Tag Archive for: leukemia

Key CLL Treatment Decision-Making Factors

Key CLL Treatment Decision-Making Factors from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

What should a patient consider when deciding on a chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treatment approach? Dr. Susan O’Brien, a Hematology-Oncology specialist, provides key factors that help guide treatment choices for patients with CLL.

Dr. Susan O’Brien is the Associate Director for Clinical Science, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

|

|

Transcript:

Katherine:

Dr. O’Brien, once it’s determined that it’s time to move forward with treatment, what do you take into consideration to help guide the treatment choice?

Dr. Susan O’Brien:

Well, the good news and the bad news are kind of the same. The bad news is it’s a very complicated decision, but the good news is the reason it’s complicated is because we have a lot of good options. So, as I said, there are some people for whom chemotherapy would still be an option. One of the benefits of that is that it’s intravenous, i.e. there’s no copays for the patient. It’s administered over a finite period of time. Generally, six months.

And then, most patients will get several years of remission after that where they don’t have to be on any treatment. However, we now have what we call the small molecules or the targeted therapies and those come in two major categories. One is called BTK inhibitors. And there we have two drugs available in the same family, if you will. One is ibrutinib. One is acalabrutinib.

And then we have a different category of oral treatment where we only have one drug, which is a BCL-2 Inhibitor, which is Venetoclax. So, what these drugs do, they’re not chemotherapy, but they interfere with certain proteins in the CLL cell. And by doing that, cause the cell to die off.

Katherine:

Okay. What do you feel is the patient’s role in this decision?

Dr.Susan O’Brien:

Well, I think the patient plays a key role, which they usually do when there’s options because then you have – you with your doctor have to make a choice. So, for example, we talked about chemotherapy is time limited and you generally will be done after six months in contrast, with the BTK inhibitors, those are given indefinitely. They’re pills but given indefinitely for several years.

With Venetoclax it’s given with an antibody, which is given intravenously but the Venetoclax can be stopped after 12 months. So, the side effect profiles are different also. So, we have to take into consideration the duration of the therapy as well as the side effect profiles in determining what might be best for that patient.

How Do You Know If Your CLL Treatment Is Working?

How Do You Know If Your CLL Treatment is Working? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

How do you know if a chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treatment approach is effective? Dr. Susan O’Brien, a Hematology-Oncology specialist, explains how CLL treatment response is monitored.

Dr. Susan O’Brien is the Associate Director for Clinical Science, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

What Are Common CLL Treatment Side Effects? What Are Common CLL Treatment Side Effects? |

How to Be A Partner in Your CLL Care How to Be A Partner in Your CLL Care |

Transcript:

Katherine:

But how is that treatment monitored to evaluate its effectiveness?

Dr. Susan O’Brien:

Well, generally the things we’re – the same things we’re look – the same things we’re looking at when we treat. Right? So, we’re looking at abnormal blood counts. We’re looking at enlarged lymph nodes or spleen. We have symptoms. So, those three things are looked at when the patient is on the therapy. Are the lymph nodes shrinking? Are the blood counts improving? Are their symptoms getting better?

So, the same way pretty much that we would follow a patient who’s not on a clinical trial is the way we follow them on a clinical trial. Now, if it’s a very new drug which has never been given to humans before, let’s say, those trials probably have more frequent surveillance than we might do with a drug that we are familiar with and know what to expect with it. So, sometimes the trials might have more surveillance, more visits, more tests.

But generally, if those tests or visits are required – are not considered standard of care, the companies pay for them. So, usually what’s billed to the insurance is only what we would do treating any CLL patient with an already available drug.

So, it doesn’t wind up costing the insurance or the patient any more to be on a clinical trial. And they might get actually – there is some data the patients on clinical trials get better care because they’re being monitored very carefully as part of the trial.

Should You Discuss a CLL Clinical Trial with Your Doctor?

Should You Discuss a CLL Clinical Trial with Your Doctor? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

Dr. Susan O’Brien, a Hematology-Oncology specialist, explains why patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) should consider a clinical trial and the role trials play in treatment and care.

Dr. Susan O’Brien is the Associate Director for Clinical Science, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

What Are Common CLL Treatment Side Effects? What Are Common CLL Treatment Side Effects? |

How Do You Know If Your CLL Treatment is Working? How Do You Know If Your CLL Treatment is Working? |

Transcript:

Katherine:

Dr. O’Brien, where do clinical trials fit in in all of this? Should patients discuss clinical trials with their physicians?

Dr. Susan O’Brien:

Absolutely. If we think of these great drugs that we have now, and I’ve mentioned ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, Venetoclax. Before those drugs were available, the only options were chemo. So, that means that people that went on the clinical trial, so let’s say with ibrutinib, have access to a really treatment changing revolutionary drug in CLL years before it was commercially available.

So, clinical trials can be a great way to have access to drugs or combinations. So, for example, right now there are some clinical trials looking at combinations of a BTK inhibitor and a BCL-2 inhibitor. So, the patient might say, “Well, why can’t you give me that combination, doctor?” “Well, technically I could.” If the drug is approved by the FDA, a physician can prescribe it really pretty much anywhere they see fit.

However, does insurance pay for it? That’s the trick. And these are very, very expensive drugs. And so, outside of an FDA approved combination, it probably wouldn’t – I wouldn’t be able to prescribe that combination because it wouldn’t get paid for and it would cost thousands and thousands of dollars. But on a clinical trial in general, the drugs are paid for.

Katherine:

Mm-hmm.

Dr. Susan O’Brien:

And so, clinical trials are testing, for example, combinations now, which are not standard and there are some preliminary data from some of these trials that look really promising, i.e. two drugs may be better than one. There are also patients who, perhaps we’re talking about younger patients now, who have kind of worked their way through the available therapies. And so, they might not have a standard therapy that’s really gonna work for them. And for whatever reason they might not be a good candidate for stem cell transplant.

And so, innovative or totally novel drugs that we don’t have that class of drugs available at all are also being tested in clinical trials and allow people access to them. So, sometimes it’s – I think some people think of it as, well, a last resort if the drugs that are out there don’t work. But don’t think of it that way, because as I mentioned, these combination trials are for people who’ve never had prior therapy, but their disease has progressed enough to need treatment and could potentially offer, at least at a preliminary level, looks like a dynamite combination of drugs.

So, it’s not just for people who failed other drugs or whose disease has failed other drugs. That could be one group that is particularly important for, but even patients who’ve never had treatment, there may be clinical trials that they would be highly interested in participating. And again, it generally has a big financial benefit too, because remember oral drugs have copays for cancer patients.

Is It Time to Treat Your CLL? What You Need to Know

Is It Time to Treat Your CLL? What You Need to Know from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

When it’s time to move forward with a chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treatment plan, what determines the best therapy for YOU? In this webinar, Dr. Susan O’Brien, reviews key decision-making factors, current CLL treatments and emerging research.

Dr. Susan O’Brien is the Associate Director for Clinical Science, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

Advocate for These CLL Genetic Tests |

|

|

Transcript:

Katherine:

Hello and welcome to the webinar. I’m Katherine Banwell, your host for today’s program. Today we’ll discuss how you could work with your physician to find the best CLL treatment path for you. Joining me is Dr. Susan O’Brien. Welcome Dr. O’Brien. Would you please introduce yourself?

Dr. O’Brien:

Sure. I’m Susan O’Brien. I’m the Associate Director for Clinical Sciences at the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center in Orange, California.

Katherine:

Excellent. Thank you. And a note before we begin. This program is not a substitute for medical advice. Please refer to your healthcare team. Many CLL patients start in a period called watch and wait. Would you give us a brief overview of this approach?

