Metastatic Breast Cancer: Accessing the Best Treatment For YOU from Patient Empowerment Network on Vimeo.

How could genetic testing results impact your metastatic breast cancer treatment options? In this INSIST! Breast Cancer webinar, Dr. Julie Gralow discusses essential testing, the latest targeted therapies and emerging breast cancer research.

Dr. Julie Gralow is the Jill Bennett Endowed Professor of Breast Medical Oncology at the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

Download Program Resource Guide

Transcript:

Katherine:

Welcome to Insist Breast Cancer, a program focused on empowering patients to take an active role and insist on better care. Today, we’ll discuss the latest advances in metastatic breast cancer, including the role of genetic testing and how this may affect treatment options. I’m Katherine Banwell, your host for today’s program, and joining me is Dr. Julie Gralow. Welcome, Dr. Gralow. Would you introduce yourself?

Dr. Gralow:

Hi, thanks, Katherine. I’m Dr. Julie Gralow. I’m the Jill Bennett Endowed Professor of Breast Medical Oncology at the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

Katherine:

Excellent, thank you. Before we begin the discussion, a reminder that this program is not a substitute for seeking medical advice. Please refer to your own healthcare team. Well, Dr. Gralow, let’s start by helping people understand how breast cancer is staged. Could we go through those stages?

Dr. Gralow:

The staging of breast cancer has traditionally been by something we call anatomic staging, which has the tumor size, the number of local lymph nodes involved, and whether it has metastasized beyond the lymph nodes. So, that’s TNM – tumor, nodes, metastases. And so, that’s the classic staging, and based on combinations of those things, you can be a Stage 0 through Stage 4. Stage 0 is reserved for ductal carcinoma in situ, which is a noninvasive breast cancer that can’t generally spread beyond the breast, so that’s Stage 0, and then we go up for invasive cancer.

Interestingly, just a couple years ago, the big group that oversees the staging of cancers decided that in breast cancer, that TNM – the size, the lymph nodes, and the location beyond the lymph nodes – is not good enough anymore, so they came up with a proposal for what we call a clinical prognostic stage, which is a companion to the traditional TNM staging.

What they were getting at here was it’s not just how big your cancer is, how many lymph nodes, or whatever, it’s also at the biology of your cancer. So, this new clinical prognostic stage takes into account the estrogen and progesterone receptor of your cancer, the HER2 receptor at the grade, which is a degree of aggressiveness, and then, if your tumor qualifies, one of the newer genomic testing profiles that we use in earlier-stage breast cancer, such as the Oncotype DX 21-gene recurrence score or the MammaPrint 70-gene assay.

So, all of that goes into account now, and the whole point here is that the estrogen receptor, the HER2, the grade, and some of these genomics may actually make more difference than how many lymph nodes you have, where the cancer is, and how big it is, so it’s not just the size, but also the biology of the cancer that we’re trying to include in the new staging systems.

Katherine:

In this program, Dr. Gralow, we ’re focusing on metastatic breast cancer. Would you explain when breast cancer is considered to have metastasized?

Dr. Gralow:

That’s a great question because technically, if the lymph nodes in the armpit – the axillary area – are involved, that does represent spread beyond the breast, but if it stays in the local lymph node areas, it’s not technically called a metastatic or Stage 4 breast cancer. So, metastatic breast cancer would have traveled beyond the breast and those local lymph nodes, and some common sites would be to the bone, to the lungs, to the liver, less commonly – at least, up front – to the brain, and it could also travel to other lymph node groups beyond those just in the armpit and the local chest wall area as well.

Katherine:

What about subtypes? How are they determined?

Dr. Gralow:

The main way that we subtype breast cancer right now is based on the expression of estrogen and progesterone receptor, the two hormone receptors, and the HER2 receptor, the human epidermal growth factor receptor. So, to date, those are the most important features when we subtype, and so, a tumor can either express estrogen and progesterone receptor or not, and it can overexpress or amplify HER2 or not, and if you think that through, you can come up with four different major subtypes, in a way, based on estrogen receptor positive or negative and HER2 positive or negative.

When all three of those are negative, we call that triple negative breast cancer, and that’s about 18-20% of all breast cancers as diagnosed in the U.S. And then, when all three are positive, we sometimes call it triple positive, and the reason that we subtype is because we know that those different subsets act differently and that we have different drugs to treat them with, and we’ve got great drugs in the categories of hormone receptor positive and HER2 positive, and increasingly, some recently hope in a new drug approval or two in triple negative breast cancer as well.

