“There’s something to be said for not being a patient,” one of my doctors said.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home.

I don’t miss shuffling from room to room or floor to floor and sitting in waiting rooms for hours. I love not needing to ask for rides or take cabs or public transportation while my white counts are low. I don’t miss being poked, prodded, weighed, and measured or having my vital signs documented in hallways while removing my coat, wig, and shoes. I love not having to roll up sleeves for the vials of blood to be drawn or to pull down my pants so the doctor can put a stethoscope to my belly and bowels.

Because of the increased health risks at hospitals, new access to telemedicine, and flexibility around clinical trial protocols, I can see my oncologist, face to face, through Zoom. Questions can be answered ,via email, a text, or a phone call. Clinical trial drugs are overnighted to me.

I enjoy the time and money I’m saving and the convenience of getting all care from home. But I also miss the real-life hugs, handshakes, and high fives that used to come with seeing the clinical team in person.

COVID Challenges

Many cancer patients are losing jobs, homes, loved ones, and health insurance. For those newly diagnosed with cancer, surgery, scans, and treatments must be done all alone. Those in active treatment are often terrified of catching COVID-19 while immunocompromised. Others are afraid hospital visits will expose our family members to COVID.

It’s startling how much hospital protocols and procedures have changed. When I look back or think about what comes next, I worry. I hope the pictures and stories below capture what it’s like to be an oncology patient and how swift and severe the COVID-related changes over the last few months have been and continue to be.

From Person to Patient

My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby.

My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby.

Eventually, we were called up and walked, single file, through halls by someone escorting us to the pre-op area. Each one of us was assigned a bed (pictured) and a nurse (not pictured). The photo is of the pre-op area.

My partner got to visit me before surgery. He was there when the surgeon, nurses, fellows, and anesthesiology came to prepare me for surgery.

If surgery were scheduled today, my partner wouldn’t be able to stay with me.

The Shock of a Post-Op Diagnosis

This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected.

This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected.

In the photo, I’m high as a kite and happy to be alive. I’ve just downed the iced coffee my partner snuck in (as planned and with permission from the nurse). In the photo, I am still in shock that my surgery was five hours long, it’s afternoon, and that cancer was found. I don’t yet know how serious my diagnosis will be. That will come twelve hours after surgery when the surgeon explains my cyst was actually a cantaloupe-sized cancerous tumor, aggressive, advanced, and usually chronic. Mercifully, my partner is with me as she explains that she had to do a total hysterectomy, removing ovaries, fallopian tubes, lymph nodes, and my omentum and lays out the timeline for chemotherapy.

My partner held my hand and crawled into my bed to hold me while I sobbed. But he provided far more than essential emotional support. He helped me stand and keep my balance, helped me get to my first trip to and from the restroom. He was there to advocate for me when I dozed off and to get the nurse when my call button went unanswered. He was the one who provided my loved ones with updates. He was the one who snuck my favorite health foods to help “wake up” my digestion enough to allow me to be discharged after one day.

It’s hard to imagine what that traumatic and challenging day would have been without him. I can’t imagine recovering from major surgery and receiving such devastating news alone but it’s what many diagnosed with cancer during COVID now endure.

At-Home Adjusting & Recovery:

Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.

Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.

Today, I’d either have had a telemedicine appointment or need to decide if an in-person visit with a medical professional is worth possible exposure to COVID. These are the types of decisions we are all facing but it’s especially scary when one is already vulnerable and fighting for life.