Dr. O’Brien:

Sure. The reason that we do watch and wait, or as some patients like to call it, watch and worry, is because many people present asymptomatically. So, for example, it’s very common that a patient might be found to have CLL because they go in for a routine physical and they have a slightly elevated lymphocyte count. So, many people have no symptoms at all. The average age of the disease is about 71.

So, people at the age of 71 often have what we call comorbidities. So, what does that mean? High blood pressure, high lipids, coronary artery disease. So, they also have a lot of comorbidities and even though right now we have great treatments for CLL that are generally well tolerated, all drugs do have side effects. So, if a person feels fine and the disease is not causing any problem in their life, why give them a treatment for it?

Particularly if we think that we don’t have a curative strategy. There may be a cure fraction for a small subset of patients with CLL who are young and have what we call a mutated immunoglobulin gene. But they’re a minority of most patients with CLL. So, what we want to do is keep people alive as long as we can with CLL until they likely die of other causes that people die of as they age. Heart disease, et cetera.

So, if they don’t need any treatment, we don’t want to expose them to the side effects. And some people, if you take all comers, everybody diagnosed with CLL, about a third of people will actually never need treatment for their disease. And so, that’s the idea behind it. That we’re sparing people side effects from treatments when they feel fine and their quality of life is perfectly good.

Katherine:

How do you decide when it’s time to treat?

Dr. O’Brien:

So, it’s very variable because there are different indications from treatment in CLL. When I’m teaching my fellows, what I say to them is you basically treat the disease when it’s causing a problem. There are published guidelines, but they’re guidelines. They’re suggestions about when you might need to treat. But we take into account a number of different things. And in two different people the indications for treatment could be completely different. So, let me give you two examples.

We could have a patient where they have big lymph nodes maybe in their neck, under their arms, in the groin, in the abdomen. And those nodes are getting bigger and bulkier to the point where they’re really problematic. That could be an indication for treatment. Other people might have very small lymph nodes but have very abnormal blood counts. So, their lymphocyte count could be really high. They could be starting to get anemic where their hemoglobin is dropping.

If you get too anemic, what’s going to happen? You’re gonna be symptomatic with fatigue and shortness of breath. So, we want to intervene not at a time when the disease is not causing any problems, but we also have to kind of find a happy medium. We don’t want to intervene – and wait until the patient is sort of bedridden and then start to do anything about the disease.

So, it’s a little bit of a judgement call. We also take into account the symptoms that the patient might be having. Like, are they having really terrible night sweats and fatigue that’s impacting their daily activities? So, we look at symptoms, we look at blood counts, and we look at lymph nodes or bulk of disease.

Katherine:

Where does genetic testing fit into the plan to treat?

Dr. O’Brien:

There are certain tests that we definitely want to do before treatment. And some people have these tests done at diagnosis. So, the two main tests I would say are FISH, which just stands for fluorescence in situ hybridization, which is a fancy word for looking at chromosome abnormalities inside the CLL cell. The other thing we look at is the immunoglobulin mutation status. So, a patient’s immunoglobulin can be mutated or unmutated.

The immunoglobulin mutation status never changes. So, if a patient has had that test done once, they don’t have to have it repeated. However, the FISH, or the chromosome test, can change. So, it’s very important even if it was done at diagnosis that we repeat it at a time when a patient needs therapy. And why that’s so important is there is a particular chromosome abnormality called a 17p deletion where we know that those patients respond very poorly to chemotherapy.

And so, really should never receive chemotherapy and should receive a targeted therapy if that’s the case. There are other people that still could benefit potentially from chemotherapy, but not if they’re in that 17p deletion group.

Katherine:

All right. Dr. O’Brien, once it’s determined that it’s time to move forward with treatment, what do you take into consideration to help guide the treatment choice?

Dr. O’Brien:

Well, the good news and the bad news are kind of the same. The bad news is it’s a very complicated decision, but the good news is the reason it’s complicated is because we have a lot of good options. So, as I said, there are some people for whom chemotherapy would still be an option. One of the benefits of that is that it’s intravenous, i.e. there’s no copays for the patient. It’s administered over a finite period of time. Generally, six months.

And then, most patients will get several years of remission after that where they don’t have to be on any treatment. However, we now have what we call the small molecules or the targeted therapies and those come in two major categories. One is called BTK inhibitors. And there we have two drugs available in the same family, if you will. One is ibrutinib. One is acalabrutinib

And then we have a different category of oral treatment where we only have one drug, which is a BCL-2 Inhibitor, which is Venetoclax. So, what these drugs do, they’re not chemotherapy, but they interfere with certain proteins in the CLL cell. And by doing that, cause the cell to die off.

Katherine:

Okay. What do you feel is the patient’s role in this decision?

Dr. O’Brien:

Well, I think the patient plays a key role, which they usually do when there’s options because then you have – you with your doctor have to make a choice. So, for example, we talked about chemotherapy is time limited and you generally will be done after six months in contrast, with the BTK inhibitors, those are given indefinitely. They’re pills but given indefinitely for several years.

With Venetoclax it’s given with an antibody, which is given intravenously but the Venetoclax can be stopped after 12 months. So, the side effect profiles are different also. So, we have to take into consideration the duration of the therapy as well as the side effect profiles in determining what might be best for that patient.

Katherine:

Well, you talked about chemo and targeted therapies, but where – where’s stem cell treatment fit? Where does – where does stem cell treatment fit in and when is it considered?

Dr. O’Brien:

So, stem cell treatment – if we’re talking about stem cell transplant, allergenic stem cell transplant is a transplant where you need a donor and you receive stem cells from the donor. And that can be a curative therapy, but it can also be associated with significant risks including risk of dying from the transplant. Because we have so many effective therapies nowadays, we’re generally not needing to use allogenic transplant.

And what I mean by that is if these targeted therapies don’t cure people, and the jury is still out on that I would say, if we can sequence them such that we get five years from one, six years from another, et cetera, we’re going to be able to keep the patient alive long enough until they die of something else. So, where the stem cell transplant comes in is generally much younger patients with CLL.

I mentioned the average age is 71, but we have – all of us int eh field have seen patients, for example, in their 30’s. Well, yes, a sequence of therapies might not get that patient to a normal lifespan, because they’re so young to start. So, really the consideration is pretty much reserved for younger patients where we might need a curative strategy that we might not have otherwise.

But for older patients, we probably have enough active drugs now. We have other categories of drugs that we can use if the disease reoccurs. So, we have enough categories of drugs that I think we can keep most people who are the average at CLL alive for quite a long time.

Katherine:

What about CAR-T therapy? Where do we stand on that with that research?

Dr. O’Brien:

So, my answer is a little bit like allogenic stem cell transplant. CAR-T therapy is also associated with significant risks, but also significant benefit. Up until now, it’s pretty much been reserved because of the risks for patients who, to be frank, their disease has now kind of escaped everything. We don’t feel like we have great options that are similar and easier to use.

So, it can be effective, but it’s not something we do very early on because of the associated risks. If you take patients who go for CAR-T therapy, about 25 to 40% of them will wind up with some stay in the ICU. So, I’m really talking about some serious complications from these therapies.

It’s possible that as we learn how to minimize the toxicities of CAR-Ts, that they might become a more attractive strategy. And so, that could change with time. But the counterpoint to that is we’re having new drugs approved all the time for CLL. So, that gives us also more options before we would need to move to a CAR-T.

Katherine:

Dr. O’Brien, where do clinical trials fit in in all of this? Should patients discuss clinical trials with their physicians?

