clear what the best thing to do is.

So, I’ll give you just a very concrete example of this. Sometimes, we have treatments where the medical data would suggest that they might work as well as one another, right? There’s no clear difference between each of the two treatments. But maybe one of the two treatments requires you to be in the hospital, and one of the treatments allows you to be at home.

So, that’s an important discussion to have with the patient because some patients, believe it or not, want to be in the hospital, because they’re worried about being at home and having to manage this all themselves. Some patients don’t want to be in the hospital. Some patients want to be at home, because they’re scared of the hospital, or they’re worried the food’s going to be terrible.

And then, that would be important in helping the patient make the decision for their treatment.

Katherine Banwell:

Right. You mentioned earlier, Dr. Stein, the difference in ages and how you would treat different people depending on their age. So, when you’re choosing a treatment, you obviously look at age. What else? Things like comorbidities?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so age, so I’m not ageist. So, it’s more that as people get older – and this is just a fact of life – as everyone gets older, their organs don’t work quite as well anymore, right? Things start breaking down as you get older. So, certain treatments aren’t appropriate for older people because the treatments a younger person, because their organs are working at 100 percent, may be able to handle it, while an older person, where their organs might only be working at 60, 70 percent, the treatment might not be as good of a choice for them.

So, that’s what I mean. So, as people age, their comorbidities increase. So, we always look at comorbidities, and if you had an 80-year-old that was running marathons, I might think about their treatment differently than an 80-year-old who is not running marathons. But most 80- and 85-year-olds aren’t running marathons, so that’s why we sometimes think about their treatment differently.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. Why is identification of genetic markers essential before choosing treatment?

Dr. Stein:

Because when you know the genetic markers, you can target the genetic abnormalities, sometimes with specific targeted therapies, with therapies that fit like a key in a specific lock. And those targeted therapies have been shown, in some cases, to improve the survival of the patients, without much cost, without much toxicity. So, I’ll give you an example of this.

There is a very common genetic abnormality in patients with acute myeloid leukemia called the FLT3 or FLT3 mutation. When you have that mutation, there is a targeted therapy that targets the FLT3 mutation called midostaurin, and it’s been shown in a very large clinical trial that the addition of the targeted FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin in combination with chemotherapy leads to better overall survival than chemotherapy alone.

So, you need to know that information because you want to give your patient the best chance at beating the disease. And that’s why it’s also important to try to get this information back quickly. You know, no one wants to be sitting around waiting for four weeks to find out if they’ve got a specific mutation. And we’ve gotten better. I think medical centers generally have gotten better at getting this mutational information back to their doctors relatively quickly.

Katherine Banwell:

Does every patient get this standard testing?

Dr. Stein:

It is – does everyone get it? I don’t know. But “Should everyone get it?” is, I think, the important question. Yes, everyone should get this testing.

It is incorporated into the NCCN and National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Leukemia Net guidelines. It is important not only because you can think about targeted therapies, but it is also important for prognostic reasons, meaning that certain mutations lead to a higher risk of relapse, and those mutations in a patient might lead me to recommend a stem cell transplant, which is sort of the most intensive thing we can do to help prevent a relapse, while other mutations, which might be “favorable”, in quotes, they might lead me not to recommend a stem cell transplant.

So, I think this mutational testing is the standard of care and should be done in every patient with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia.

Katherine Banwell:

Once treatment has begun, Dr. Stein, how do you know if it’s working?

Dr. Stein:

So, that’s a good question. So, the good thing about acute myeloid leukemia when it comes to understanding what’s going on, you know, it’s a disease of the bone marrow cells. And we do bone marrow biopsies to see how things are doing. But no one likes a bone marrow biopsy. It can be a somewhat uncomfortable procedure.

Katherine Banwell:

How often would a patient need to have a biopsy?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so they have bone marrow biopsies at diagnosis, and then they often will have bone marrow biopsies two weeks to a month later.

And then, if they’re in remission, basically any time you think if you want to check to see if they’re in remission or if you suspect the patient is relapsing. Then, you would do a bone marrow biopsy. But what I was getting at is that but you have blood. And the blood is kind of like the bellwether of what’s going on in the bone marrow.

So, the analogy I use for my patients is, you know, when you’re driving your car and you have – you know, you don’t open the hood every day to make sure the car is running okay. You know, you’re driving your car, and if your car starts making a funny clinking sound, that’s when you open the hood.

So, the blood is like the clinking sound. If you see something going wrong in the blood, that’s when you know you’ve gotta open the hood and look under the hood. If the car is running just fine and you don’t see anything wrong in the blood, using the analogy, maybe you don’t need to do a bone marrow biopsy.

Katherine Banwell:

What if a treatment isn’t working? What if it stops working or if the patient relapses? What do you do then?

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so when a patient relapses, which unfortunately happens more than we want it to, it’s important No. 1 to do another bone marrow biopsy and at that point, do that mutational testing again because the mutations that are present at the time of diagnosis are not necessarily going to be present at the time of relapse, and sometimes, a new mutation might occur at the time of relapse. And again, what that mutational profile shows can help determine what the next best treatment for the patient is. There might be standard-of-care therapies. More chemotherapy might be recommended.

When a patient relapses, I usually – excuse me – try to get them on a clinical trial because that’s the point where I think clinical trial drugs really have potentially major benefit for the patients, to help get them back into remission.

Katherine Banwell:

Why is it essential for patients to share any issues they may be having with their healthcare team, specifically, sharing their symptoms and side effects?

