“Is there a pressure to be positive all the time?” my friend Kathy asked.

It’s a good question. I said, “No,” and then “Yes,” and added in a “Maybe.”

But it’s not a simple yes, no, or maybe. It’s actually Yes-No-Maybe all at the same time. My kid is on Facebook and so is my family. My friends are on Facebook and they want the best or at least to know I’m not suffering. I’m aware of that and of them. But that doesn’t mean I show up fake or put on fronts. I don’t.

The pressure to be positive isn’t external. I am safe to be real with SO MANY people and that luxury is a gift beyond measure. The desire to be positive comes from within but it’s not motivated by pressure. It’s real. In general, I ACTUALLY FEEL positive.

And also, when my oncologist asks how my partner or daughter are doing, I say:

“Well, I’m cranky, lethargic, have chemo-brain, and obsessed with recurrence so that’s fun for them…”

That’s also real.

Real is positive.

So, when people say I’m strong, a rock star, a warrior, and a fighter, I can’t say I feel I am any of those things. My day to day to life has been changed and though I feel 100% half-ass as a mom, partner, friend, relative, and employee – I also know I’m doing the best I can.

I don’t even have much time to think of how I’m doing because I’m so busy doing, if that makes sense.

It’s like I woke up after surgery standing in the middle of a highway I didn’t drive myself on. The focus is dodging the cars going 75 m.p.h. on my left and right while feeling groggy and confused. When I manage to make it to the sidewalk or the rest area, the relief I feel is real. I’m happy to be alive and out of danger. It’s a genuine and consuming experience. I’m relieved any time I’m not in the road and also aware I could be dropped back on that highway in another minute, day, week, or year.

That’s the complexity and reality of living with cancer (#ovarian, high-grade serious, stage 3) that, even when it’s effectively treated, still recurs 75% to 85% of the time. To have no evidence of disease isn’t the type of blessing I’ve been in the habit of counting.

For decades, I have had the luxury of physical wellness and had never stayed overnight in a hospital. Health isn’t something I take for granted anymore but that doesn’t make me a warrior as much as it makes me someone changed by cancer more than by choice.

I used to think people were sick with cancer, and either mounted a “successful” fight and returned to living or lost “the fight” and died. It seemed either/or and as those were the two extreme outcomes.

I knew my mother HAD cervical cancer in her early 20’s and survived. I knew that my Nana and her two siblings had cancer in their 60’s, and did not. They died.

I know cancer is always a full-on fight for the person with cancer and those that live with and love them (us), but fights are won or lost and that is the problem with the “fight cancer” narrative. It’s way too simplistic for the complexity of cancer, cancer treatment, cancer survivorship, palliative care, and grief.

It omits the vast amounts of time that many of us live with cancer. We live with it in active form, or in remission, or in fear of recurrence, and sometimes with recurrence after recurrence. That way of living may last one or two years or one or two decades. We may have years we seem to be “winning” the fight and years we seem to be “losing.”

But winning and losing is far too simplistic. Some live and have loss. Some die and should be counted as winners.

I’d never known some fight the same cancer repeatedly, or “beat” it before getting another kind and another and another. I didn’t know that people cancer can be a lifelong disease and that some kinds are genetic time bombs in our bodies and families that can put us at risk even if we never smoked.