Dr. O’Brien:

Absolutely. If we think of these great drugs that we have now, and I’ve mentioned ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, Venetoclax. Before those drugs were available, the only options were chemo. So, that means that people that went on the clinical trial, so let’s say with ibrutinib, have access to a really treatment changing revolutionary drug in CLL years before it was commercially available.

So, clinical trials can be a great way to have access to drugs or combinations. So, for example, right now there are some clinical trials looking at combinations of a BTK inhibitor and a BCL-2 inhibitor. So, the patient might say, “Well, why can’t you give me that combination, doctor?” “Well, technically I could.” If the drug is approved by the FDA, a physician can prescribe it really pretty much anywhere they see fit.

However, does insurance pay for it? That’s the trick. And these are very, very expensive drugs. And so, outside of an FDA approved combination, it probably wouldn’t – I wouldn’t be able to prescribe that combination because it wouldn’t get paid for and it would cost thousands and thousands of dollars. But on a clinical trial in general, the drugs are paid for.

Katherine:

Mm-hmm.

Dr. O’Brien:

And so, clinical trials are testing, for example, combinations now, which are not standard and there are some preliminary data from some of these trials that look really promising, i.e. two drugs may be better than one. There are also patients who, perhaps we’re talking about younger patients now, who have kind of worked their way through the available therapies. And so, they might not have a standard therapy that’s really gonna work for them. And for whatever reason they might not be a good candidate for stem cell transplant.

And so, innovative or totally novel drugs that we don’t have that class of drugs available at all are also being tested in clinical trials and allow people access to them. So, sometimes it’s – I think some people think of it as, well, a last resort if the drugs that are out there don’t work. But don’t think of it that way, because as I mentioned, these combination trials are for people who’ve never had prior therapy, but their disease has progressed enough to need treatment and could potentially offer, at least at a preliminary level, looks like a dynamite combination of drugs.

So, it’s not just for people who failed other drugs or whose disease has failed other drugs. That could be one group that is particularly important for, but even patients who’ve never had treatment, there may be clinical trials that they would be highly interested in participating. And again, it generally has a big financial benefit too, because remember oral drugs have copays for cancer patients.

Katherine:

Right. But how is that treatment monitored to evaluate its effectiveness?

Dr. O’Brien:

Well, generally the things we’re – the same things we’re look – the same things we’re looking at when we treat. Right? So, we’re looking at abnormal blood counts. We’re looking at enlarged lymph nodes or spleen. We have symptoms. So, those three things are looked at when the patient is on the therapy. Are the lymph nodes shrinking? Are the blood counts improving? Are their symptoms getting better?

So, the same way pretty much that we would follow a patient who’s not on a clinical trial is the way we follow them on a clinical trial. Now, if it’s a very new drug which has never been given to humans before, let’s say, those trials probably have more frequent surveillance than we might do with a drug that we are familiar with and know what to expect with it. So, sometimes the trials might have more surveillance, more visits, more tests.

But generally, if those tests or visits are required – are not considered standard of care, the companies pay for them. So, usually what’s billed to the insurance is only what we would do treating any CLL patient with an already available drug.

So, it doesn’t wind up costing the insurance or the patient any more to be on a clinical trial. And they might get actually – there is some data the patients on clinical trials get better care because they’re being monitored very carefully as part of the trial.

Katherine:

Let’s turn to patient self-advocacy. How can patients feel confident in speaking up and becoming a partner in their own care?

Dr. O’Brien:

Yes, obviously for some people that’s going to be a lot harder than others. What I generally advice people is if you’re going in for your physician and you’re diagnosed with CLL, I would say this for any cancer because cancer is obviously a potentially life changing diagnosis, is you probably want to get an opinion with an expert. I would talk to my doctor first, ask them what their plan is so I know, and then see an expert in the field.

Then if the expert in the field says, “I think your doctor’s plan is great.” 1.) you’re now comfortable because you’ve got a second opinion, and 2.) that’s also a way, in my experience, to know if your doctor’s really gonna allow you to have an easy time participating. What I mean by that is that if your doctor is upset or finds it offensive, quite frankly you probably need a new doctor. That’s my take on that. Because that means they’re not going to be too open to your comments or you’re saying, “Well, I would prefer to do this.”

That’s just my quick take on how you can tell if it’s going to be easy or hard. But I think the relationship between the doctor and the patient is very important and you have to establish that relationship early on. If you go to a doctor who – where you start to ask questions and they’re in a hurry or they’re looking at their watch, you know that’s probably not the doctor that you want. I think most doctors realize that if they’re diagnosing a patient with a cancer, that’s going to be a pretty long clinic visit, because any patient is going to have a lot of questions to ask.

I also tell patients when you go to see a specialist or get a second opinion, bring somebody with you. It’s very well known that when patients have just been diagnosed with a cancer, they’re overwhelmed. Their emotional system is overwhelmed. Even if it’s “not a bad cancer”. Maybe early stage CLL. And that makes it very hard to process what a doctor is saying.

Particularly if they’re trying to give you quite a bit of information, which you need because you’ve just been diagnosed, and you need to know what to expect from the disease. So, having a friend or a spouse or a significant other there is really, really helpful.

Katherine:

Yeah. Yeah. That’s really good advice. Are there resources to help patients stay informed and educated?

Dr. O’Brien:

Oh, yes. Our Leukemia and Lymphoma Society is great at that. Lymphoma Research Foundation were two of the big ones. And then there’s patient spots. CLL Society is a very well-known one run by a physician who’s also a CLL patient. I know him very well. And they have online support meetings now.

They used to have them in person, but now they have them online. And those can be really helpful because that allows a patient to talk to another patient who has their same disease. So, there are quite a lot of resources for patients nowadays. Especially in our technology enabled world.

Katherine:

That’s great. We have a couple of questions from patients. Patrick asks, “I’ve discussed a treatment plan with my doctor, but I’d like to get a second opinion. What are your thoughts on that?”

Dr. O’Brien:

I think it’s a great idea. That’s exactly what I would do if I had a cancer. And again, I think Patrick made an important point that I’d like to emphasize. See what your doctor’s plan is first. Because then when you go to see the specialist or the second opinion, you can say, “This is what my doctor’s suggesting.”

And then if the specialist says, “Exactly what I would do.” But if you don’t know what your doctor is going to do – was suggesting to do when you go in to see the second opinion, it’s going to be really hard to make sure –put together that feeling of confidence that you’re on the right track.

Katherine:

Right. Right. To judge. A question from Julie. “How do you approach treating a relapse?”

Dr. O’Brien:

So, treating relapse we do the same thing that we do upfront. Namely “watch and wait”. So, for example, if a patient had a treatment on – let’s say they had some chemotherapy. And three or four years alter the lymphocyte count starts to go up, well, that technically would be indicating relapse.

But let’s say for the sake of discussion the person is asymptomatic, they feel fine, and their lymphocyte count is 20,000. Well, why do we need to do anything? So, in most cases we take the same approach of watch and wait when the disease comes back. And the first point at which it comes back is not always the time at which we need to initiate therapy.

Katherine:

Right. Right. Another question. Will is wondering, “If inhibitor treatments have to be taken forever?”

Dr. O’Brien:

Well, it depend on the group – the class. So, for the BTK inhibitors, all the trials so far have given those drugs indefinitely. For the BCL-2 inhibitor, Venetoclax, there are time limited regimens both in the frontline setting and in relapse. But realistically, I have talked to my patients who are going on a BTK inhibitor who say to me, “Do I really have to be on this forever?”

And so, my answer is, “I don’t know what life is forever, so I would never use that word. We generally use the word indefinite.” But what I’ve said to those patients is, “If you’re on the drug for a while – and I’m not talking months. I’m talking say two, three years. And you’re in a really good remission and you think you want to stop treatment. I’m not necessarily opposed to that.”