Early Treatment: Chemo Buddies are Not Optional

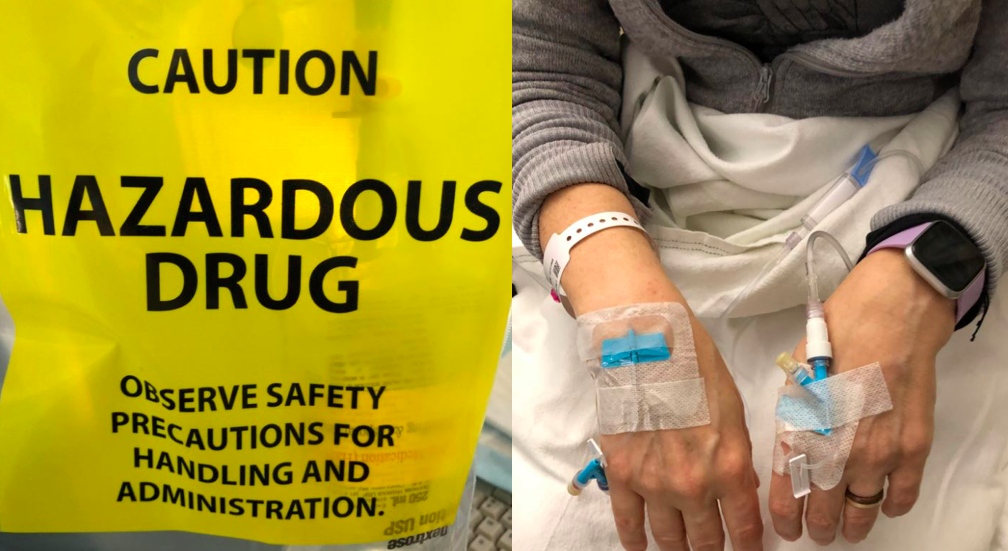

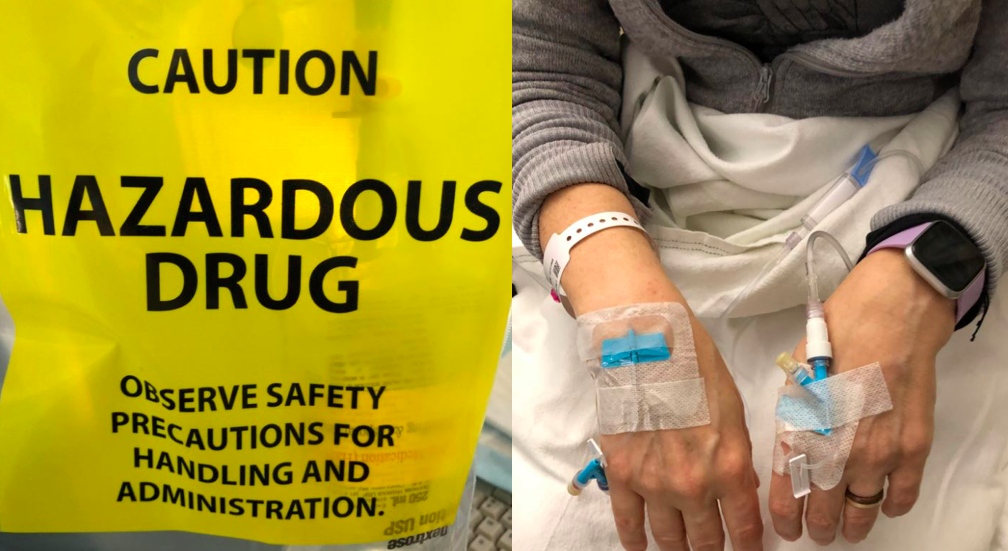

Getting chemotherapy infusions is time-consuming, scary, and intense. Everyone reacts differently to the many drugs given with chemotherapy (such as Benadryl, steroids, Pepcid, and anti nausea drugs). Everyone reacts differently to the chemotherapy, marked hazardous, that require the nurse to wear gloves, masks, and protective clothing to prevent contact in case of accidental spills. Some drugs make you sleepy, and parts of your body numb. Others make you feel amped, wired, and agitated.

Some cause nauseous, headaches, or allergic reactions, immediately and others not for days or weeks.

Having a chemo-buddy like Beth was a huge help. She was the one who asked for window seats in the infusion center, who made sure I got warm blankets. She massaged my feet and reminded me to listen to guided imagery. She sat with me in waiting rooms as we waited for my labs to come back to make sure my white and red blood counts weren’t too low, my liver counts not too high, and that the chemo was making my tumor marker scores go down.

She was the one who touched the elevator buttons for me, the one who walked me to the car and handed me off to my fiancé at the end of the day. She was the one who got me water, coffee, or snacks.

I felt safer whenever I had a chemo buddy with me and Beth would also take notes and make sure I didn’t skip any of my questions just because the oncologist seemed in a hurry.

Beth was not only a source of support but provided an extra pair of hands to plug in my iPhone, to hold my bags, food, or books. She was the person I could share tears, laughs, and heart to hearts with. She listened as I worried about my daughter, as I struggled to balance work and parenting.

She was there to support me as I talked endlessly about healthy eating, fasting, supplements, and complementary medicine. But the greatest comfort of all was knowing she would be there if passed out, fell, or had an allergic reaction to all the treatment drugs. At my last treatment, I was alone and Beth at home. It was hard.

In-Between Hospital Visits: Public Services & Personal Support

Social distancing during treatment is hard even for introverts like me who need a lot of alone time. When physically weak, short visits with loved ones who bring food, hugs, and gifts are life-affirming and life-changing.

Those who show up do so for cancer patients as well as our families. They help us to take care of our kids, partners, pets, plants, and housework. They help us manage as we face fear and loss, whether losing jobs or body parts, or hair and having few or no visits is hard. Today, barber shops where we might get our heads shaved are closed.

The wig shops and stores we go to for hats and head coverings are often closed.