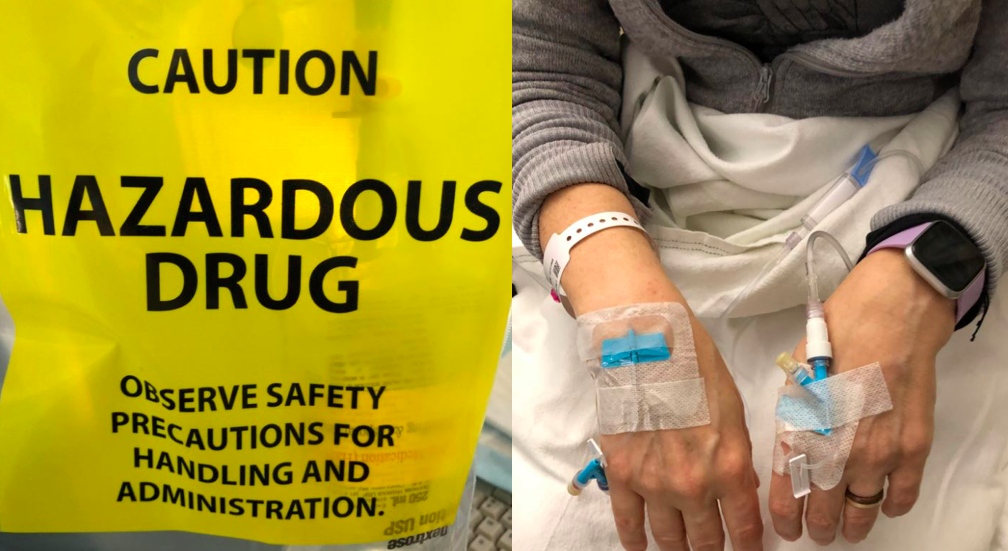

I didn’t know that one can have or five surgeries, that the side effects can start at the head (loss of hair, headaches, chemo brain, no nose hair, dry mouth, hearing loss), for example, and go all the way to the feet with lymph edema, joint pain, neuropathy, and that all the organs in between can be impacted as well.

I didn’t know that most cancer side effects are not from cancer but the treatments to fight, eradicate, and prevent more cancer.

I didn’t know that in addition to chemo, one might contend with liver or kidney issues, with high or low blood pressure, with changes to the way heart beats, the digestive symptom works.

I didn’t know that cancer surgery might include a hysterectomy and removing some or several organs, lymph nodes and body parts I’d never heard of. I didn’t know how it’s impossible to know what is from cancer, chemo, menopause or the piles of pills one is prescribed.

I didn’t know how much the body can endure and still keep going. I didn’t know I’d have a body that would have to learn and know all that I was mostly ignorant about -even though cancer is a disease not unknown to my own family members.

I am still learning and knowing and going. I hope what I learn keeps others from having to have first-hand knowledge of the cancer experience.

And even as I say that I know the ways I’ve been changed are not all bad, hard, or grueling.

I didn’t know that at, even in the midst of being consumed by all things basic bodily functioning (breathing, heart beating, eating, pooping, sleeping, and staying alive), one can also be grateful, satisfied, and appreciate life and loved ones.

I know it now and feel grateful daily.

Five months after my diagnosis, I’m what’s called NED (No Evident Disease). It means that after surgery, and then 5 rounds of chemo, a carbo/taxol combination every 3 weeks, there is no sign of ovarian cancer. My CA 125, a cancer marker in the blood, is back to normal. Things are looking better today and I’m grateful, optimistic, relieved, but also know that my life is forever changed, and I’ll never be out of the woods.

Despite my NED status, my chances of being alive in 10 years are 15%.

Despite my NED status, my chances of being alive in five years are less than 30%.

Did you know 70% of those with ovarian cancer die within five years of being diagnosed?

I’m not a statistic, but a person – still, it’s hard not to do the calculations.

5 years from my diagnosis I’ll be 57, and my daughter 21.

5 years from my diagnosis, my partner will be 62.

Will we get to retire together, ever? Will I get 5 years?

It’s hard not to wonder if some or all of those five years are what most would consider “good” years and how I will manage well no matter what? And how my loved ones will fare…

So I focus on moments, days, and now.

My new mantra remains, “In this moment….”

It’s how I approach all of my days.

I do think and worry about the future, and even plan for the worst while also planning for the best. Because the best is always possible.

What if, I’m the 15% and live for 10 or more years? What if I make it to 62? What if a new way to detect, manage, or treat ovarian cancer is discovered? What if I discover some synergy in remedies and medicines not yet combined?