Because if you’re in a very good remission, even if it’s not complete, but most people who are not in complete remission, meaning they still have a bit of disease left, have very little disease if they’ve been on the BTK inhibitors for a while. So, maybe only some enlarged lymph node on a CAT scan or a little bit of disease in the bone marrow.

But basically, most people after a couple years, they’re blood counts are normal, they feel fine, unless they’re having side effects from the drug and their physical exam is normal. So, I’ve told my patients if you want to go off, I expect you’d probably be off for even a couple years. And then we could always restart therapy potentially with that drug again or with one of the other drugs.

So, I think it’s important to let people know that they have options. But I will say that all of the clinical trials with the BTK inhibitors have given those drugs basically until the patient loses their response or there’s a toxicity where they just don’t want to take the drug anymore.

Katherine:

Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. One last question from Jen. “What should be considered related to side effects when choosing a treatment plan?”

Dr. O’Brien:

Well, the BTK inhibitors have some side effects. They can cause diarrhea, but that’s usually mild and self-limited. They can sometimes cause joint aches or arthrology. They – the two probably most serious side effects are atrial fibrillations, which is an irregular heart rate. But that generally is not frequent and tends to occur mainly in older men with heart disease.

Katherine:

Hmm.

Dr. O’Brien:

They also are more likely – they impact the platelet function. So, they can more likely cause bleeding, but it’s typically minor bleeding like a bruise. Major bleeding is quite rare. In general, I’m outlining a lot of side effects, but remember not all side effects occur in everybody and there’s some people who don’t have any.

For the BCL-2 inhibitor, Venetoclax, one of the things we have to be very careful of when a person first goes on that and this would be particularly true if they have a very high lymphocyte count or a bulky lymph nodes, it that drug can cause something called tumor lysis. Tumor lysis, lysis is just a fancy word for breakdown, is where the disease responds so rapidly that their lymph nodes shrink very quickly. Lymphocyte comes down, which sound really good.

But what can happen is that breakdown of the cells can release potassium which can cause heart arrythmias. The cells can clog the kidneys and cause kidney failure. So, we have to be very careful about that when we start. And the way that drug is started is it comes with a starter pack actually to help make it easy where you go up, you start at a low dose, and go up weekly until we get to the target dose.

But we have to monitor very carefully during that escalation phase. The other thing that the Venetoclax can cause is neutropenia, meaning low neutrophil counts. What – that’s important because neutrophils are what we use to fight infection. So, if we get low neutrophil counts, the options are either to add a growth factor transiently, in other words a shot to – the subcutaneous injection that stimulates the bone marrow to release neutrophils. Or if it’s really a persistent problem, then we can go down on the dose of Venetoclax.

Katherine:

All right. How do you feel – how do you feel about the future of CLL treatment? Are you hopeful?

Dr. O’Brien:

Absolutely. I think we’ve had something like six drugs approved in the last seven years, which is mindboggling. I think in the 30 years before that, we didn’t even have six drugs approved. That’s how rapidly – it’s mindboggling, really. That’s how rapidly the field is moving forward. And not just CLL, but other cancer fields also are moving at a very dizzying pace.

Which is great because that – anything that gives us more options is wonderful. So, I am very, very optimistic about CLL going forward. And I’m also very hopeful that some of these combination regimens might actually be – small molecules might actually be curative in the long run. But I will say it’s way too early to know that.

Katherine:

Are there emerging treatments that patients should know about?

Dr. O’Brien:

So, one of the categories we haven’t talked about, where there actually are two FDA approved drugs, are PI3K inhibitors – that’s another oral small molecule. They’re not approved for frontline therapy. So, that’s kind of why we weren’t talking about them so much today where we’re talking about making a choice for the first therapy. But they are approved for patients where the disease reoccurs.

And there’s two of those as we mentioned. We have antibodies, which we really haven’t talked about very much, and then there’s new classes of drugs that are being explored in clinical trials. So, for example, there are interesting drugs which are antibodies that bind to the patient’s own T-cells and they also mind the CLL cells and they redirect the T-cells towards the CLL cells.

Kind of like CAR-T but inside the body without having to take out the T-cells. So, those are really interesting class of drugs. None have been yet approved in CLL or lymphoma, but I think those are on the horizon and looking very promising.

Katherine:

Hmm. One last question, Dr. O’Brien. In this uncertain time, do you have any advice related to COVID-19 for CLL patients?

Dr. O’Brien:

It’s a hard time for everybody and particularly CLL patients because we know that they’re immunocompromised by – and even if you’ve never been treated and you probably never get any infections, which is quite a number of people with CLL, unfortunately you do have to think about yourself as being a high-risk patient.

So, masks are very important. Washing hands. Avoid – social distancing. Avoiding crows. It’s really important for patients with CLL to follow those same guidelines that we’re giving to everybody. But very important for them because they are in a higher risk group.

Katherine:

How do you feel telemedicine is working for CLL patients?

Dr. O’Brien:

Telemedicine works I’d say better for CLL patients than some other patients, particularly watch and wait patients. Obviously the one thing that we can’t do in telemedicine is a physical exam. But in patient we can get – have patients get their blood counts done and then talk to them and see how symptomatic they are and know what their blood counts indicate anything is changing.

And then what I’ve been doing is, say I have a watch and wait patient – or it also applies let’s say to a patient who’s been on ibrutinib for years now and they’re in remission. There’s probably nothing to exam anyway. Right? So, those patients are good. I think it’s not going to work very well if you’re starting a new treatment. But for people who are watch and wait or have been on established treatments that are doing well, it works really well.

And then you can use the video visit if the patient says, “This is going on.” Whatever it is. “And I think I’m worried about this or I have this pain here.” Or whatever. If that’s an issue, you can always then schedule a regular visit. Right?

But I think that it – because it’s a chronic disease as opposed to acute leukemia where you really can’t do video visits, I think it lends itself to it very well. And my expectation is that moving forward, even after hopefully COVID has died down or we have a vaccine, that video visits are definitely here to stay.

Katherine:

Yeah. Yeah. I agree with you. What about patients who are fearful going into a medical center? Do you have any advice for them?

Dr. O’Brien:

Usually – and it does vary. I also would be nervous if it was a hospital-based place where I had to go for my visit. But for example, where we are in the cancer center, it’s a completely separate building. Everybody is temperature checked before they get in. Everybody has to fill out a questionnaire about their symptoms. If they do have a low-grade temperature, we immediately triage them to another area.

So, actually I think the cancer center is probably a pretty safe place to be. Probably safer than the grocery store in that sense, because of the screening and the testing of the temperature of everybody who comes in there. And, of course, everybody has a mask on.

So, I would be probably a little bit weary in a hospital setting where they may be many sick patients hospitalized with COVID. But I think in a lot of clinic buildings or freestanding buildings, I probably would not be that worried.

Katherine:

Well, Dr. Susan O’Brien, thank you so much for joining us today. And thank you to all of our partners. To learn more about CLL and to access tools to help you become a proactive patient, visit powerfulpatients.org. I’m Katherine Banwell. Thank you so much for joining us.

How Does COVID Impact CLL Patients?

How Does COVID Impact CLL Patients? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

|

|

Transcript:

Dr. Philip Thompson:

There was a large ISH study published, I think, in Lancet Oncology, recently, from the UK, where they looked at outcomes for patients with cancer. And of course, it was all patients with cancer, not specifically CLL, specifically blood cancers. But I think there were roughly 200 patients with hematologic malignancies.