Katherine:

For a patient to get diagnosed, what are the essential tests?

Dr. Gralow:

So, we’re talking about metastatic breast cancer here, and in the U.S., maybe up to 10% or slightly less of breast cancer is technically Stage 4 or metastatic at diagnosis. That means at the time we first found it in the breast, it had already spread beyond. So, an important thing that we’ll do with a newly diagnosed breast cancer is especially if there are a lot of lymph nodes are involved or the patient has symptoms that might say there’s something in the bone, liver, or lung is staging.

So, we’ll use scans – maybe a CAT scan, bone scan, or PET scan – and we will look at whether the disease has gone beyond the breast and the lymph nodes, and if so, where. So, maybe 8-10% of breast cancer diagnosed in the U.S. already has some evidence that it has spread beyond the breast, but the most common way that metastatic breast cancer happens is that a patient was diagnosed possibly years and years ago, treated in the early-stage setting, and now it comes back, and that is the most common presentation for metastatic breast cancer, and sometimes that can be due to symptoms.

As I said, if it comes back in the bone, maybe that’s bone pain. If it’s in the lung, it’s a cough. There are symptoms. Sometimes, it’s because we’ve done a blood test or something and we find some changes there.

And so, when a breast cancer has recurred, it’s really important to document that it’s really breast cancer coming back, first of all, and so, if we can, we generally want a biopsy, and we want to stick a needle in it if it’s safe to do, and look and verify that it looks like breast cancer, and also, it’s really important that we repeat all those receptors that we talked about from the beginning because it can change.

So, a cancer up front 10 years ago could have been positive for estrogen receptor, but the only cells that survived – mutated, changed – were estrogen receptor negative, so what comes back could be different. So, it’s really critical to get that biopsy, repeat the estrogen/progesterone receptor and HER2, and also, in an ideal world, now that it’s 2020 and we’re moving more toward genomics, to do a full genomic profile and look for other changes and mutations that could drive our therapeutic options.

So, staging, knowing where the cancer is, getting a good baseline by understanding where it is and how big it is so that we can follow it and hopefully see that it’s responding to treatment, and then, repeating all of the biology components so that we know what the best options are for treatment are really critical.

Katherine:

Right. How can patients advocate for a precise breast cancer diagnosis, and why is that important?

Dr. Gralow:

Well, all those things I just mentioned are key. Knowing exactly where it is so that we can monitor it – for example, if the cancer has come back in the bones, we would add what we call a bone modifying agent, a drug like zoledronic acid or denosumab – Zometa or – which can suppress bone destruction from the cancer, but if it’s not in the bone, we wouldn’t add that.

And, we want to have a good look everywhere so that we can see if it’s responding because sometimes, the tumor can respond differently in one area than another. Also, I think it’s really important to know what your treatment options are by doing that biopsy, getting a full panel, and looking at potentially hundreds of genes that could be mutated, deleted, or amplified so that we know what our treatment options are.

And, we’re not going to use all the treatment options up front, so it’s helpful for knowing that if this treatment doesn’t work or is too toxic, what are the second-line or third-line options? So, we make sure that there’s what we call good staging up front so we know where the cancer is, and then we make sure that we’ve looked at it as best we can in 2020 with all the genomics.

That would give us the best chance of being tailored – individualized – to the tumor. Sometimes, if we can’t biopsy it, like with a needle that would go into a liver spot, then increasingly, we’re looking at what we call liquid biopsies, and that can be drawing the blood and seeing if we can find parts of the tumor, whether it be the DNA or the RNA that’s floating around in the blood, and sometimes we can get that information out of the blood as well.

Katherine:

All right. Dr. Gralow, when you meet with patients, what are some of the more common misconceptions that you hear related to diagnosis?

Dr. Gralow:

Well, I think people do confuse – especially at an early diagnosis – that the metastases, the travel to the local lymph nodes, is not the same as a metastatic breast cancer, so we spend some time talking about how it’s still curable and not considered a distant metastasis if the lymph nodes are in the armpit or up above the collarbone, and so, that’s something that we spend some time talking about.