Dr. Stein:

Well, it’s important because we want to help you. I mean, I think that’s what it comes down to. All of us, whether it’s your doctor or your nurses or your nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant or anyone who is part of the healthcare system, we went into this business to help people. I mean, we knew what we were getting into when we went into this, and we want to help people. And one of the ways you help people is you help with their symptoms. So, if you’re not feeling well, you call up, and you say, “I’m not feeling well,” we can help you with that. You shouldn’t suffer in silence.

I sometimes have patients who will say to me, “Oh, I was going to call you, but I didn’t want to bother you.” You’re not bothering us. This is what – it’s not like you’re calling and asking for mortgage advice, right? This is what we do. So, it’s very important to call us because the other thing is that you’re going to be more – it’s more likely that you’ll be able to complete your treatment if we manage the side effects that you’re having rather than just ignoring them.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah, that’s great advice. With more oral therapies becoming available, patients now have a role in self-administering their treatment. So, what happens if a patient forgets to take a medication? Does that impact its effectiveness?

Dr. Stein:

The easy answer to that question is probably not. You know, if you forget to take a medication for three weeks, that’s not a good thing, but if there’s a – you know, this happens all the time, right?

You’re busy, and you just forget. If you forget to take a medication one night or one day, it almost certainly is not going to make a huge difference. Having said that, you shouldn’t see that as license to not be careful. So, it is important to try. So, set an alarm; put out a pill container do the kinds of things that can help you.

The other thing, there is a certain what I would call pill fatigue that sets in. Often, patients with AML are taking multiple medications at multiple times a day, and it can be hard. And at my center, we have pharmacists who do a lot of different things, but one of the things they can help with is sort of streamlining patients’ pill burden to make it easier for them to remember and to take the medications when they’re supposed to take them.

Katherine Banwell:

When a patient does forget to take a dose or even a couple of days’ doses, should they call their healthcare team and let them know?

Dr. Stein:

Yes, always call. Always call.

Katherine Banwell:

Okay. I want to make sure we get to some of the audience questions. These were sent to us in advance of the program. Let’s start with this one from Patrick. He writes, “Are there any clinical trials looking at maintenance therapy for the AML patients, especially older patients?”

Dr. Stein:

Yes, there are a number of clinical trials that are looking at maintenance therapy for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Some of those trials are maintenance therapies with targeted agents that are against specific mutations. Some of those trials are clinical trials with more broadly active agents that might be able to be used as maintenance therapy, so yes. Maintenance therapy is something that is really coming to the fore, and I would encourage you to seek out trials that might offer maintenance therapy.

Katherine Banwell:

Aaron sent in this question: “What are the most promising new effective drugs on the verge of being approved by the FDA, and what do they do?”

Dr. Stein:

Yeah, so I’ll just mention the one I mentioned a second ago, and that’s the class of drugs called menin inhibitors. I wouldn’t quite say they’re on the verge of being approved by the FDA, but I think that they’re very, very powerful drugs that within the next two or three years, they will likely be approved by the FDA if the early clinical trials continue to pan out. And those are drugs that at least in the early experience, seem to be specific for patients with these NPM1 mutations or these MLL rearrangements. And your doctor will know what those are if you ask them, “Do I have an NPM1 mutation, or do I have an MLL rearrangement?”

Katherine Banwell:

Thank you for that, Dr. Stein. And to our viewers, please continue to send in your questions to question@powerfulpatients.org, and we’ll work to get them answered on future programs.

What advice do you have for patients to help them feel confident in speaking up and becoming a partner in their own care?

Dr. Stein:

My advice is, speak up. You just speak up. It’s very important. It’s your – you know, at the end of the day, this is a disease that you are experiencing. Your doctor is there to partner with you and to guide you, but it’s your body. It’s your disease, and you need to be very vocal in what you’re experiencing and advocate for yourself.

Katherine Banwell:

If a patient has difficulty voicing their questions or concerns, are there members of the support staff who could help?

Dr. Stein:

Most centers have a social worker on staff that can help them out. I highly, highly encourage all of my patients to meet with a therapist or a psychologist that specializes in taking care of patients with cancer. I have become more vocal about this that I see. Really, it’s probably the best thing a patient can do for themselves, and there’s no downside. If you don’t like it, you don’t have to go back. Do one appointment and not go back. But that can be extremely helpful, extremely helpful.

So, it’s important in both ways. You need to alert your doctor that you might be feeling one way, but I think it’s also on the doctor to sort of take visual cues from the patient when they see them to understand what they might need and to make those kind of recommendations.

Katherine Banwell:

Yeah. As we close out our conversation, Dr. Stein, I wanted to get your take on the future of AML. What makes you hopeful?

Dr. Stein:

Oh, so many things make me hopeful. I mean, we understand this disease so much more than we understood it even 10 years ago. There are all sorts of new treatments that are being developed. We’re improving the survival of our patients with the new treatments that have already been approved over the past 10 years. And I really think the golden age of AML treatment is upon us, and I really think that – and some people might think I’m crazy – but I really think that by the time I’m done with this, you know, one day, I’ll get too old, and I’ll decide I need to go retire and spend time with my family. But I think by that time, we’re going to be curing the vast majority of our patients.

Katherine Banwell:

That’s so positive. It’s great to hear that there’s been so much advancement and that there’s so much hope out there for AML patients. I want to thank you so much for taking the time to join us today, Dr. Stein.

Dr. Stein:

Okay, thank you. It was really nice to be here.

Katherine Banwell:

And thank you to all of our collaborators. To learn more about AML and to access tools to help you become a proactive patient, visit powerfulpatients.org. I’m Katherine Banwell. Thanks for joining us today.