And the interesting thing that I noticed, there were that patients who had recent chemotherapy, which I might have expected to be a really high-risk feature for a poor outcome, actually didn’t do any worse than patients who hadn’t recently been treated.

By far, the most important predictors of outcome for patients were whether their cancer was controlled or not, number one. And then other co-morbidities that patients had, like lung disease, advanced age, that sort of thing. So, actually, we need to see more data from more – from datasets that have more patients with CLL. But it seemed like the type of treatment mattered less than whether the disease was controlled and what other problems the patient had in terms of predicting their outcome from COVID.

So, I am taking that information with a – we have to, as I said, see more data. But I’m not going to use COVID as a reason not to patients who need treatment.

We may stretch things out somewhat in people where the decision is really well, and maybe you don’t definitely need to treat. But I don’t want to see people get into really severe trouble from their CLL because we’re trying to delay treatment because of COVID. Because that might actually be counterproductive. Because people with very uncontrolled CLL, if they were to get the infection, may actually have inferior outcomes to people whose disease is controlled.

Partnering With Your Doctor on CLL Treatment Decisions

Partnering With Your Doctor on CLL Treatment Decisions from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

Which CLL treatment could be right for you? Dr. Steven Coutre, a CLL specialist, reviews current approaches and explains why patients should stay informed about emerging options.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

|

|

Transcript:

Dr. Steven Coutre:

Well, any decision about treatment is, of course, a joint decision between the physician and the patient. It’s our job to really educate each individual patient about their options and also, I think, very importantly, determine what their goals are. You don’t really follow a strict algorithm. It’s really making a decision for each individual patient.

So, of course that takes into account other medical conditions they may have, the nature of their disease, why it is that we’re treating that individual, what we’re trying to accomplish, and very importantly, what the goals of therapy are for that individual. That may be very different, for example, for somebody who’s quite young versus somebody who’s older or who might have significant medical comorbidities.

I think patients are always well served by asking questions about the treatment, side effects of treatment, of course, these days, cost comes into play, so I think we have an obligation to let patients know the differences between the therapies because often we have choices about a therapy. There isn’t any one best therapy, for example. It’s often a number of choices, and sometimes that can be very, in some ways, confusing for patients, because they wanna know, “Well, what’s the best therapy?” and as I mentioned, it’s not so much what’s the best. It’s what’s the best for that patient, and many times that’s choices of treatment.

Some are time limited, for example. Some are continuous therapies. So, there’s plusses and minuses, and again, it all goes back to what’s your goal for that individual patient, what are their preferences in terms of the treatment that they want to receive.

The drugs that I mentioned earlier are Bruton Acalabrutinib, Venetoclax, for example. These are really the first of our new really transformative drugs for CLL. Drugs, along sometimes, with our antibodies, Rituximab and Obinutuzumab, which are really replacing the use of chemotherapy in treating the disease. So, moving forward, we’re looking at combinations of these drugs. Can we drive responses deeper? That would lend itself to stopping therapy, in some case, instead of using continuous daily therapy as we currently do with drugs like Ibrutinib or Acalabrutinib.

So, that’s the major focus right now. There, of course, will be other new drugs. There’s a third drug, Zanubrutinib, which is another BTK inhibitor, so that’ll probably play a role in treating CLL. There may be differences in side effect profiles between these drugs. There isn’t any new drug that we’re looking at currently that’s far enough along to say that it’s gonna be yet another fundamentally different, revolutionary therapy for CLL. But those, of course, can come along as we learn more about the biology of the disease.

You may have heard about CAR T-Cell Therapy, where you’re using your body’s own immune system to try to target the cancer. This has been very successful and is actually approved for use in other diseases, like large cell lymphoma, for example, but it remains very much investigational in CLL. There are also other clever ways of trying to achieve the same, endpoint, that is, using your own immune system to target the cells, that are simpler than CAR T-Cell Therapy and those kinds of approaches are also in clinical trials.

So, when you’re having the discussion about treatment, it’s always good to learn about what the latest therapies may be, even if they are investigational. I think that’s how we move the field forward and, of course, the newer drugs that we have brought forward came from clinical trials that patients greatly benefitted from. So, always ask your physician about clinical trials. Another great source for that, I think, is the Leukemia Lymphoma Society. They’re very patient-focused, they’re very up to date on the latest therapies and the latest trial results. They have a very robust presence, both online, and also, generally locally. There’s local chapters. So, I would encourage you to reach out to them for information.

CLL & COVID 19: What Do Patients Need to Know?

CLL & COVID 19: What Do Patients Need to Know? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

PEN-Powered Activity Guide: Utilizing Telemedicine Tools & Staying Connected |

|

Transcript:

Dr. Steven Coutre:

Well, of course, we are in the COVID era. We don’t know how long this is going to last. And so, a very common questions that comes up from our patients with CLL is what impact does this have on them and are they more susceptible, you know, the natural things that people wanna know. With CLL in general, there probably is some compromise to the immune system, but it’s really hard to measure or quantify. Certainly, individuals who’ve had a lot of chemotherapy in the past, who have advanced disease are more susceptible to infections. In contrast, someone who’s without symptoms, has a low burden of disease probably is close to being like somebody who doesn’t have CLL. So, there’s certainly a spectrum.

Really, we just try to advise following the guidelines that we are all following in terms of social distancing at present, at being aware of being around others too closely, or those who may have symptoms. So, I think, in a way, what everyone is doing now is something that is beneficial to patients with CLL, and certainly other cancers, with respect to infection risk.

Now, what about do we have any information? Is somebody with CLL more susceptible to getting COVID? What if you do get the infection? Is it going to be more severe because you have underlying CLL? And, at least in general terms, the answer seems to be no. That’s really just based on experience, anecdotal experience, certainly in areas like New York City or Italy, for example, where infectious rates have been quite high. Colleagues have commented that their patients don’t seem to be more ill simply because they have the underlying disease or because they’re on a certain treatment, for example.

There’s actually some very interesting data suggesting that perhaps the BTK inhibitors, Ibrutinib, Acalabrutinib, et cetera, might actually confer benefit, might lessen some of the consequences of the infection, and as a result, large clinical trials have started for patients without CLL. Just anyone who has a significant COVID infection who’s hospitalized, they’re testing that hypothesis. So, it’ll be very interesting to see what we learn from this. Perhaps what we’ll learn is that being on a drug like that might actually be beneficial.

It’s certainly natural to be hesitant to come into a healthcare facility because of the risk of infection, and certainly that’s gonna vary quite a bit depending on where you are. At the height of the pandemic in New York City, of course, a lot of concern on the part of patients going into a hospital clinic, for example. Whereas, at our institution, the impact has been quite low. All institutions, of course, have taken any precautions they can to limit exposure, so, I’ve often told my patients that it’s probably safer to come into our clinic and get your blood drawn or see someone if you need to than going to the grocery store, for example, in terms of exposure.

But that’s very different than saying the same thing in the middle of New York City. So, I think you have to deal with each situation as it arises, and one would hope that your physician can give you guidance. And I think, in particular, what we can do is really decide how important it is to see somebody in person or have them come in and get a lab test there. I think in many, many, many cases, that can be avoided for the time being.

And that also is an important point, that we can provide reassurance that you know, you’re used to coming in every four months or every six months and having things checked, and in many cases we can reassure that individual that it’s okay to wait. It’s not critical to get that information right now.

So, remember that what we often emphasize in evaluating someone and making decisions when to treat is three things. It’s how you feel, what your exam is like, and what your blood counts look like. So, of course, you know how you feel. If something changed, you’re having night sweats, or a lot more fatigue, is it significantly different? Of course, you typically know if anything’s changing with your exam. Are your lymph nodes getting enlarged?