This whole term of “metastatic recurrence” – unfortunately, when you start looking online and get your information from Dr. Google, you read right away that it’s no longer curable, and in 2020, yes, that’s true. That’s probably the most specific statement that we can make. We are not going with curative intent, which means we treat for a defined amount of time, and then all the disease goes away, and we stop treatment, and then you go on with your life, and it never comes back. That would be cure.

But, I think it’s really important to point out that much of metastatic breast cancer can be highly treatable, and what we hope to do – and certainly, at least a subset of metastatic breast cancer – we want to convert it more to what we would call a chronic disease, and so, think of it more like hypertension, high blood pressure, or diabetes. These are diseases that we generally don’t cure with treatment, but that we can control with drug therapy, which sometimes has to be adjusted, and if we don’t control it, we can get some bad complications.

So, that’s not all metastatic breast cancer, unfortunately – we can’t convert all of it do something where we can use a therapy for a long time that keeps it in check and where you have a pretty good quality of life – but we’re hoping that more and more, we’re getting targeted therapies and more specific treatments to patients so that we can convert more patients to a more chronic kind of situation.

Katherine:

So, it’s something that patients live with.

Dr. Gralow:

Right.

Katherine:

Many people are confused about genetic testing. They often think that it relates to ancestry or physical traits like hair and eye color. What’s the role of genetic testing in breast cancer?

Dr. Gralow:

Well, you can do genetic testing of the patient’s inheritance, which is how most people think of genetic testing, and that’s actually really important and increasingly important in metastatic breast cancer to do your own inheritance. Have you inherited a gene that was associated with how your cancer developed? Because now, we actually have a class of drugs called PARP inhibitors that are approved for tumors that have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation with them. Most of those mutations were inherited, but not all. Sometimes they can develop as well.

So, now, when my patient – if she didn’t previously have genetic testing for an inherited risk for breast cancer either coming from mom or dad’s side of the family, a lot of people do have that up front, especially if they’re younger at diagnosis or they have a lot of family members with breast cancer. If she didn’t have that genetic testing done previously, at the time of the metastatic occurrence, I’m going to recommend that that be done because knowing if the cancer is associated with one of these DNA repair genes – BRCA1, BRCA2, some other genes – we have a new treatment option, which is an oral pill that actually is highly effective if the tumor has a mutation in one of these.

But, we can also – so, that’s genetic testing of the patient’s own DNA, but we can also do what we call genetic testing – or genomic testing, if you will – of the genes of the cancer. What were the changes in the DNA at the gene level that caused a normal breast cell over time to develop into a cancer cell that’s now growing without responding to our body’s checks and balances? So, what were those mutations, deletions, or amplifications in the tumor itself?

So, we’ve got the patient’s genetics, we’ve got the tumor’s genetics, and both of those come into play when we’re making our best treatment recommendations and trying to understand what the right approach is.

Katherine:

How is testing administered?

Dr. Gralow:

So, for our inherited testing, those gene changes can be found in every cell in the body, so we can do that from a simple blood test where we just look at the blood cells. We can actually do it with our sputum and with a cheek swab, even. You can get enough of the DNA from the inside of the mouth to do that.

For a tumor’s genetics, we need some of the tumor, so that’s either done with a biopsy into the metastatic site or, as I mentioned before, increasingly, we’re exploring the potential for a liquid biopsy – so, drawing some blood and then trying to find pieces of the tumor that are shed into the blood.

Katherine:

What advances have there been in testing?

Dr. Gralow:

Well, it used to be – just going back a couple of years ago – that we didn’t do a lot of this genetic testing or genomic profiling of the tumor because we didn’t have many – the term is an “actionable mutation.” So, if we found something, would we do something with it? Did we have a drug we could use to do it? But, more and more and more, even in breast cancer, we’re finding actionable mutations that would drive therapy.

For example, in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer, we have a new class of targeted therapies called PI 3-kinase inhibitors – a drug called alpelisib or Piqray was approved in the last couple of years in that category – and it only is effective in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer that has a mutation in the PI 3-kinase gene. So, that would be something we’re looking for in the tumor’s genes, and actually, we need to know that there’s a mutation to even get the drug approved for treatment because it doesn’t work if you don’t have that mutation.