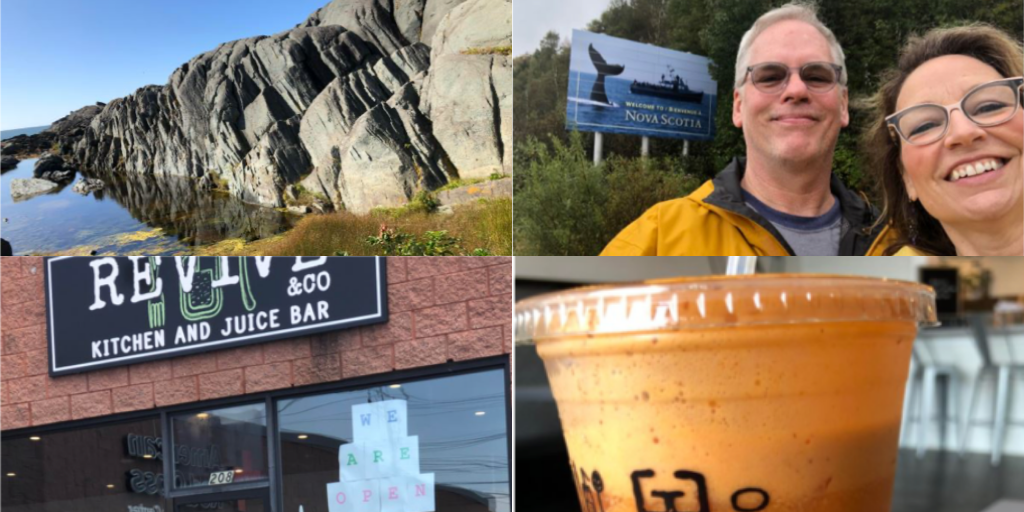

We can’t go out to eat with loved ones, or do yoga on good days. We can’t have parties for our loved ones to create normalcy or new rituals. We can no longer go out in the public either. We can’t do things such as sitting alone writing in a journal and drinking a smoothie when swallowing food is too hard.

We can’t travel to remind ourselves there is still beauty and magic in the world and to enjoy our loved ones and lives as much as possible.

These are not all small things or luxuries in coping with the brutal effects of cancer treatment and chemotherapy. They can change the cancer and recovery experience and all that helps keep us strong.

Later Treatment

We need others when we are sick. We might need help standing, walking, or eating. We might need rides, treatments, or blood or platelet transfusions. We might need help articulating symptoms and side effects. To have fewer in-person visits when so medically vulnerable can be anxiety-producing.

We also have less in-person celebrations with our clinical teams when we finish a line of chemotherapy or have a cancer-free scan. We no longer have informal pet therapy either with the cheerful and cuddly animals of friends, family, and neighbors.

I can’t imagine going to chemo alone, depleted, and with low white counts.

The increased risks, vulnerabilities, and lack of human company and tactile comforts feels indescribably epic.

Maintenance Treatment & Clinical Trials

My immunotherapy infusions (or placebo) have been put on hold for the past two cycles. I asked if I could remain in my clinical trial if I refused to come to the hospital for treatment until the risk of getting COVID is decreased. Luckily, I’ve been allowed to stay home. Clinical trial protocols, in general, are much more flexible as a result of the pandemic. My medication (or placebo pills) are mailed to me. Before March, in-person prescription filling was required and always took hours.

However, I’ve been weighing what I’ll do if I have to weigh virus-related risks against the possible benefits of clinical trial treatment. If I’m required to be treated at the hospital I may drop out of the trial. This is one of the many difficult decisions oncology patients often face but it’s made more complicated because of the coronavirus. .

Have Some Changes Been for the Good?

The losses, challenges, and changes are worrisome and real. That said, not all the COVID-related changes for oncology patients are bad. The whole world is wearing masks, staying home, socially distancing, and worrying about health, wellness, death, and dying.

Instead of being stared at when I wear a mask, I’m now in good company, because much of the world is doing the same. Many of us are consumed with health issues and worried about health, mortality, and immune functioning.

To be reminded, once again, that health and life aren’t guaranteed to anyone, that we are all facing mortality, and must appreciate every day we have, is strangely comforting. While I’m reminded of our collective vulnerability, to hear health concerns, risks, and challenges confronted as the world and nation’s collective concern is a reminder that none of us are being personally picked on for failing at being human, we are just, in the end, all excruciatingly fragile and mortal.

“I feel like I’ve been slow-dancing with death since last summer but now I feel less alone,” I told my friend Kathy. “It’s like others have joined you on the dance floor,” Kathy said. “Yes,” I said, which once again makes me feel like a person rather than a patient and there’s something to be said about not being a patient….

Resource Links:

- The National Cancer Institute guide: Coronavirus: What People with Cancer Should Know.

- American College of Surgeons: (ACS) Guidelines for Triage and Management of Elective Cancer Surgery Cases During the Acute and Recovery Phases of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic

- Sample of patient visitation changes hospitals have implemented from Mass General Hospital.

- Telehealth at Dana Farber.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Guidance for Conducting Clinical Trials

When not recovering or coping with her recent ovarian cancer diagnosis, chemo brain, and the other treatment-related side effects, Christine “Cissy” White works as Community Manager of the Parenting with ACEs community on ACEs Connection and blogs at www.healwritenow.com. White has been published in The Boston Globe, Spirituality and Health, Ms. Magazine, The Mighty, To Write Love on Her Arms, Elephant Journal, the Center for Health Journalism, and ACEs Too High. She is the 2019 recipient of the Touching Trauma at Its Heart Award, given by the Attachment Trauma Network for her work advocating on behalf of families coping with traumatic stress from developmental trauma. White has led Parenting with ACEs, Parenting After Trauma, and Writing to Heal workshops and speaks passionately about the need for first-person perspectives and the power of lived expertise. Her survivor-led advocacy has been written about in The Atlantic, Huffington Post, and The Mighty.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home. My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby.

My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby. This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected.

This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected. Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.

Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.