Do you notice discomfort in your abdomen because of an enlarging spleen?

And so, two of the three things you can sort of self-assess, in a way, and then based on what your blood counts have been showing over time, your physician can factor that in and decide how important it is to get that test now. And as I mentioned, in many, many cases, it’s perfectly fine to delay that. So, it’s not as difficult as it might seem to you to be able to come up with a reasonable assessment about how somebody might be doing, even in the absence of seeing them and doing an exam in person.

How Can CLL Patients Take Advantage of Telemedicine?

How Can CLL Patients Take Advantage of Telemedicine? from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

In light of the global pandemic, many providers expanded their telemedicine options so that patients can connect with their physicians virtually and avoid in-person visits. Expert Dr. Steven Coutre explains how this approach could benefit people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Dr. Steven Coutre is a Professor of Medicine in the Hematology Department at Stanford University Medical Center. Learn more about this expert.

See More From The Pro-Active CLL Patient Toolkit

Related Resources

|

PEN-Powered Activity Guide: Utilizing Telemedicine Tools & Staying Connected |

|

Transcript:

Dr. Steven Coutre:

Well, we are in a new era, at least temporarily, and, for example, we’ve switched almost exclusively to video visits. This had largely been used for patients who lived in remote areas. They didn’t have good access or ready access to healthcare providers, and so, the government reimbursed for those kinds of visits, but not for somebody who lived close by, for example.

Well, that all changed dramatically with the COVID infections, even for our patients on clinical trials. And we’ve done the grand experiment that never would have been done otherwise, of just suddenly doing all video visits, and I must say, it’s worked out quite well so far. I think patients are quite satisfied with it, by and large. It allows them to have their questions answered and continue to have appropriate monitoring if they’re on therapy, or even if they aren’t. And so, I think, when things improve, this will continue, to some extent. So, right now, I would expect that any CLL patient would have ready access to their hematologist or oncologist via video visit.

And also, I think this whole situation has promoted a lot more video conferencing, educational video conferencing. Not having to physically attend a conference in order to get information. So, I think they’ll see a lot more educational resources out there online for them.

Well, of course, with CLL, we’re also very interested in blood counts, as are our patients, and if we’re doing remote visits, or even if they live fairly close but aren’t coming in, we do try to get the lab work done, but that’s worked out quite well. We’re used to dealing with patients coming from far distances, and so, in the past, if we wanted to get a lab result in between visits, we would simply make those arrangements with their local lab. Everybody tends to have an internist, a family doctor that they see, and so they’re familiar with getting lab tests done near where they live, and in all cases, we’ve been able to accommodate that.

And now with the increasing of electronic medical record usage and interlinking of medical record systems, we can, for example, get lab tests done at a local lab and have those. Actually, those results are directly imported into the medical record. So, they’re easily accessible to us. So, I must say, it’s been a pleasant surprise to see how well this has worked.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

What is Leukemia?

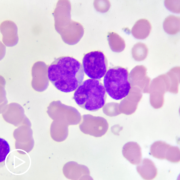

Leukemias are cancers that start in cells that would normally develop into different types of blood cells. It is a cancer of the body’s blood-forming tissues, including the bone marrow and the lymphatic system. Most often, leukemia starts in early forms of white blood cells, but some leukemias start in other blood cell types.

There are several types of leukemia, which are divided based mainly on whether the leukemia is acute (fast growing) or chronic (slower growing), and whether it starts in myeloid cells or lymphoid cells. The main types of leukemia include:

- Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL)

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

- Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML)

- Other – Other, rarer types of leukemia exist, including hairy cell leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and myeloproliferative disorders

In this article we will be focusing on Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) since it is the most frequent acute leukemia in adulthood.

What is Acute Myeloid Leukemia?

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a cancer of the blood in which the bone marrow makes abnormal cells. The “acute” in Acute Myeloid Leukemia denotes the disease’s rapid progression In AML, myeloid stem cells usually mature into abnormal myeloblasts, or white blood cells. But, they sometimes become abnormal red blood cells or platelets. As they multiply, they overwhelm the normal cells in the bone marrow and blood. The cancer cells can also spread to other parts of the body.

This type of cancer usually gets worse quickly if it is not treated. It is the most common type of acute leukemia in adults. AML can also be referred to as:

- Acute myelogenous leukemia

- Acute myeloblastic leukemia

- Acute granulocytic leukemia

- Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia

Types of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Knowing the subtype of AML can be very important, as it sometimes affects both a patient’s outlook and the best treatment. Most types of AML are based on how mature (developed) the cancer cells are at the time of diagnosis and how different they are from normal cells. The different types of AML include:

The French-American-British (FAB) Classification

- M0 – Undifferentiated acute myeloblastic leukemia

- M1 – Acute myeloblastic leukemia with minimal maturation

- M2 – Acute myeloblastic leukemia with maturation

- M3 – Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)

- M4 – Acute myelomonocytic leukemia

- M4 eos – Acute myelomonocytic leukemia with eosinophilia

- M5 – Acute monocytic leukemia

- M6 – Acute erythroid leukemia

- M7 – Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia

World Health Organization (WHO) Classification

- AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities, meaning with specific chromosomal changes

- AML with multilineage dysplasia, or abnormalities in how the blood cells look

- AML, related to therapy that is damaging to cells, also called therapy-related myeloid neoplasm

- AML that is not otherwise categorized

- Myeloid sarcoma

- Myeloid proliferations related to Down Syndrome

- Undifferentiated or biphenotypic acute leukemias

Cytogenetics

AML can also be classified by the cytogenetic, or chromosome, changes found in the leukemia cells. Changes in certain chromosomes help diagnose cancer, plan treatment, or find out how well treatment is working. Chromosomal changes are commonly grouped according to the likelihood that treatment will work against the subtype of AML.

All chromosomes are numbered from 1 to 22. And, sex chromosomes are called “X” or “Y.” The letters “p” and “q” refer to the “arms” or specific areas of the chromosome. Some of the types of genetic changes found in AML include:

- A translocation, which means that a chromosome breaks off and reattaches to another chromosome

- Extra copies of a chromosome

- A deletion of a chromosome

Some of the most common chromosomal changes are grouped as follows:

- Favorable. Chromosomal changes associated with more successful treatment include abnormalities of chromosome 16 at bands p13 and q22 [t(16;16)(p13;q22), inv(16)(p13q22)] and a translocation between chromosomes 8 and 21 [t(8;21)].

- Intermediate. Changes associated with a less favorable prognosis include normal chromosomes, where no changes are found and a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 11 [t(9;11)]. Many other subtypes are considered part of this group, particularly those with 1 or more specific molecular changes. Sometimes, extra copies of chromosome 8 or trisomy 8 may be classified as intermediate risk over unfavorable (see below).

- Unfavorable. Examples of chromosomal changes that are associated with less successful treatment or with a low chance of curing the AML include extra copies of chromosomes 8 or 13 [for example, trisomy 8 (+8)], deletion of all or part of chromosomes 5 or 7, complex changes on many chromosomes, and changes to chromosome 3 at band q26.

Symptoms of AML

The signs and symptoms of AML vary based on the type of blood cell affected. They are generally nonspecific and warrant investigations for proper diagnosis. The signs and symptoms of AML are:

- Fever

- Pain in bones and joints

- Pale skin

- Easy bruising and contusions

- Recurrent infections

- Unusual bleeding, epistaxis, bleeding gums

Causes and Risk Factors for AML

Although the cause of AML is not known, several factors are associated with an increased risk of the disease. The following factors may raise a person’s risk of developing AML:

- Age – AML is becomes more common as people get older

- Being Male – AML is more common in males than in females

- Smoking – Cancer-causing substances in tobacco smoke are absorbed by the lungs and spread through the bloodstream to many parts of the body

- Genetics – Researchers are finding that leukemia may run in a family due to inherited gene mutation

- Chemicals – Long-term exposure to chemicals like benzene, found in petroleum, cigarette smoke, and industrial workplaces, raises the risk of AML

- Previous Cancer Treatment – People who have received chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy for other types of cancer, such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and lymphoma, have a higher risk of developing AML in the years following treatment.