Increasingly, we’re finding some changes that can happen in the estrogen receptor gene and the HER2 gene, interestingly, so that you can have estrogen receptor expressed on your tumor, but over time, that tumor might develop an estrogen receptor mutation so that it stops responding to certain drugs that target the estrogen receptor.

And so, that’s called an ESR1. That’s the name of the estrogen receptor gene – an ESR1 mutation – and that would tell me probably not going to respond as well to a drug in the class we call aromatase inhibitors, but might respond better to a drug in the class that we call the selective estrogen receptor degraders like fulvestrant or Faslodex, is the name of a drug in that class.

We’re also finding that you can have what we call activating mutations in HER2, and they can be present whether the tumor overexpresses HER2 or not, and we’ve got some ongoing clinical trials looking at if the tumor doesn’t have extra HER2 on its surface – so, it doesn’t have extra HER2 protein, but at the gene level, it’s got an activated HER2 gene – we can use certain types of HER2 therapy to treat it, and we’re testing that right now in clinical trials.

So, could we even use some HER2 drugs even though technically, the tumor would be classified as HER2 negative? So, fascinating increasing information that we’re understanding, and I also mentioned before we can inherit mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and 2, but fascinatingly, the tumor can acquire those mutations. Even if we didn’t inherit a mutation, we can see mutations in the BRCA1 and 2 gene – we call those somatic as opposed to germline mutations. So, “germline” means it’s in every cell in your body, but “somatic” means the tumor somehow acquired this over time.

And so, we’ve done – we just presented some very early results of a trial, and we’re expanding this trial, looking at if you didn’t inherit a BRCA1 or 2 mutation, so technically, you don’t qualify for a PARP inhibitor, but if the tumor acquired a mutation and we can prove that with testing the tumor’s DNA, then we have seen responses from these PARP inhibitors, so that opens up another whole class of treatments, and there are other DNA repair genes that actually may be qualified as well that we can inherit or that can be acquired by the tumor.

So, more and more, we’re doing this genomic profiling, and it is leading to results that would give us possible treatment options.

Katherine:

Dr. Gralow, the goal of this program is to provide the confidence and tool for patients to advocate for the essential tests to get best care personalized to them. Are there specific tests that patients should make sure they have?

Dr. Gralow:

Well, there are a lot of assays out there to do this genomic profiling or genetic testing of the tumor, so I don’t promote any one. Various institutions do it and do it well, various companies do it, but I think every metastatic patient should have the tumor looked at in this kind of profiling.

I also think every metastatic patient should advocate for having a biopsy of their cancer, and if a biopsy cannot be done safely in the recurrence, then see if they could get a liquid biopsy – have blood drawn to find it. So, I think that patients should be asking about this. Sometimes, insurance won’t always cover it, and so, my job as a treating physician is to advocate for that, to do an appeal.

More and more, because we have so many actionable mutations in breast cancer now, I’m not having insurance decline, but occasionally, it does, and then it’s our job as the healthcare providers to make the case that yes, this will impact the patient, and yes, it should be covered by insurance.

Katherine:

You’ve been referring to a number of terms. Patients may have heard the BRCA or “braca” that relate to breast cancer in genetics. Would you give us an overview of common mutations in breast cancer?

Dr. Gralow:

So, of the mutations that we can inherit, the first two that were discovered were BRCA1 and BRCA2, and for all breast cancer – not just metastatic, but all breast cancer – we think that maybe 5-10% of breast cancer is the direct result of the inheritance of a strong gene that gives you a high – not 100%, but a high likelihood of developing breast cancer.

So, for BRCA1 and 2, these two genes are associated predominantly with breast and ovarian cancer, and if you live out your normal lifespan, you could have up to a 75-80% chance of getting one of those two cancers, and breast cancer being more common. Also, some association with some other cancers including, interestingly, prostate cancer, which we’re learning more about.

So, BRCA1 and 2 are the most common, and they tend to be found – because they have such a high association with the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, they tend to be found in families that have a lot of other breast cancers, and also breast and ovarian cancer presenting at a younger age. So, you’ve inherited a gene that leads to a high predisposition, and the cancer occurs earlier.