Maybe I will see my kid graduate college or start a career. Maybe I’ll help her shop for furniture in a new apartment. No one knows the future. No one guaranteed more than now.

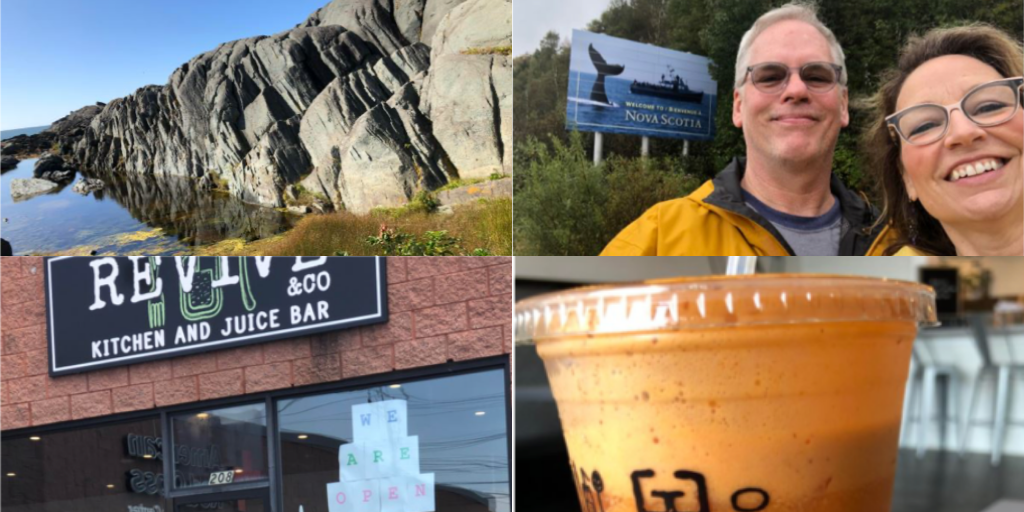

Maybe I’ll get to go to Europe with my partner, elope and return married, or stay forever engaged.

Maybe I’ll attend a mother-daughter yoga retreat with friends like I’ve always wanted to do.

Maybe I’ll spend a month at a cabin writing and eating good food with my besties?

Maybe I’ll be able to be there for my family members and friends the way they have been there for me?

Maybe I’ll get to walk my dog at the same beach and park, with my guy, my brother and sister-in-law, and our dogs and kids?

I don’t know how much time I’ll get or what life holds.

I know when my Nana died in her mid 60’s it seemed way too soon. I know that now, if I make it to my mid 60’s, it will be miraculous.

I don’t put as much into my retirement savings.

I think more about how to spend time, and money, now.

These are not negative thoughts they are the thoughts of someone contending with cancer and wide awake while pondering my own mortality.

“You won’t die of this,” some have said. “Cancer won’t kill you.”

But no one knows that for sure. It’s not an assurance the oncologists offer.

People mean well when they say such things but I no longer bite my tongue when I hear these words.

I say, “I might die of this,” (and I think, but don’t say, and you may as well).

I do remind people that we are all going to die and few of us will get to choose the time or place or method. It’s not wrong to acknowledge mortality. It’s not depressing and it does not mean one is giving up. I want to be responsible, and quickly, as I don’t have the luxury to be as reflective as I used to be because cancer is all-consuming.

I’ve barely had a moment to reflect on the past five months never mind the last five decades. I am trying to stay on top of the bare minimum requirements of being alive. I can’t yet keep up with emails or phone calls or visits. Projects and goals and plans of all kinds have shifted, paused, halted, or been abandoned.

My energy is now a resource I have to monitor and preserve. My will is not something I can endlessly tap into or call upon to motor me and keep me motivated. There’s no resource I have yet to tap into or call upon. Each day, I must consciously and repeatedly work to fill the well. And now, when friends and family who work while sick, I no longer think they are tough or strong. I think of how we routinely punish and ignore our bodies. I notice how often we run on fumes, require more of ourselves than we have as though we will never tire out.