- Other Bone Marrow Disorders – People who have other bone marrow diseases can develop AML over time

How is Acute Myeloid Leukemia Diagnosed?

No screening exams exist for leukemia.

Doctors often discover that a person has chronic leukemia through routine blood testing. They may also rely on their experience and current knowledge of the disease.

If your doctor suspects you may have leukemia, he or she will order specific diagnostic tests such as a:

- Blood test

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Spinal tap

- Genomic testing

Is Acute Myeloid Leukemia Hereditary?

Leukemia does not usually run in families, so in most cases, it is not hereditary. However, people can inherit genetic abnormalities that increase their risk of developing this form of cancer.

For example having a family history of other blood disorders increases your risk of getting AML. These disorders include:

- Polycythemia Vera

- Essential Thrombocythemia

- Idiopathic myelofibrosis.

Some syndromes that are caused by genetic mutations (abnormal changes) present at birth seem to raise the risk of AML. These include:

- Down syndrome

- Ataxia telangiectasia

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- Klinefelter syndrome

- Fanconi anemia

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- Bloom syndrome

- Familial Platelet Disorder syndrome

Newly Diagnosed AML Advice from an Expert

Dr. Elizabeth Bowhay-Carnes of UT Health San Antonio MD Anderson Cancer Center provides advice for patients facing an AML diagnosis, including:

- Understand who your care team is including the main attending physician and the main nursing contact/support person would be

- Designate a family member or friend to play the main supportive role

Preparing for Your AML Appointment

Your first appointment can be overwhelming and can be hard to grasp the realistic expectations of life during the AML treatment phase. Here are some tips and tricks to prepare you for your first appointment:

- Write down any and all questions you have before coming to the doctor’s office

- Bring a notepad to the appointment to jot down notes about what is said during the appointment or ask if you can record your visit

- Consider your values and expectations of your quality of life

- Keep copies of your medical records

- Bring a friend or a family member to your appointments to help you retain all the information discusses

- Consider all your treatment options, including any clinical trials available to you

Treating Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Treatment of AML depends on several factors, including the subtype of the disease, your age, your overall health and your preferences. The types of treatment include:

- Chemotherapy – the primary treatment options that uses chemicals to kill cancer cells

- Targeted therapy – medications that target cancer cells, but don’t affect healthy cells. This type of treatment usually has less side effects

- Other drug therapy

- Stem Cell transplant – also called a bone marrow transplant, helps re-establish health stem cells by replacing unhealthy bone marrow with leukemia-free stem cells that will regenerate health bone marrow

- Clinical trials – can involve therapy with new drugs and new drug combinations or new approaches to stem cell transplantation

it is often a good idea to seek a second opinion. A second opinion can give you more information and help you feel more confident about the treatment plan you choose.

What You Can Expect From AML Treatment

Based on your treatment options that you have discussed with your care team, it Is important you understand how treatment may affect you. Some things you should discuss with your care team and loved ones include:

- Your personal goals and values

- Results you can expect

- Potential side effects

- Palliative care

- How treatment may affect your life

- The financial costs of treatment

Recovery and Survival

Leukemia represents 3.5 percent of all new cancer cases in the United States, and it is the seventh leading cause of cancer death. The outlook for leukemia patients depends on which type of leukemia they have, their overall health, and their age.

In the case of AML, it makes up 32% of all adult leukemia cases and there will be about 19,940 new cases of AML in the United States this year. Remission in AML is usually defined when the bone marrow contains fewer than 5% blast cells. For most types of AML, about 2 out of 3 people with AML who get standard treatment go into remission. The 5-year survival rate for people 20 and older with AML is about 25%. For people younger than 20, the survival rate is 67%.

Sources:

“Treatment.” Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment | Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, 26 Feb. 2015, www.lls.org/leukemia/acute-myeloid-leukemia/treatment.

“Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version.” National Cancer Institute, www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/patient/adult-aml-treatment-pdq.

“Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Subtypes and Prognostic Factors.” American Cancer Society, www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-myeloid-leukemia/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-classified.html.

“Leukemia – Acute Myeloid – AML – Subtypes.” Cancer.Net, 18 Aug. 2017, www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-acute-myeloid-aml/subtypes.

“Leukemia Types, Symptoms, and Treatments.” UPMC HIllman Cancer Center, hillman.upmc.com/cancer-care/blood/types/leukemia.

“Treating Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).” American Cancer Society, www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-myeloid-leukemia/treating.html.

“Acute Myelogenous Leukemia.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 27 Dec. 2017, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/acute-myelogenous-leukemia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20369115.

“Treatment Response Rates for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).” American Cancer Society, www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-myeloid-leukemia/treating/response-rates.html.

“Leukemia – Acute Myeloid – AML – Statistics.” Cancer.Net, 19 Feb. 2020, www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-acute-myeloid-aml/statistics.

A Look at Leukemia

What is Leukemia?

As with many other cancers, leukemia is not a singular disease. There are many types of leukemia, and while it is a common childhood cancer, leukemia actually occurs more often in older adults. Leukemia is the most common cancer in people under the age of 15, but it is most likely to affect people who are 55 or older. There are more than 60,000 cases of adult leukemia diagnosed each year, and it is more common among men than women.

Leukemia is a broad term that describes cancer of the blood or bone marrow. It starts when the DNA of developing blood cells are damaged and the bone marrow makes abnormal cells. The abnormal blood cells are the leukemia cells which grow and divide uncontrollably. Unlike healthy cells that follow a life cycle, the leukemia cells don’t die when they are supposed to so they continue to build up, eventually overcrowding the blood. They crowd out normal white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets so those normal cells can’t grow and function. Eventually, there are more cancer cells than healthy cells in the blood. The type of leukemia is determined based on which blood cells are affected by the abnormal cells. Leukemia usually affects the white blood cells, called leukocytes, but can occur in other blood cells. There are four main types of leukemia: chronic, acute, lymphocytic, and myelogenous.

Leukemia that grows slowly is called chronic leukemia. The cancer cells form very slowly so the body can also continue to form healthy cells, but over time the cancer cells continue to grow and the leukemia worsens.

Acute leukemia grows very quickly and gets worse really fast. It has been identified as the most rapidly progressing cancer, and it can develop and grow in a matter of days or weeks.

Lymphocytic leukemia forms in the part of the bone marrow that makes lymphocytes, which are white blood cells that are also immune cells. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is most common in older adults and makes up about 25 percent of adult leukemia cases. It is more common in men than women and is very rare in children. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) also affects older adults, but children younger than five have the highest risk of developing it.

Myelogenous leukemia forms in the bone marrow cells that produce blood cells, rather than forming in the actual blood cells. Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) accounts for about 15 percent of all leukemia cases in the United States. CML develops mostly in adults and is very rare in children. Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is a rare cancer that develops quickly with symptoms of fever, difficulty breathing, and pain in the joints. It can be caused by environmental factors, and develops more often in adults than children, and more often in men than women.

There are also several less common types of leukemia. Most of these types are chronic, and each year in the United States, about 6,000 cases of these less common leukemias are diagnosed.

- Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) develops from myeloid cells.

- Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) is typically found in very young children and is another type of myeloid leukemia.

- Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a subtype of AML.