So, whereas the average age of diagnosis of breast cancer in the U.S. is 61-62 most commonly, in a patient who’s inherited a BRCA1 or 2 gene mutation, it’s closer to 40-42 – so, a lot younger. And then, there are a variety of other genes that can be inherited that are either much less common or have a weaker link. So, for example, there are genes called CHEK2 or PALB2, ATM, P53 – I just mention that because some of the listeners will potentially have one of those mutations or have heard it. Those are either rarer or they’re associated with a weaker chance of getting cancer.

So, those might be more commonly found in a family that doesn’t have a lot of cancer in it because a carrier – the mother or the father – and their other relatives would have maybe only a 30% chance of getting breast cancer in some cases. So, there would be a lot of carriers who don’t get cancer.

So, as I mentioned earlier, I think it’s really important – especially right now in metastatic breast cancer – that pretty much everybody, even if you didn’t have a strong family history, even if you weren’t diagnosed at a young age, get tested because if we find one of these inherited mutations, we now have some additional treatment options, especially right now, approved for BRCA1 or 2, but clinical trials going on for many of these other genes.

Katherine:

How do these mutations affect disease progression and prognosis?

Dr. Gralow:

So, most of the genes I’ve mentioned – in their normal state, they’re critical, actually. They’re called DNA repair genes, and their job in our life is when we accidentally make a mistake when we’re replicating our DNA and two cells are dividing, if there’s a mistake in the DNA, they go in and repair it. And, we’ve got all kinds of mechanisms to try to prevent mutations from happening as cells divide, and BRCA1 and 2 are a key part of that, and so, they’re fixing it.

So, if you inherit a mutation in one of those genes, you still have some ability to repair any routine mistakes that are being made, but over time, you have less ability, and then, if you get a cancer that has a deficiency in BRCA1 or 2, those cancers can be more sensitive to certain kinds of chemotherapy that affects DNA repair.

So, for example a class of chemotherapy agents called the platinum drugs – carboplatin and cisplatin – may be more effective in BRCA1- or 2-mutated cancers, also more generally in triple negative breast cancer because they can be more similar to BRCA1-mutated cancers in a lot of ways.

So, to go back to your original question, once a cancer has developed in a patient who has a BRCA1 or 2 mutation, we treat that cancer for what it is. So, it might have developed estrogen – have estrogen receptor on the surface or HER2, so we treat it as the subtype that developed, and actually, the chance of cure is just the same for BRCA1-associated breast cancer as it would be for one that doesn’t have a BRCA.

But, the chance of getting a second breast cancer – a totally new breast cancer – would be higher unless you chose to remove both of your breasts and the bulk of your breast tissue. So, decisions like surgery – if you had a known BRCA1 mutation, we’d treat the cancer you have now aggressively and for cure, but when you talk about your surgery options, we’d say doing more aggressive surgery, like removing both of your breasts – that’s not gonna improve your chance of surviving the cancer you have now, but it will markedly reduce the chance of getting a second breast cancer.

So, you could consider that as an option for surgery – not to improve your chance of this cancer, but to reduce the chance of another breast cancer. So, your surgery decisions might be impacted by knowing your BRCA1 or 2 mutation. And then, clearly, if you had metastatic breast cancer, knowing if you had the option of a PARP inhibitor, one of the drugs in that class could be – you could have a different treatment option for drug therapy.

Katherine:

Well, Dr. Gralow, what other factors should be taken into consideration with a treatment route?

Dr. Gralow:

I always like to think of the treatment decision as relying on three factors, and the first relates to the tumor factor, the cancer factor.

So, we talked a lot about the biology, the estrogen receptor, the HER2, the genomic profiling. So, that’s critical, but there are two other components that we need to really strongly consider when trying to devise the right treatment regimen. One of those is patient factors, and not just the patient’s genetics, but are they pre- or post-menopausal?

What is the age? Where are they in life? Are they young with young kids? Are they working, and is that an important priority for them? Are they older and with grandchildren, and they don’t need to work? What is it that would be critical? What are the patient’s priorities here, and what are their fears, what are the things they would – what would be really important as we plan a regimen? And so, the patient factors which would be patient priorities and where they are in life right now.

And then, there’s factors related to the treatment itself, which would include not just how effective it is, but – and, this is really important when trying to decide regimens – what are the side effects of a regimen? For some patients, hair loss is a big deal, and we can put it off as long as possible – maybe choosing the first couple regimens don’t cause hair loss sometimes.