I think of all those who must or feel they must keep going no matter what, without pause or rest, oblivious to the toll it will take or of those who have systems that can’t fight their germs. And I think of employers who sometimes require it because they offer no paid time off.

I used to run myself ragged. I used to say, “I’m digging deep, into my bone marrow if I have to.” I wasn’t being literal.

Now, when my iron and my platelets go low, I think of my old words in new ways. Now, even my bone marrow isn’t what is used to be.

I’m entirely who I always was and completely different.

It’s both.

I am more and less of who I was.

My life and days are simple and structured now and also heavy, layered, and complex. Who and what fills my day, by choice and not by choice, is radically different.

Cancer changed my life. That’s irrefutable and will be whether I live or die in the sooner or in the later.

I speak with and interact with doctors, nurses, life insurance and disability insurance and pharmacists more. I spend more money on supplements, clean eating, and make more time to walk, exercise, and sleep. There’s so much less I am capable of.

But sometimes, even without hair, I feel totally like myself.

Sometimes, like this week, my daughter caught me in the middle of life, reading a book, petting the cat, on my bed in my heated infrared sauna blanket. I was relaxed and at ease.

I shared this photo and someone commented on how my “cat scan” was quite feline, – the image brought a whole new meaning to the “cat scan” image.

I laughed and laughed and laughed. I’m still laughing.

In this moment, in many moments, I’m humbled by the enormity of all things cancer and being alive. That’s real. That’s there. It can be intense.

But also, in this moment, I’m laughing.

And laughing, it turns out, is my favorite way to live.

When not recovering or coping with her recent ovarian cancer diagnosis, chemo brain, and the other treatment-related side effects, Christine “Cissy” White works as Community Manager of the Parenting with ACEs community on ACEs Connection and blogs at www.healwritenow.com. White has been published in The Boston Globe, Spirituality and Health, Ms. Magazine, The Mighty, To Write Love on Her Arms, Elephant Journal, the Center for Health Journalism, and ACEs Too High. She is the 2019 recipient of the Touching Trauma at Its Heart Award, given by the Attachment Trauma Network for her work advocating on behalf of families coping with traumatic stress from developmental trauma. White has led Parenting with ACEs, Parenting After Trauma, and Writing to Heal workshops and speaks passionately about the need for first-person perspectives and the power of lived expertise. Her survivor-led advocacy has been written about in The Atlantic, Huffington Post, and The Mighty.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home.

“It feels so good,” I said during our telemedicine appointment, “to be away from the hospital for eight weeks in a row.” It’s the longest hospital break I’ve had since being diagnosed with cancer last summer. Before mid-March, I’d been to four to ten medical appointments every month. Being a cancer patient felt like a full or half time job. Because of the pandemic, I’m now treated by my oncology team from the comfort of my own home. My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby.

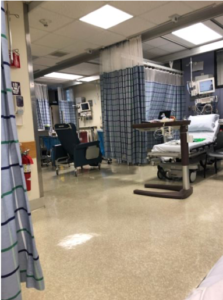

My partner drove me to the hospital on the morning of my surgery. We checked in before 6a.m. and waited, with others, in the lobby. This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected.

This is me in post-op. My partner took this photo on his phone and was able to share it with my family and friends to let them know I made it through surgery. They were worried because it went hours longer than expected. Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.

Going home after surgery is comforting and scary. My right leg was giving out from under me because my obturator nerve “got heat” during my surgery. I had trouble standing in the shower or lifting my right leg onto the bed or into a car. I had extensive swelling and bruising on my right side and pelvic area and had a bit of a reaction to the bandage tape. I didn’t know what was normal. And after a phone call to the hospital, I was asked to come back in for a check-up.