- Hairy cell leukemia is slow growing, chronic, and makes too many B cells that appear hairy wen viewed under a microscope.

Leukemia Possible Risk Factors

There are several risk factors linked to leukemia. There are environmental factors and genetic reasons why some people might develop leukemia. Some of the factors can be controlled while others can not. Age, smoking history, and exposure to hazardous chemicals are all possible risk factors. Other risk factors may include exposure to chemicals or medical treatments, personal health history, and family history. Some of the possible risk factors need more study to determine a definite link to leukemia, but being aware of your potential risk is important.

If you were exposed to chemotherapy or radiation therapy for another cancer you have a higher chance of getting leukemia later in life. Also, children who took medications to suppress their immune systems, such as after an organ transplant, may develop leukemia. Exposure to chemicals such as benzene and formaldehyde, often found in cleaning products, hair dyes, and embalming fluid, may also increase your risk of developing leukemia. Smoking and exposure to workplace chemicals like gasoline, diesel and pesticides could also be a risk factor.

There are several syndromes, conditions, and genetic disorders that can also increase leukemia risk. Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a hereditary disorder, is linked to leukemia, and children with Down syndrome have a two to three percent increased risk of developing acute myeloid or acute lymphocytic leukemia. Other genetic disorders that increase leukemia risk are Fanconi anemia, and dyskeratosis congenita (DKC). The inherited immune system conditions ataxia-telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome, Schwachmai-Diamond syndrome, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome also increase the risk of leukemia. Risk is also increased in patients with a history of blood disorders such as myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and aplastic anemia. There are also viruses, such as the human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1), linked to leukemia.

Family history can also play a role in the development of leukemia. Having a sibling with leukemia is a risk factor, and having an identical twin with leukemia gives you a one in five chance of developing it yourself.

Preventing Leukemia

There are no known ways to prevent leukemia; however, being aware of risk factors and attempting to reduce them could help. Studies have linked leukemia to smoking and obesity, so quitting smoking and having a healthy body weight could help prevent leukemia. In addition, avoiding heavy exposure to dangerous chemicals might decrease your risk.

Signs and Symptoms

There are no reliable early screening methods for leukemia and, especially in chronic leukemia, the symptoms may not be very noticeable early on. Symptoms such as fatigue and fever may not be alarming at first, and could be mistakenly attributed to other causes. Acute leukemia symptoms come on faster and are typically more noticeable. All types of leukemia can have similar symptoms, but the symptoms each individual patient has can help determine the type of leukemia. Any symptoms should be checked by a doctor.

The most common symptoms of leukemia are:

- Extreme fatigue that doesn’t respond to a good night sleep

- Enlarged lymph nodes that are swollen and tender as a result of leukemia cells building up

- Unexplained fever higher than 101 degrees that occurs frequently or lasts more than three weeks with no explanation

- Night sweats that can also occur during the day, and can drench the sheets through to the mattress

- Bruising and excess bleeding such as frequent nose bleeds caused by poor blood clotting which is also a symptom

- Poor blood clotting is apparent when small red or purple spots, called petechiae, appear

- Abdominal pain occurs when white blood cells accumulate in the liver or spleen

- Bone and joint pain usually occurs in the hips or sternum where there is a lot of bone marrow that is being crowded by abnormal cells

- Headaches and other neurological symptoms such as seizures, dizziness, visual changes, nausea, vomiting can occur due to leukemia cells in the fluid around the brain and spinal cord

- Unintentional weight loss of five percent or more of your body weight in 12 months or less. Weight loss can sometimes be a result of having a swollen liver or spleen which can lead to loss of appetite

- Frequent infections occur because white blood cells aren’t working properly to fight infections

- Anemia, or iron deficiency, occurs when there is a lack of hemoglobin in the blood to transport iron in the body. Iron deficiency can cause labored breathing and pale skin. Symptoms of anemia are nausea, fever, chills, night sweats, flu-like symptoms, weight loss, bone pain, and tiredness

Complications from Leukemia

Leukemia can cause several serious complications due to the nature of the disease and treatment. Complications such as life-threatening infections can occur when white blood cells are damaged or reduced. When white blood cells aren’t fully functioning, the body can’t properly fight infections, so any infections a leukemia patient gets, such as urinary tract infections or pneumonia, can become very serious. Low platelet counts make bleeding in areas such as the brain, the lungs, and the stomach or intestines very dangerous, while high white blood cell counts can cause leukemia cells to spill over from the blood into other organs possibly causing respiratory failure, stroke, or heart attack.

There are other complications that are related to specific types of leukemia. Notably, the development of secondary cancers and blood cancers are more likely in CLL patients. Another complication of CLL is called a Richter transformation in which the cells can transform into an aggressive form of lymphoma. Kidney failure can be a treatment-related complication of AML or ALL.

Leukemia Diagnosis

Leukemia can’t be diagnosed based solely on symptoms, but if leukemia is suspected, in a general exam, the doctor will look for an enlarged spleen or liver and take a blood sample. Further diagnostic testing may include a bone marrow test where a long needle is used to extract marrow from the center of a bone (usually the hip). The bone marrow test will help determine if the patient has leukemia and the type of leukemia.

Staging Leukemia

Staging is used to identify the size and location of cancer in the body. Typically cancers have four stages with Stage I usually indicating the cancer is in one location and is not very large. Stage IV indicates the cancer has grown large and spread far from the original location. Most leukemias aren’t usually staged because they are in the blood and therefore have already spread throughout the body. Instead, leukemia can be considered untreated, active, in remission, or recurrent. The exception is CLL, which can spread through the lymph nodes or the blood or bone marrow, so it does have three stages.

Treatment

The earlier treatment starts for leukemia, the better chance of remission. However, thanks to some exceptional advancements in leukemia treatment medications, doctors are often able to take the time they need to come up with the best treatment plan for each individual with leukemia, even in cases of acute leukemia if life-threatening complications are not present. When coming up with a treatment plan, doctors consider the patient’s age, overall health, and most importantly, the type of leukemia the patient has.

Leukemia treatment options vary for each type of cancer:

Watchful Waiting is used when treatment for slower growing leukemias, such as CLL, may not be necessary;

Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for AML, and sometimes a bone marrow transplant is needed;

Targeted therapies are medications that are tyrosine kinase inhibitors which target cancer cells, but don’t affect healthy cells. Targeted therapies have less side effects. Many CML patients have a gene mutation that responds very well to targeted therapy;

Interferon therapy is a drug that acts similar to a naturally occurring immune response which slows and then stops the leukemia cells. This therapy can cause severe side effects;

Radiation therapy is often used in ALL to kill bone marrow tissue before a transplant is done;

Surgery to remove the spleen may be necessary, depending on the type of leukemia;

Stem cell transplant is effective in treating CML and is usually more successful in younger patients. After chemotherapy or radiation or both are used to destroy the bone marrow, new stem cells are implanted into the bone marrow so noncancerous cells can grow.

Treatment for acute leukemia can take up to two years. It is usually done in phases. In the first phase the goal is to use chemotherapy for several weeks to kill the cancer cells and put the patient in remission. The second phase is designed to kill any remaining cancer cells using chemotherapy or stem cell transplant or both. The treatments and their side effects can be pretty harsh for older patients so researchers have been focusing on finding targeted therapies for acute leukemia, which have fewer side effects. Researchers are also hoping CAR T-cell therapy, which uses the patient’s own immune system to treat cancer, could be an eventual replacement for stem cell replacement therapy in older ALL patients. AML is more aggressive and often harder to treat, but several new targeted medications have been approved to treat AML. Researchers continue to look at other targeted therapy options and other drugs for AML.