But, for other people, that doesn’t matter to them. For some, we have oral – some regimens, and that could keep them out of the infusion room, and others actually – I’ve had patients who actually like coming into the infusion room regularly so that they can review the side effects and get the reassurance provided by it. So, we’ve got different route of administration of the drugs, different side effects. If you already had, for example, a neuropathy – a numbness/tingling of fingers and toes – from treatment that you might have gotten for early-stage disease, we’d probably want to avoid drugs where that’s their major side effect in the metastatic setting and that would increase that even further.

We’ve got some drugs that cause a lot of toxicity to our GI system – nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea – and other drugs that don’t. And so, understanding what symptoms the patient already has and actually tailoring the treatment based on some of the side effects of the drug could also be done, as well as how they’re administered. So, again, patient factors, tumor factors, and then, factors related to the treatment itself all come into play when we make decisions.

Katherine:

There have been so many advances in breast cancer research. What are you excited about in research right now?

Dr. Gralow:

Well, every single drug that’s been approved, every single new regimen that’s been approved in breast cancer is the direct result of clinical trials, and this is a major part of my career, is to help patients get access to clinical trials and run important clinical trials that could lead to new discoveries – is this regimen better? What’s the toxicity?

Because until we have a cure for breast cancer, we need to do better, and we need to research better treatment options. So, doing trials, having access to clinical trials where you can participate, help move the science forward is key.

I think where we’re moving with breast cancer is the more we’re understanding the patient and the tumor, the more we’re realizing every single breast cancer is different, actually, and whereas when I started my training 20-plus years ago, breast cancer was breast cancer – we weren’t even using HER2 yet, we were just learning how to use estrogen receptor, and we kind of treated everything the same – now, we’re subsetting, and subsetting, and subsetting. Even in triple negative breast cancer now, which is about 18-20% of breast cancer, we’re subsetting.

Does that triple negative breast cancer have PD-L1, which is associated with being able to get immunotherapy drugs? Does it express androgen receptor? Because sometimes, even a breast cancer that doesn’t have estrogen or progesterone receptor can express the androgen receptor, like prostate cancer, and we can use some prostate cancer drugs. So, even triple negative breast cancer we’re subsetting and subsetting, and could that triple negative breast cancer be associated with a BRCA1 or 2 mutation, and then we can use the PARP inhibitors?

So, I’m actually really excited about that we’re learning more and more, and subsetting, and not treating breast cancer as one size fits all, and if we can better tailor the treatments to the patient and the tumor, that we are going to get to the point where I can tell my patients yes, we can get cures in metastatic breast cancer.

Katherine:

For patients who may be hesitant to speak up – to advocate for themselves in the process – I’m gonna start again. For patients who may be hesitant to speak out for themselves and advocate for their own care and treatment, what advice do you have?

Dr. Gralow:

You have a whole team who’s behind you, and I’m the MD on the team, but I’ve got a nurse practitioner, and a nurse, and a scheduler, and a social worker, and a nutritionist, and a physical therapy team, and financial counselors. I’ve got a whole team who works with me. And so, a patient might be hesitant to speak up during the actual appointment with their physician. It’s a short amount of time. I would recommend come into it with written-down questions because things go fast. You don’t get a lot of time with your doctor.

Things go fast, but don’t come in with 25 questions, either. Pick your top few that you want to get taken care of this visit because if you come in with 25 or 30, you’re gonna lose the answers to most of them. Maybe bring somebody with you who’s an advocate and a listener for you who could be taking notes, so you can process and you don’t have to write it down, or ask if you can record it. It’s really important if you’re newly diagnosed or maybe there’s a progression and you’re going on a new treatment. That’s okay too.

But, I would also say you have a whole team behind you, so sometimes, if you don’t have time or if you’re hesitant to speak up in your doctor’s visit, you can ask the nurse, or maybe you can ask the social worker for help, even. See if there’s support groups around.

Interestingly, we’ve got a peer-to-peer network where patients can request to talk to somebody else who’s matched to them by some tumor features, and their stage, and things like that. Maybe finding somebody else who’s gone through something similar, and somebody independent to talk to instead of relying on your family.

It can also be really helpful to talk to a therapist or a psychologist about your fears, and sometimes, you want to be strong for your family, strong for your children and all, but you need a safe space with somebody that you can just express your fears and your anger if that’s what’s going on, or your depression or anxiety to while you’re trying to hold a strong face for others in your family. So, I would encourage patients to look at who is the whole team and talk to the other members of the team as well, and sometimes, they can help advocate.

Also, find somebody who might be able to come to your appointments with you, somebody who will help you advocate or remind you – “Didn’t you want to ask this question?” – or be another set of ears that you can process it with afterwards.

Katherine:

Dr. Gralow, we’ve covered a lot of useful information today for patients. Thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Gralow:

Thank you, Katherine.

Katherine:

And, thank you to all of our partners. To learn more about breast cancer and to access tools to help you become a proactive patient, visit powerfulpatients.org. I’m Katherine Banwell.

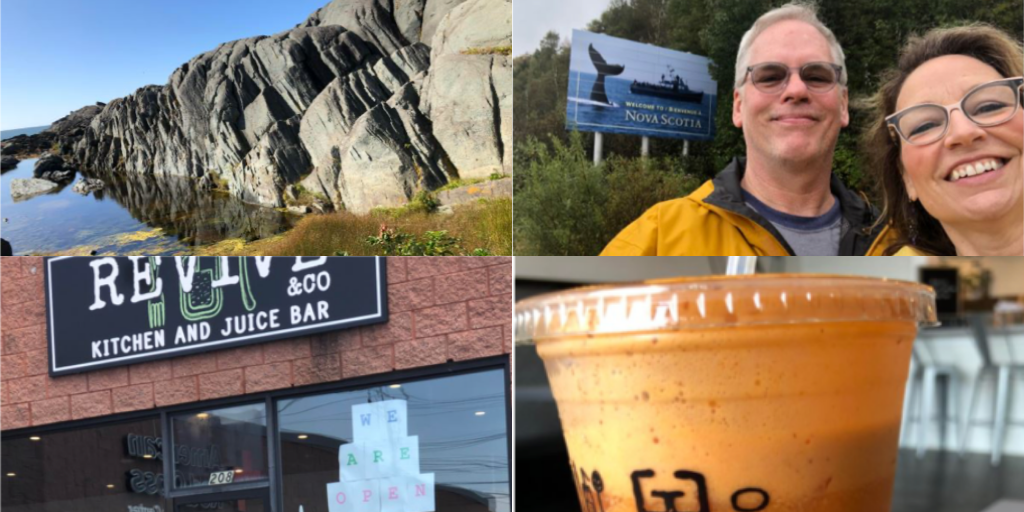

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home. My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby.

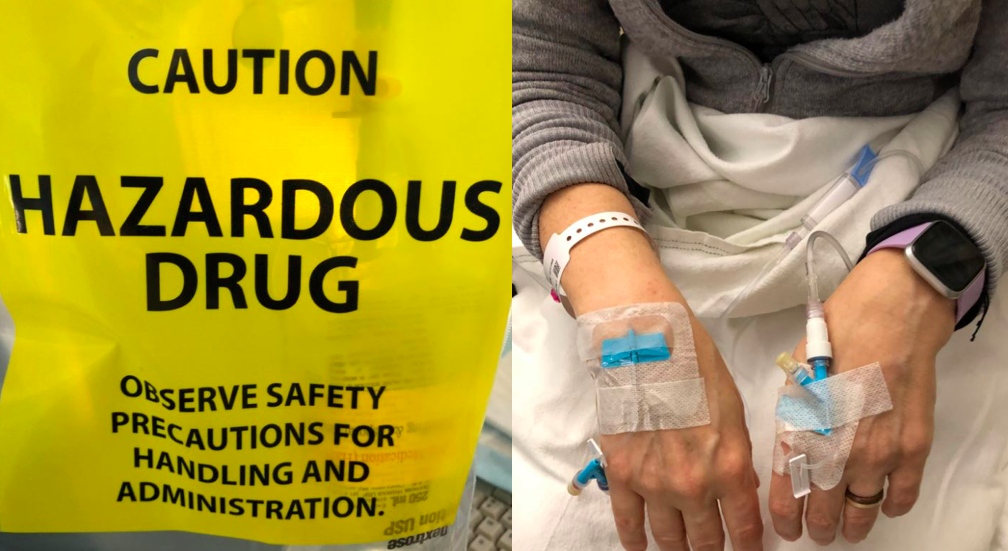

My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby. This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected.

This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected. Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.

Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.